By Ian Brown, EAA 657159

Why would anyone put an autopilot (AP) in a homebuilt? Don’t you lose all the fun of flying? I might have thought that way when I first started to build my RV-9A, but as time went on I realized that sometimes a helping hand can be well, handy, so to speak, but let’s rewind a bit.

The $100 hamburger can be fun, and the collegiality of a bunch of pilots flying to a local rendezvous is pleasant, but more and more, my mission has been to fly longer trips to new, more distant destinations. Destinations like Florida or flights across the country involve many hours in the air, and it’s tiring and sometimes difficult to maintain heading and altitude by hand when you need to consult the map, look for a frequency, or make a radio call. Of course, life is much easier with a copilot, but they’re not always available. Sometimes you might want to have a nonpilot companion next to you.

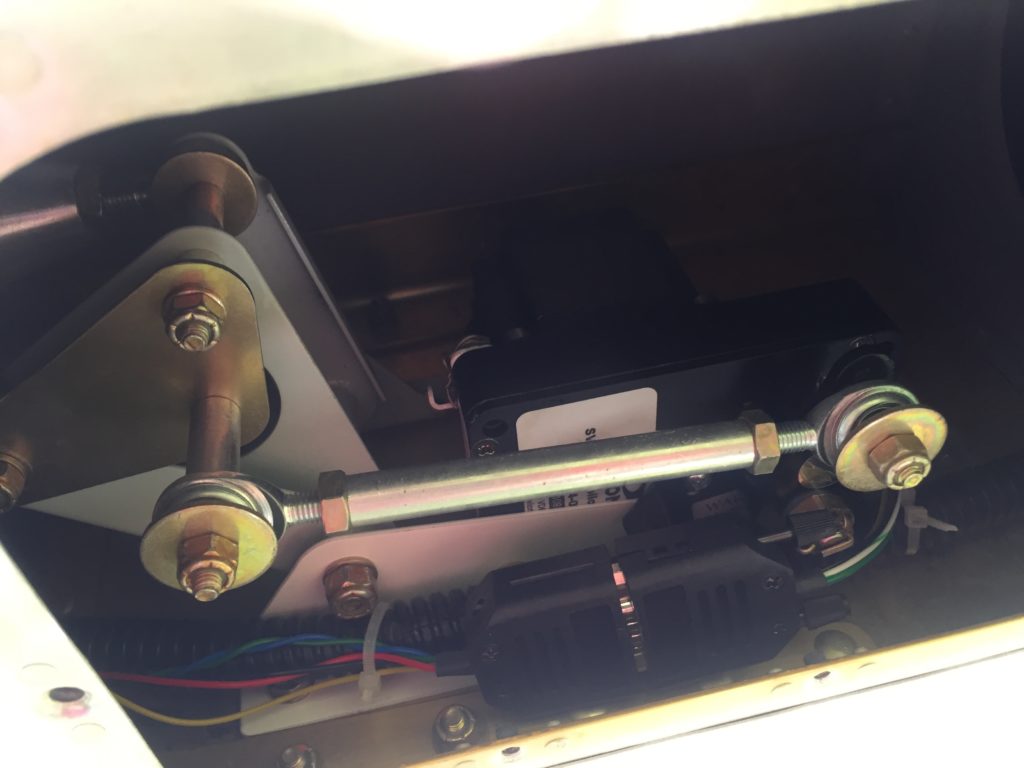

My Dynon D10A is a very compact but extremely functional box of tricks. Its software provides an amazing array of capabilities, but one I wasn’t expecting was that it already contained the capabilities of an autopilot. All I would need were the servos mounted in the right wing and behind the baggage compartment. Dynon Avionics does sell an AP74 autopilot controller, but in my case it wasn’t needed. All I really had to add were the two servos and associated disconnect button on the stick.

JP Riendeau, a close friend, EAA 498455, and until recently an RV-6A owner, helped me perform the in-flight portion of the 14-page calibration procedure. The first shocking discovery was at the moment of engaging the autopilot there was no shock. It just worked, very gently correcting heading and altitude errors almost imperceptibly. We put the autopilot through its paces, adjusting the heading bug, testing the ability to turn 180 degrees to a reverse course, changing the target altitude 500 feet higher, then lower, which not only tested the autopilot but its ability to work within the limits installed in the setup procedure. You can say “never bank more than so many degrees,” “never climb with an airspeed lower than this,” “never descend faster than at this airspeed,” and much more. You can override the autopilot by just pushing the stick, but it’s more comfortable for the pilot to just disengage it with the push of the AP button and then reengage it with a longer push of the same button.

I know that many of you might be extremely familiar with the use of an autopilot, so I’m talking to the rest of you. I have no idea what the addition of an AP might have done to the financial value of the RV, but I’m convinced that it’s a strong enough selling point that it will probably hold its value forever. It will also develop in me as a pilot another level of skill, but mostly, I think I’ve invested in a device that will make me a safer aviator.

What a blast we had today. The final thrill was when, 5 nm out, I dialed in the circuit altitude of our local airport and let the autopilot take us there. We arrived at that altitude about a mile early, right on the button after a graceful round-out, and I just let the AP take us into the downwind while I reduced power. The AP kept the altitude rock solid as the airspeed slowed to below the max flap extension speed. As the flaps dropped I disengaged the AP, turned base, and settled into the calmest base/final and shortest landing I’ve had in a while. I’m not saying I’m going to fly this way all the time, but wahoo, yay for autopilots!

This article first appeared in Bits and Pieces, EAA’s newsletter for builders and aviators in Canada. Subscribe here >>