We Built a Thorp T-18 in Our Wisconsin Basement. But How Did We Get It Out?

Reposted with permission from AvGeekery.com

By Bill Walton

Aviation has been a large part of my family’s life for nearly a century. My grandfather, Kenneth B. Walton, imported a de Havilland DH.60G Gipsy Moth biplane after spending time in England. Known for his popular Kents restaurants in Atlantic City, my grandfather also worked on P-47 Thunderbolts for Republic Aviation at Farmingdale on Long Island during World War II before returning to his home on Brigantine Island in New Jersey.

His son John G. Walton II (my father) was first introduced to aviation in a Fleetwings F-5 Sea Bird amphibian. Dad later informally learned to fly in Navy T-28 Trojans and TV-2 Shooting Stars from instructor pilot friends during his service as an engineering staff officer with Navy Advanced Training Unit (ATU)-200 and ATU-202 deep in South Texas at Naval Air Station (NAS) Kingsville. He obtained his private pilot certificate in 1960 and his IFR rating in 1984.

Dad sometimes flew a Cessna 172 (78 Sugar) out of Atlantic City’s Bader Field while we lived in New Jersey. That’s where my first flight took place over Atlantic City and out over the ocean and our house on Brigantine. I was thrilled but also only 7 or 8 at the time. My very first trip on an airliner was a TWA DC-9 to the Air Force Museum in Dayton — to see a real B-17 of course.

Dad had wanted to build his own airplane for quite some time when his work took the family to Neenah in Wisconsin, just up the road from Oshkosh, in the early 1970s. He went to his first EAA Oshkosh that first year. Bitten by the bug in a serious way, he bought a set of plans for John Thorp’s T-18 design and the required sheet aluminum of various thicknesses then started forming parts and recruited meas chief rivet bucker and quality control inspector. Strange noises emanated from our basement at odd hours. Did I mention the T-18 was being built in our Wisconsin basement?

When you live in Wisconsin and you want to build an airplane, you might be fortunate enough to have several options. Perhaps the easiest one is to use a barn, detached garage, or other outbuilding that is either already heated or can be heated. After all, it gets really, bitterly, unimaginably cold in Wisconsin and progress toward the first flight of an airplane would certainly be reduced during the winter months without available heat. It’s difficult to effectively wield tin snips or back up a bucking bar with mittens on. An attached garage might also be an option, again provided it could be heated, and that the family truckster would survive daily liberal cold-soakings in the elements while work on the airplane in the garage progresses. Engine block heaters should be standard equipment on vehicles sold in Wisconsin.

One other option is available to many Wisconsinites. Many Wisconsin homes come equipped with basements. In this writer’s opinion, no house should ever be built without a basement. Providing endless options for usable space that by nature is always cooler than the rest of the house, but warmer than winter’s frozen embrace outside, basements are, in a word, perfect. But when one decides to use one’s basement to build an all-metal homebuilt airplane, at some point in the process (preferably early) one must consider how the airplane will inevitably and eventually emerge from the basement. This somewhat thorny problem often renders the basement a non-starter as an aircraft construction zone.

We talked occasionally about how we would get the airplane out of the basement. Because the house was built up a bit higher than the houses on either side of us and the basement floor was closer to ground level on the north side, the plan we spoke about most often was to blow a hole in the north side basement wall, dig out/redistribute enough of the berm dirt to create a ramp, and just roll the flying machine out. To the best of my recollection we didn’t talk about the method we ended up using very often if at all, but it made more sense than the basement wall hole idea. Seriously, calculating how much dynamite would create a suitably sized hole in the basement wall without collapsing the two-story house above it required some serious head-scratching.

