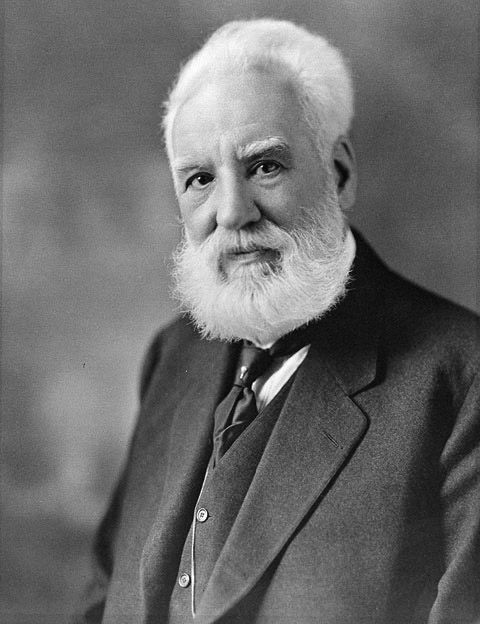

Back in the last century, a group of guys who were really interested in aviation got together and formed an association focused on experimental aircraft. The group was founded by a man with a knack for leadership, and a seemingly limitless curiosity, a man whose name remains well-known to this day. You know his name, but if this trite little trap is working, you’re thinking of Paul Poberezny, and not the man who invented the telephone. That man’s name is Alexander Graham Bell, and the group he put together was the Aerial Experiment Association, known by its anagrammatically familiar initials, AEA.

Bell, who was born in Scotland and immigrated to Canada in his early twenties, had been a tinkerer his entire life. In 1863, when he was 16, he and his older brother built a talking mechanical head that could say the word “mama,” thanks to a fake larynx and bellows that stood in for lungs. About a dozen years later, he was issued the first U.S. patent for the telephone, winning a photo finish race against a competitor and, in the process, changing the world forever.

Among his wide-ranging interests, Bell held a long-time fascination with aviation. In 1893, nearly 10 years before the Wright brothers’ success at Kitty Hawk, he made that fascination clear in an interview with McClure’s Magazine.

“I have not the shadow of a doubt that the problem of aerial navigation will be solved within ten years,” he said. “That means an entire revolution in the world’s methods of transportation and of making war.”

He began spending time with people like Samuel Pierpont Langley, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and Octave Chanute, both of whom were actively tinkering with flying machines, which spurred his interest. Working from his home in Nova Scotia, Bell experimented with a series of steam-powered model helicopters before focusing his attention on kites of all shapes and sizes.

In December of 1903, shortly after Bell’s friend Langley tested his full-size flying machine in the second of two failed attempts, the Wrights flew their Flyer, cementing their place in aviation history. Bell was intrigued but skeptical, given the general lack of publicity around the Wrights. In fact, it wasn’t until two years later, in December of 1905, when Bell was finally convinced they’d actually flown, thanks to an eyewitness account from Chanute. It was tidily ironic that, in 1910, Bell was asked to present the Wrights with the Smithsonian’s Samuel P. Langley Medal for Aerodromics. His skepticism was long gone by then as he declared that the brothers were “eminently deserving of the highest honor.”

