By Vic Syracuse, EAA Lifetime 180848

This piece originally ran in Vic’s Checkpoints column in the August 2020 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

This month I thought I would address a subject that has been on my mind for a very long time. It has to do with some of the trepidation I hear voiced pertaining to the initial airworthiness inspection of an amateur-built aircraft. In the 12-plus years that I have been performing designated airworthiness representative (DAR) services, I have only issued five denials across the hundreds I have certificated, and every one of the owners agreed. In one case it was on a Glasair II that was based at a 3,000-foot strip, and the firewall forward had basically been removed from another airplane more than 20 years ago and had not run since. That didn’t seem safe to me or the owner. In another case, as I was performing the inspection, it was clear to me that there was so much dirt, grime, and grease on the airplane that it appeared to have been flying quite a bit. When I asked the question, I was told it had been flying for more than three years. The owner had just “borrowed” an N-number from one of the derelicts on the field but now thought it was time to get it certificated. Wow! Another one was at a “pro shop” and was an RV-8 that had been wrecked, was put back together with rebuilt parts, and was then being represented as new. There looked to be 1,000 hours of oil and dirt in the aft fuselage.

The most recent one is what has prompted me to address this “theme” I hear in the community once in a while about builders not wanting a “real” inspection, but more or less a paperwork signoff. Dare I say some of it comes from an anti-authority mindset? I really don’t understand why anyone wouldn’t want an extremely thorough inspection of their project before it takes to the air. My approach to the inspection is that it should be the absolute best preflight the airplane will ever receive. Unfortunately, I do know of builders who shop around for DARs and flight standards district offices (FSDOs) that are more interested in the paperwork and only take a cursory look at the aircraft. This particular one was an opportunity to address it with a positive outcome.

Some of you may be aware that there is a new way to process the paperwork for the initial inspection called the Airworthiness Center on the FAA website. It’s supposed to be easier, but it is new and still has some challenges. In this case, the builder had called an FSDO in the southeast with a reputation for primarily paperwork inspections and was told that, due to the COVID-19 situation, representatives would not be traveling for inspections and recommended a DAR. In the process of working through the Airworthiness Center online, there were some challenges with selecting a DAR. Eventually, the FAA inspector, who was extremely helpful, ended up working with me to get it assigned to me in the system.