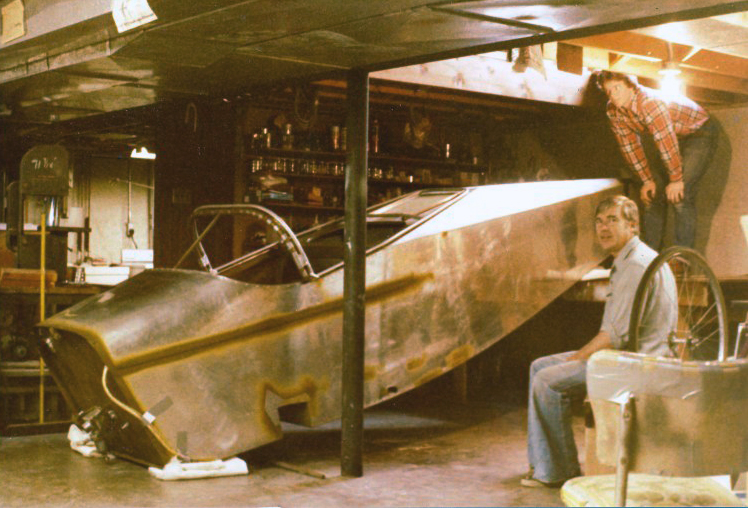

Then came word, not long before I graduated from high school, of an impending family move to Houston. The discussion about extraction of the airplane from our basement got real in a big hurry. The house went on the market. Dad went to Houston to find a hangar (and a house for us). But we had been working on the plane for six years in the basement. The fuselage was probably 90 percent structurally complete, as were the wing sections and tail sections. The engine was in the basement as well. So how did we remove the airplane from the house? Here’s how:

First, we dis-assembled the inner and outer wing panels, engine and landing gear frame, and tail surfaces from the fuselage yielding several pieces of manageable size and weight to move. Then we moved the dining room table into the living room. After that we rolled up the carpet in the dining room. Naturally we next removed the chandelier from the dining room ceiling. Of course we reinforced the ceiling joist from which the dining room chandelier had unsuspectingly been hanging.

We installed a block and tackle/pulley system in the reinforced ceiling joist in the dining room ceiling. Then it got real — we cut a large, but no larger than necessary, hole in the dining room floor and saved the floor section we removed, removed the upper and lower sash from the dining room window, and then we, and by we I mean I, used the pulley system to lift the wing sections, the fuselage, and the engine up into the dining room and then pushed them out the dining room window. The fuselage fit through the opening with about an eighth of an inch to spare on either side. That made Dad very happy indeed.

After that it was a snap. We built wooden crates to protect the main components during shipping (moving) to Houston, re-installed the section of dining room floor and carpet (the China didn’t rattle in the dining room hutch any more afterward), and repaired the ceiling and re-hung the chandelier. Did I mention we were showing the house while all of this was going on? Please watch your step in the dining room!

A little more than two years later, Dad and my youngest brother Lee departed David Wayne Hooks Memorial airport in Houston bound for Oshkosh for dad’s first trip to EAA Oshkosh as a T-18 builder and owner. Over the subsequent years dad flew his T-18 to Oshkosh every year he could and all over the rest of this great country. He installed folding wet wings in it. The T-18 we all built together in our Wisconsin basement won awards everywhere it went and sometimes still does. Dad lost a seven-year battle with cancer at home in Houston during the 1988 fly-in. Because he was such a staunch advocate of EAA from its beginnings in founder Paul Poberezny’s basement through its formative years during the 1970s and 1980s, so active in his local EAA chapter, and a friend to and willing conspirator with so many builders around the world, his name appears on the Memorial Wall at EAA headquarters in Oshkosh and he is still fondly remembered by T-18 enthusiasts and EAA members nearly 30 years after his untimely passing.

Mom finally sold the T-18 she and Dad had flown in so many times together to one of Dad’s good friends, who recognized how well it was put together, not long after Dad’s death. And my brother Lee? He has built or rebuilt several T-18s himself, always using the same distinctive paint scheme Dad created for his T-18. Lee runs the Thorp T-18 community website and is a true ambassador for the T-18 and experimental aircraft in general. He has also been for many years good friends with the family friend who bought Dad’s plane. He’s doing a great job keeping the family name in the T-18 business. MY grandfather’s great grandson and Dad’s grandson, my son John, has flown in the plane his grandparents, father, and uncle built several times now. He might even learn to fly in it himself. We’re just keeping aviation in the family. Four generations and counting.

Speaking of keeping it in the family, ride along with Lee and his wife Jamie in his latest T-18 on a quick flight south of Houston.