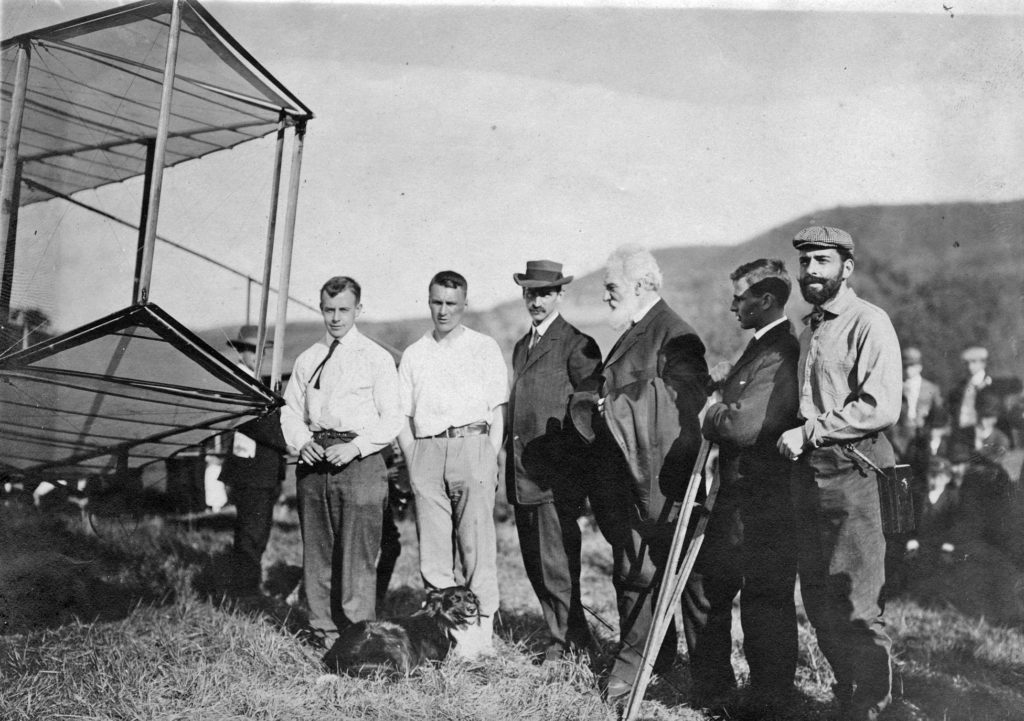

In 1907, at the urging of — and with considerable funding from — his wife Mabel, Bell formalized his aviation interests and founded AEA along with two of his associates, John A.D. McCurdy and Frederick “Casey” Baldwin. McCurdy and Baldwin were recent graduates who’d studied engineering at the University of Toronto. Also joining the group was the legendary Glenn Curtiss, a motorcycle designer turned aviation pioneer, and Lt. Thomas Selfridge, one of the U.S. Army’s first three dirigible pilots, who came after Bell wrote President Theodore Roosevelt a letter specifically requesting him.

Bell described AEA as a “cooperative scientific association, not for gain but for the love of the art and doing what we can do to help one another.” When founded on September 30, 1907, its official one-year mission was described as “carrying on experiments relating to aerial locomotion with the special object of constructing a successful aerodrome.” Over the next year and a half, they did just that.

AEA’s first flying machine was a massive and complex tetrahedral kite dubbed Cygnet I, which, when towed behind a steamer, lifted Selfridge up to more than 150 feet before the wind died down. A crew member failed to cut the tow rope when he was supposed to, so the kite was destroyed as it was drug through the water and Selfridge narrowly escaped his first aircraft crash. After building another kite, AEA moved on to a biplane glider, similar to what to the Wrights were flying in 1902-03. The group divided their time between Baddeck, Nova Scotia, and Hammondsport, New York, Curtiss’ home base.

The idea behind AEA was that each member would design an aircraft, and the team would work together to build them in succession. Selfridge was first up with his Red Wing, named for the leftover kite silk that they used to cover the wings. Red Wing was a pusher biplane, powered by a 40-hp Curtiss engine, featuring a small canard elevator in front and a fairly conventional-looking rudder and horizontal stabilizer at the tail. Baldwin flew Red Wing’s first flight on March 12, 1908, off frozen Lake Keuka in New York, covering a total distance of 318 feet, making history as the first public airplane flight demonstration in North America. Five days later, Baldwin flew the airplane again, but a gusty crosswind led to it dragging a wing on the ice and crashing. Baldwin wasn’t hurt, but the airplane was damaged beyond repair.

Next up was Baldwin’s design, covered in cotton muslin and known as White Wing. While Red Wing relied on the pilot shifting his weight for roll control, Baldwin’s airplane employed what Bell called “movable wing tips,” what we’d call ailerons. In addition, it had wheeled landing gear, not the simple skids of the previous airplane. Baldwin flew White Wing for the first time in May of 1908, followed by Selfridge and then Curtiss, who flew a distance of more than 1,000 feet, a group record at that point. McCurdy flew it next and last; just like its predecessor, White Wing fell victim to a gusty crosswind and was destroyed, though McCurdy walked away.

About this time, Scientific American magazine was offering a trophy and $25,000 in cash — nearly $700,000 today — to any pilot who could make a public flight of a least one kilometer. The magazine tried to entice the Wrights to compete, but they were still keeping their aircraft close to the vest. That said, anyone wandering around Huffman Prairie in Ohio as far back as October of 1905 could have watched Wilbur Wright fly a staggering 40 times that distance (in circles), if they’d known to look. While the Wrights were still using skids and a catapult assisted launch, and the Scientific American group specified an unaided launch from level ground, it’s almost certain that they could have won the cup had they been interested.

