Most people, even if they’re not serious film nerds like me, can name most of the actors who’ve played James Bond — Daniel Craig, Sean Connery, Roger Moore, and Pierce Brosnan at least. The better informed will chime in with Timothy Dalton and George Lazenby, while the real nerds (again, like me) will mention Barry Nelson who played the role just once during a TV special in 1954. (And don’t get me started on David Niven and Bob Simmons.)

But there’s another name to add to the list: Ken Wallis. Granted, Ken didn’t technically act in the role, but he did double for Connery during a spectacular flying sequence in 1967’s You Only Live Twice, flying a single-seat WA-116 autogyro of his own design named Little Nellie.

But being James Bond wasn’t the coolest thing he ever did. Pilot, inventor, record-breaker, racer — Englishman Ken Wallis was all of these things. With his classic RAF mustache and, later, tidy Van Dyke beard, he looked like he might challenge you to a duel — epees at dawn, that sort of thing — but, in reality, he was far more likely to ask you if you’d like to go flying.

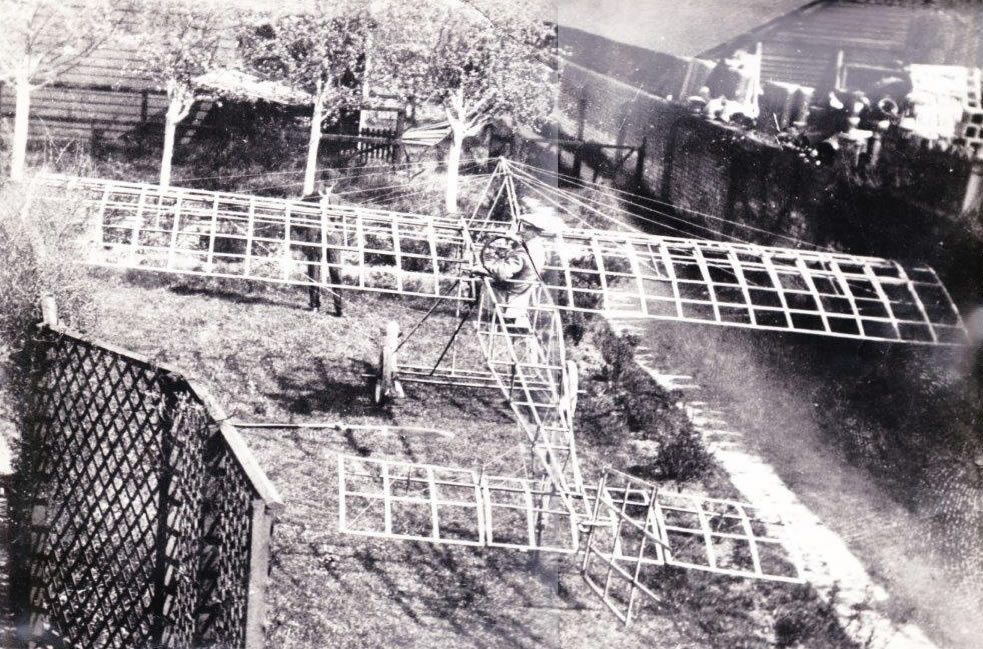

Engineering, and, to a lesser extent, aviation, were in Ken’s blood. In 1908, before he was born, his father and uncle, a couple of Edwardian gearheads who built and raced motorcycles, built an airplane. While the Wallbro Monoplane wasn’t a raging success, it flew several times, starting in 1910. It was advanced for the day, looking a bit like a Bleriot, but built from steel tubes and sporting actual hinged ailerons among other refinements.

Ken was born six years later in Cambridgeshire, England. As a kid, he loved machines, tinkering not only in the family motorcycle business, but also with radios and an early television, along with his father. They even played with an early fax machine, of sorts.

When he was 11, like a lot of kids, he wanted a motorcycle. Unlike most kids, he built one, followed by a boat and a race car based on his Austin 7. By the time he was 20, he’d taken over the family business. With land and sea covered, Ken decided it was time to fly and began flight training, earning his license after 12 hours of training in a de Havilland Gipsy Moth.

In 1938, with war looming, he applied for a commission in the Royal Air Force. All went well until the physical — Ken was nearly blind in one eye. The doctor told him that he’d never be able to land an airplane. Ken proudly produced his license, but the doctor was not impressed. This was an inauspicious start, but Ken was determined to get in. He found a copy of the RAF’s medical standards manual, studied up on the vision test and, with some creativity, passed without any trouble on his next attempt.