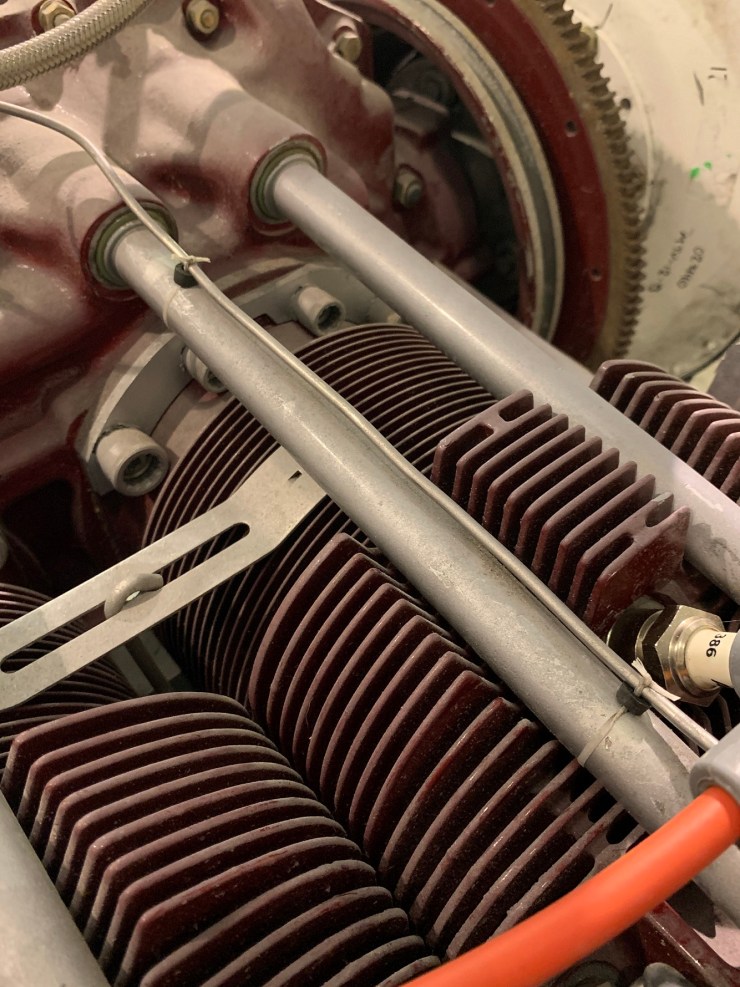

I went to perform the inspection. I will leave names and the type of aircraft out of this so I don’t make anyone uncomfortable because this eventually worked out for the best. I will tell you it was a very high-horsepower aerobatic airplane. It was one of the worst airplanes I have ever seen. I really think the builder was quite lucky it worked out that someone really physically looked at the airplane and understood what to look for. There were very serious problems, some of which could have been potentially life-threatening.

I’m sure you’re already thinking you know what I found, and you are probably right. I stopped counting when I got to 12 loose jam nuts. Most of my other pet peeves were there as well, such as unlabeled switches and fuses and unsupported electrical wiring. Then there were some real shockers. The injector lines were attached to the pushrod tubes with waxed cord lacing! There is a very specific AD that specifies the injector lines must be clamped every 6 inches. Yes, I know we can argue about ADs on amateur-built aircraft, but, to me, this one is not negotiable.

One of the injector tubes was severely kinked and needed replacing. The throttle cable was attached with a U-bolt that had only one nut on it. The gascolator was not safety wired, and there was no overflow tube on the fuel pump. Another shocker to me was that all of the bolts throughout the control system were hardware store coarse thread bolts, not even Grade 8! Remember, this is a high-performance aerobatic airplane.

I can usually tell if the engine has been run due to discoloration of the exhaust. This aircraft showed none of the discoloration, though the builder claimed it had been run for a couple of hours, even though a spark plug wire was disconnected. There was absolutely no builder documentation presented. None. Nada. My observation was that it had been assembled from not-necessarily-new pieces.

The sad thing is that there would have been multiple opportunities to not get to this point over the claimed seven years of construction. With all of the help available, such as technical counselors and the internet, there really shouldn’t be examples like this anymore. He also claimed it was his second amateur-built aircraft. There is help available, lots of help actually. I certainly hate issuing a denial as much as the builder hates receiving one, so I figured out we needed to get some of that help to this builder. This was an expensive lesson, and it was quite a ways from my home.

I spoke with a good friend in the area who has built multiple aircraft and was an EAA technical counselor and asked if he would be willing to help the builder. It turns out he had seen the aircraft and had already told the builder it was not ready. He agreed to help. Hopefully, that is already underway as I write this column.

I also took the opportunity to circle back with the FAA inspector from the local FSDO, as well as my managing specialist from the Atlanta Manufacturing Inspection District Office. Both were quite shocked by the report and pictures. It was a really super discussion with the FSDO inspector. Even he mentioned that he thought some of his fellow colleagues returned back to the office “rather quickly” when going out to perform amateur-built inspections. It’s not to fault the inspectors, as they really haven’t received training in the various amateur-built aircraft and they don’t know what to look for any more than I would know what to inspect on an airliner. Interestingly enough, he knew of me, has read my articles in various magazines, and was going to take the pictures to educate some of his colleagues. I’ve even offered to come and train them if they so desire.

To me, this was a great outcome. The builder is going to get help, and we get the chance to educate some FSDO inspectors. Both my managing specialist and the FSDO inspector will be joining me for the next inspection of the aircraft, but only when the technical counselor tells me it is ready.

So, for the rest of you, please don’t hesitate to use all of the resources available to you during the construction of your project. Very few denials are ever actually issued. And why wouldn’t you want the very best preflight for your new airplane? It will only help to make that first flight more fun.

Vic Syracuse, EAA Lifetime 180848 and chair of EAA’s Homebuilt Aircraft Council, is a commercial pilot, A&P/IA, DAR, and EAA flight advisor and technical counselor. He has built 11 aircraft and has logged more 9,500 hours in 72 different types. Vic also founded Base Leg Aviation and volunteers as a Young Eagles pilot and an Angel Flight pilot. For more from Vic, see his Checkpoints column each month in EAA Sport Aviation.