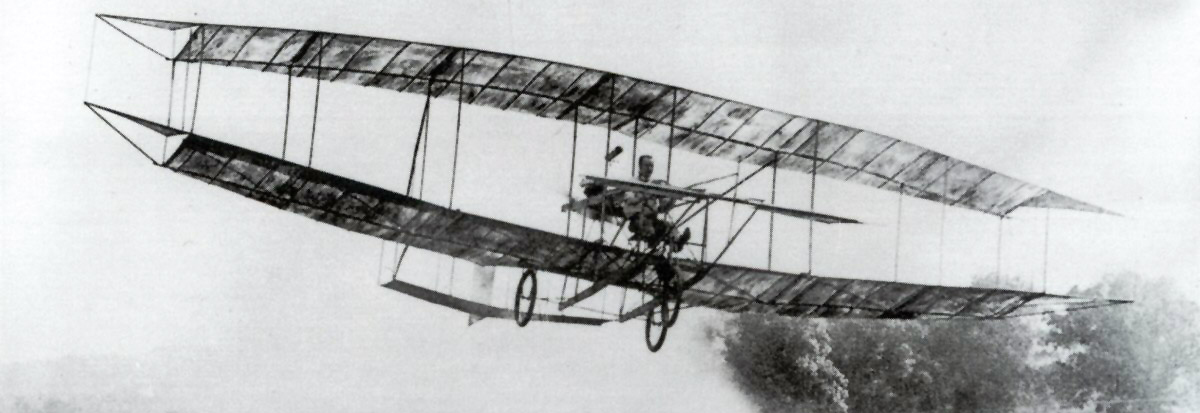

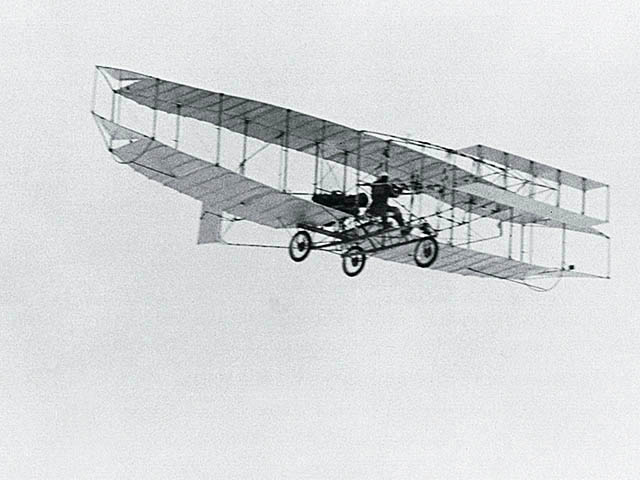

Luckily for AEA, and Glenn Curtiss in particular, they weren’t. It was Curtiss’ turn to design the next AEA airplane, and his June Bug (pictured at top of page), continuing to build on the lessons of the first two aircraft, made its first flight in June of 1908. A few weeks later, on July 4, Curtiss flew June Bug a distance of more than 5,000 feet, easily winning the first Scientific American Cup. June Bug continued to fly, making more than 100 successful flights before Curtiss put it on floats and renamed it Loon. It was unsuccessful as a floatplane, and sank in January of 1909 during a takeoff attempt.

Along with the trophy and the prize money, Curtiss and AEA also won the attention of the Wright brothers, who alleged that the June Bug infringed on their patent for a three-axis control system, eventually starting a series of legal battles that would continue for years. In September of 1908, the Wrights began making public flights of their own, with Wilbur wowing European crowds in France and Orville doing demos for the Army at Fort Myer, Virginia. Based on his experience with AEA, Selfridge was on the board to determine whether or not the Army would give the Wrights a contract. The Wrights weren’t wild about this, given their competitive relationship with AEA. In a letter to Wilbur, Orville wrote of his thoughts on Selfridge.

“I don’t trust him an inch,” he wrote. “He is intensely interested in the subject, and plans to meet me often at dinners, etc. where he can try to pump me.”

As fate would have it, Selfridge would never have a chance to spy on the Wrights for AEA, if he’d ever had that intention to begin with. On September 17, 1908, he and Orville took off on a demo flight and, a short while later, one of the Flyer’s propellers splintered, severing a control cable, and the airplane crashed into the parade ground and flipped onto its back. Orville was seriously injured but eventually recovered, but Selfridge died a few hours later, the first passenger to die in a powered airplane crash.

