We remember a lot of aviation pioneers for their firsts. The first to fly in an aircraft? Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier in 1783, in a balloon designed with his brother Joseph-Michel. The first to fly in a glider? George Cayley’s coachman in 1853, though he flew under protest. The first to fly a powered, heavier-than-air craft in a series of controlled and repeatable flights? Orville and Wilbur Wright, in 1903.

We know that people have wanted to fly probably as long as they’ve been able to look up.

“The desire to fly is an idea handed down to us by our ancestors,” Wilbur once wrote, “who, in their grueling travels across trackless lands in prehistoric times, looked enviously on the birds soaring freely through space, at full speed, above all obstacles, on the infinite highway of the air.”

But who actually tried it first?

History suggests that it may well have been a man named Bladud, a British prince who lived around 850 B.C. Bladud may have been a myth, possibly never existing at all, which is why history only “suggests” in this case — that’s what history does when it doesn’t feel too sure of itself.

As a young man, or so the story goes, Bladud was banished to the village of Swainswick in Somerset after having the impertinence to contract leprosy while in Greece. Resigned to life as a humble pig farmer, one day Bladud noticed that his pigs, after wallowing in the mud of a natural hot spring in the area, were seemingly cured of all manner of skin conditions. With little to lose, Bladud jumped in, wallowed about, and his leprosy was cured soon thereafter; he returned to the kingdom in triumphant good health.

When Bladud’s father, King Rud Hud Hudibras, died, Bladud, having been back in good standing for some time, inherited the throne. During his reign, he founded the city of Bath, based around the hot springs that cured him, and that he subsequently claimed he’d created through the use of magic. Bladud was, perhaps, neither the most rational nor the most honest of monarchs, fictional or otherwise, but he did have one thing in common with many of us: he wanted to fly.

Somewhere around 852 B.C., perhaps guided by his increasing interest in necromancy, a type of magic that involves communicating with the dead, Bladud decided to try it. He built some wings out of feathers, and launched from, or at, depending on which version of the legend, if any, that you believe, the Temple of Apollo in what is now London.

Somewhere around 852 B.C., perhaps guided by his increasing interest in necromancy, a type of magic that involves communicating with the dead, Bladud decided to try it. He built some wings out of feathers, and launched from, or at, depending on which version of the legend, if any, that you believe, the Temple of Apollo in what is now London.

If Bladud had somehow been able to wait 2,834 years before making his attempt, he would have found some sound advice in the book Life, the Universe, and Everything, by the late Douglas Adams.

“There is an art,” Adams wrote, “or rather, a knack to flying. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss. Most people fail to miss the ground, and if they are really trying properly, the likelihood is that they will fail to miss it fairly hard.”

King Bladud, prince-turned-swineherd-turned-magician-and-monarch, failed to miss the ground very hard.

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s book The History of the Kings of Britain, Bladud “tried to fly through the upper air … came down … and was dashed into countless fragments.”

We know now, of course, that building wings out of feathers and strapping them to your back just won’t work. But, back in 852 B.C., it certainly could have seemed plausible, especially to a self-styled magician who believed he could talk to the dead. Regardless, Bladud died, possibly but not probably aviation’s first casualty. Incidentally, he was succeeded by his son, another potentially mythological man that Shakespeare later made famous in his tragedy, King Lear.

Some scholars posit that Bladud might have existed, but that the whole story of him attempting to fly was just a case of Geoffrey borrowing the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, which came along 700 years later. Regardless, Bladud wasn’t the first to want to fly, and almost certainly wasn’t the first to try, but, chronologically, he’s the first that I’m aware of that anyone claimed had actually tried. Unless you count the Chinese Emperor Shun who, in 2,200 B.C., allegedly leapt from a burning tower and wafted gently to the ground thanks to a really big hat. If anything, he may have been history’s first skydiver, but that’s another story for another time.

Bladud may or may not have ever lived, and if he did, he may or may not have died trying to fly.

None of that really matters.

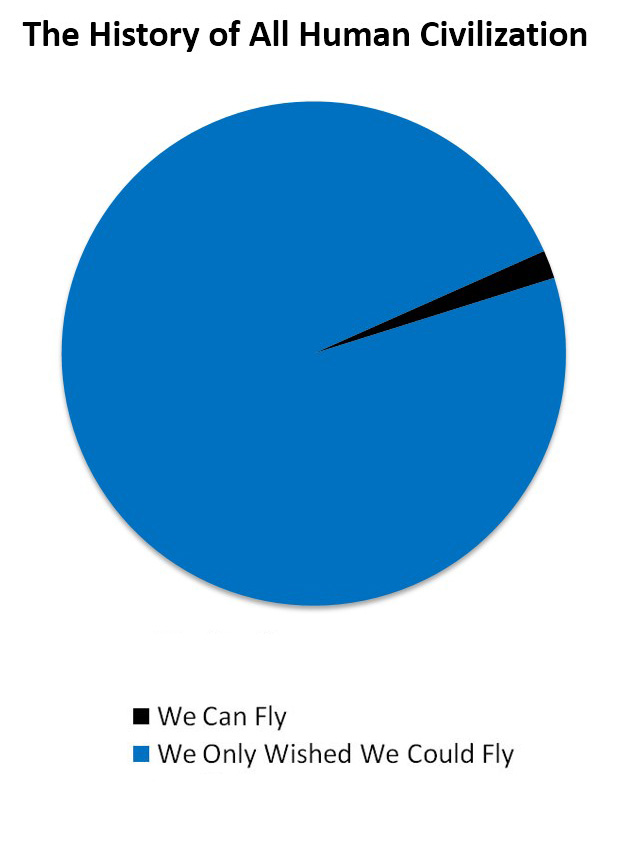

What matters is this: for the overwhelming majority of the history of human civilization, people wanted to fly but couldn’t. How lucky we are, then, to live in the utterly miniscule sliver of time when, if we want to fly, we actually can. Our reality would surely seem as ridiculous to King Bladud as his legend seems to us.