While he was waiting to start his RAF flight training, Ken bought a two-seat glider for 30 shillings — the math is tricky, but some estimates put that right at $100 in today’s money — so that he’d have something to fly in the meantime. He started training in the Miles Magister, and then transitioned to the Harvard. He was rated “above average” in flight school, having at one point made an emergency landing after his Harvard’s battery burst at 10,000 feet, spraying acid into the cockpit, and onto his face and hands.

After flight training, he was assigned to fly the Westland Lysander, a workhorse of an airplane that was used for observation, artillery spotting, reconnaissance, and special operations. In 1941, Ken transferred to bomber command and transitioned into Vickers Wellington medium bombers.

Ken flew three dozen night bombing missions in the Wellington, returning to base in the early hours of the morning with his airplane riddled with holes from German antiaircraft batteries. After one sortie, he recalled removing 115 pieces of shrapnel from the bomber’s twin Pegasus engines. Another flight ended with his airplane in a field after hitting a (friendly) barrage balloon cable, nearly shearing off a wing while nursing the battered bomber home. On another occasion, Ken and his crew bailed out of the airplane when they ran out of fuel in the clouds over Lincolnshire.

In the middle of all this, when Ken was able to take short leaves, he converted the family lawnmower and his father’s bicycle to electric power, making life a little easier on the home front. Shortly after the war, he salvaged a starter engine from a German Junkers Jumo turbojet — likely from a Messerschmitt 262 — and used it to power a Petrel sailplane. He stayed in the RAF, flying Gloster Meteors and de Havilland Vampires, then spending two years on exchange with the U.S. Air Force, flying the massive Convair B-36, ultimately retiring in 1964.

In the late 1950s, Ken turned his attention to a type of flying machine that had long intrigued him — the autogyro. He built a modified Bensen B.7 gyroglider, added an engine, and redesigned the rotor head to make it safer. It first flew in 1959, and he was hooked. He began developing a series of autogyros, using them for research and development, regularly demonstrating them for the RAF and the British Army Air Corps for use in reconnaissance and surveillance missions.

In other words, spy stuff.

His first ground-up design was the WA-116 Agile. Several were built and tested for Cold War special operations to extract high value assets — more spy stuff. He made repeated takeoffs and landings from the decks of small ships and the beds of even smaller trucks. Multiple variants followed, including a two-seater, and the WA-117, powered by a 100–hp, Rolls Royce-built O-200.

And then the silver screen came calling, but it wasn’t Bond, not yet. Ken’s first film job was in an Italian knock-off spy caper called Dick Smart 2.007. His WA-116 doubled as a flying Vespa scooter, which is arguably the most plausible — and comprehensible — part of the film. Ken was interviewed by BBC radio before traveling to Brazil to start filming, and a retired RAF group captain named Hamish Mahaddie heard the segment and called Ken immediately. Hamish had done consulting and flying for a number of aviation films in the ’60s (and would go on to work on the 1969 classic, The Battle of Britain), and, after a short demo, arranged for Ken to fly in the upcoming Bond film You Only Live Twice.

In the film, Bond is sent to Japan to investigate ongoing sabotage of the U.S. and Soviet space programs. When he needs to do some aerial recon, he calls for Little Nellie. Little Nellie was a WA-116 that Ken had bought back from the British Army and was using for his own testing and demonstration purposes. For the film, it was outfitted with a number of gadgets including air-to-air missiles, rockets, aerial mines, a forward-firing machine gun, and a rear-firing flame thrower. All of these come into play in the film as Bond is attacked by — and, naturally, defeats — four bad guys in Bell 47 helicopters while flying over, and in, the crater of the Shinmoedake volcano.

In all, Ken made 85 flights, logging more than 46 hours on location in Japan and Spain, all for just six minutes of screen time.

Ken played James Bond onscreen, but, throughout his life, he was also a real-life Q, constantly coming up with new gadgets. He invented a 100-shot spy camera that could be worn as a watch, and several miniature pistols, some as small as one inch, all fully functional. He also designed the world’s first electric slot car race track. He held multiple patents, and was as proud of those as he was the 32 autogyro world records he set beginning in 1968. Remarkably, eight of those records still stand today.

Ken worked with a number of other film and television productions over the years, and continued demonstrating his autogyros well into his 90s.

Ken died in September of 2013 at the age of 97. In terms of longevity alone, he lived more than most, but, given his life of adventure, Ken was a Renaissance man who certainly lived more than twice.