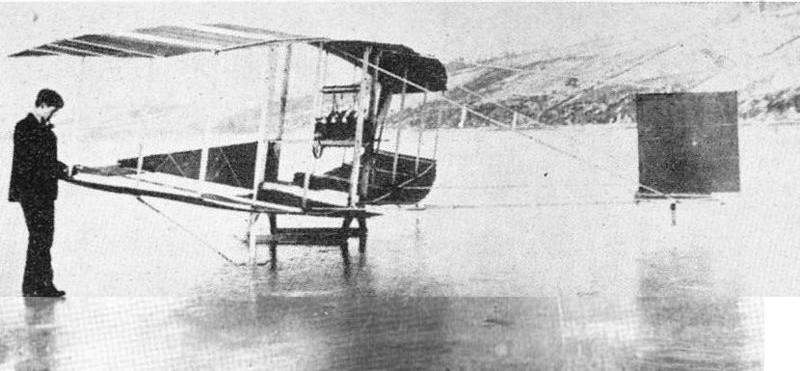

Selfridge’s death hit AEA hard, but they decided to keep at it, and extended their charter for an additional six months. Their next project was McMurdy’s design, which would come to be known, thanks to some silver balloon material they bought from Goodyear, as the Silver Dart. Evolving as it did from the previous AEA designs, it was a biplane with a rear rudder and twin canard elevators, tricycle landing gear, and this time powered by a water-cooled 35-hp Curtiss engine in a pusher configuration. Silver Dart was test flown a few times in Hammondsport and then shipped to Baddeck. On February 23, 1909, with McMurdy at the controls, it became the first powered heavier-than-air aircraft to fly in Canada. The Dart flew extensively after that, until it was destroyed in a landing accident during a military demonstration several months later.

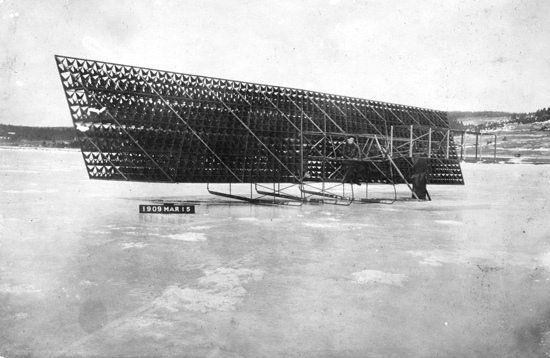

Most people consider the Silver Dart to be AEA’s final design, but that’s not quite true. The team had been working on another “aerodrome,” an updated and powered tetrahedral kite called Cygnet II. It was tested briefly, and unsuccessfully, before loaning its engine to the Dart. Once the Dart had proven successful, the group revisited the Cygnet II, and installed a larger 70-hp Gnome engine. It flew, but only barely, reaching altitudes of a foot or two and remaining in ground effect. To look at it, it’s hard to believe it accomplished even this much as it looks more like an over-engineered bridge than an airplane.

On March 31, 1909, the charter expired and AEA ceased to exist. The surviving members, less Curtiss who’d already moved on to start the company that would permanently establish his role in aviation history, gathered at Bell’s massive Beinn Bhreagh estate to watch the clock run out. Writing later, Bell said, “The AEA is now a thing of the past. It has made its mark upon the history of aviation and its work will live.” He was right. The aircraft of AEA popularized concepts like ailerons and tricycle landing gear and, more importantly, the concept of aviation itself, having made a number of public flights while the Wrights worked effectively in secret.

Baldwin stayed close with Bell, working with him on a number of innovative projects, mostly involving high-speed watercraft. He eventually served as director for what would become famous as Bell Labs, and died at age 66 in 1948. McCurdy went on to start the first aviation school in Canada, and was the first manager of Canada’s first airport. He was heavily involved in aircraft production during both World Wars, and eventually served as Nova Scotia’s lieutenant governor. McCurdy died in 1961 at the age of 74.

Over the years, Bell would continue to explore, to wrap his hands and mind around a wide array of interests, experimenting with everything from photography to desalinization, rudimentary fiber optics, metal detectors, air conditioning, sheep husbandry, and composting toilets. Toward the end of his life, he was involved in the eugenics movement, driven by his fears that deaf people — like his own mother — would exclusively intermarry and create “a defective race of human beings.” While horrific in hindsight, these weren’t necessarily uncommon views at the time. Within a couple of decades after Bell’s death, ideas like these had mercifully morphed from de rigueur to deeply disturbing, at least in most of the world.

Bell died on August 2, 1922, when Paul Poberezny was just 11 months old. About 30 years later another association of experimental aircraft pilots, craftsmen, and enthusiasts was founded, this one with no expiration date.