By Vic Syracuse, EAA Lifetime 180848

This piece originally ran in Vic’s Checkpoints column in the March 2021 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

As a flight instructor, it always seemed like a challenge to help new students understand the pitot-static system. I often wondered if it was the way I was explaining it or if it was just difficult to understand. Some of the most-often missed questions on the written and oral exams were related to the pitot-static system. As instructors, we even tried to create failures by covering up the static vents so the student would catch them on the preflight, and then we would have a discussion about expected failures. Sometimes they didn’t catch them, and it was very interesting to watch the reaction as we were lifting off. Yes, this was only done on good weather days.

All of that scenario discussion paid off for me one day when we were returning to Atlanta from Cleveland after having visited family for a week over Thanksgiving. It rained pretty good for about three days while the Bonanza had been tied down outside. We were departing into an 800-foot overcast. My usual procedure for an instrument departure is to establish a climb attitude, retract the landing gear as the end of the runway disappears under the nose, set climb power, check the engine instruments, and then transition to flight instruments prior to poking into the clouds. On this particular departure, everything looked and sounded normal, except I noticed that even though the climb angle looked correct, the airspeed was decreasing and the altimeter was not moving very much. I cross-checked the landing gear lights to make sure the gears were in fact retracted, even though I had heard them thump into the gear wells, and then checked the engine instruments again, of which all were in the green. Pitot heat was on, and I had checked that the pitot tube did in fact warm up on the preflight. It was then that the light bulb went off in my head. I activated the alternate static source and was immediately rewarded with a big jump in the altimeter and airspeed, about three seconds before we poked into the clouds. I was just starting to push forward on the yoke, as I didn’t want to enter the clouds with something not feeling right. The rest of the flight was normal. We blew quite a bit of water out of the static system when we got home.

There have been some pretty infamous landmark accidents due to pitot-static system errors that did not result in happy endings. One was Northwest Airlines Flight 6231 out of New York, which crashed due to pitot icing, and another was a 747 out of South America. The 747, Aeroperú Flight 603, had just come out of maintenance and the static ports had been left covered.

My reason for this topic is that we are seeing way too many static system problems on airplanes that come through our shop, and on prebuys as well, to the tune of at least two dozen over the last two years. Many of them are builder errors. Some of them are age issues. After listening to some of the comments I hear from various pilots, it is clear to me that many pilots still don’t understand the pitot-static system very well.

Here are a few cases in point. One owner asked us to replace the autopilot pitch servo in his RV-10. I first asked him to describe the problems. Without going into a whole lot of detail, it sure sounded a lot like the Bonanza scenario I described earlier. So, we first removed the baggage bulkhead where we could see the static connections. This airplane was tied down outside all year due to lack of hangar space, so I had my suspicions already. Sure enough, we must have removed about a cup of water from the static system. We rerouted the lines, and it has been fine since. More on routing problems later.

In another instance, we were performing a prebuy in our hangar when I overheard the seller telling the prospective buyer how fast the RV-8 was and that he had flown there at 2,500 feet indicating 192 knots. Now, I’ve been around RVs enough to know that they all fly pretty much the same. There’s only so much you can do with horsepower and airframe cleanup, and 192 knots at 2,500 feet just isn’t going to happen. I couldn’t help but butt in and mention that I was pretty sure he had a static leak. Sure enough, one of the static lines in the tail cone was completely disconnected from the static port.

Last summer we had a formation lead pilot come to our shop telling us that the rest of the formation was complaining he was flying too fast. Normal procedure is for the lead to fly at 120 knots, yet the rest of the formation claimed they were indicating 130-132. This causes problems for the rest of the formation, especially for number four, who may not have enough excess power to move around. This one was a surprise in that the static system had no leaks when we tested it and the static ports were installed correctly. Upon further examination, we noticed they were mounted differently, which could cause the problem. More on that later.

Recently, another pilot asked why the autopilot would cause a pitch-up movement when he activated the cabin heat. So, let’s discuss how the system is supposed to work and the causes of erroneous indications.

The two parts of the pitot-static system serve two different purposes. The pitot side is connected to the pitot tube at one end and to the airspeed indicator at the other end. The airspeed indicator (or the pitot port on the air data, attitude, and heading reference system) is the only instrument that is connected to the pitot tube. If you’ve ever stuck your hand out of a moving car or an open-cockpit airplane, you’ve felt the pressure and know that it increases as you go faster. The gauge is calibrated similar to any other pressure gauge, converting a pressure to an indication to help us make decisions. If the pitot tube were to get blocked with ice, a bug, or some other obstruction, the pressure will decrease and the airspeed will read lower than actual or, in some cases, go completely to zero. It is a good practice to turn on the pitot heat during flight in precipitation whenever the temperature is close to freezing for this reason.

The static system is there to sense the atmospheric pressure, which changes with altitude, so we are going to connect the static side to the altimeter. Another instrument — the vertical speed indicator (VSI) — tells us which way we are going by sensing the increase or decrease in atmospheric pressure, so we are going to connect the static system there as well.

Now, those of you who remember that the air gets less dense as we climb, and that I told you we provide pitot pressure to measure airspeed, are probably wondering if there is some kind of correction factor applied to the airspeed indicator. Yep — the static system gets connected to the airspeed indicator as well. It is the only instrument that receives both pitot and static pressure.

Given the static system is providing some really important information, we clearly don’t want it in an area where it will be affected by any higher or lower pressures on the airframe. Think about breaking out of the clouds at 110 knots and 200 feet! For most GA aircraft, this is the time when we really need it to be accurate; hence, the 24-month pitot-static check requirement for IFR flight. Most manufacturers will tell you where to place the static ports for optimum performance. Sometimes the manufacturer will tell you how the indications could be affected during different flight attitudes. Does anyone remember flying some of the Cessna 172s that had only one static port located on the forward left engine cowling? You had to pay attention when slipping the aircraft, as a right or left slip would give different airspeed indications. If I remember correctly, a left slip would cause a lower airspeed reading due to the static port receiving a higher-pressure static input. Most airplanes today have static ports on each side of the fuselage, or even located out on the pitot tube, so that aircraft attitudes do not affect the airspeed readings.

Now, let’s go back to the scenario where the lead formation pilot was reading a lower indicated airspeed. We noticed the static ports were quite elevated above the fuselage skin, as they were mounted on the outside rather than on the inside of the skin. We surmised it was having an adverse effect upon the static pressure. Changing them now would really mess up a gorgeous paint job. So, we added some ramps to smooth the airflow and nailed the indicated airspeed to within a knot. So, not only is location important but so is the physical distance above the skin.

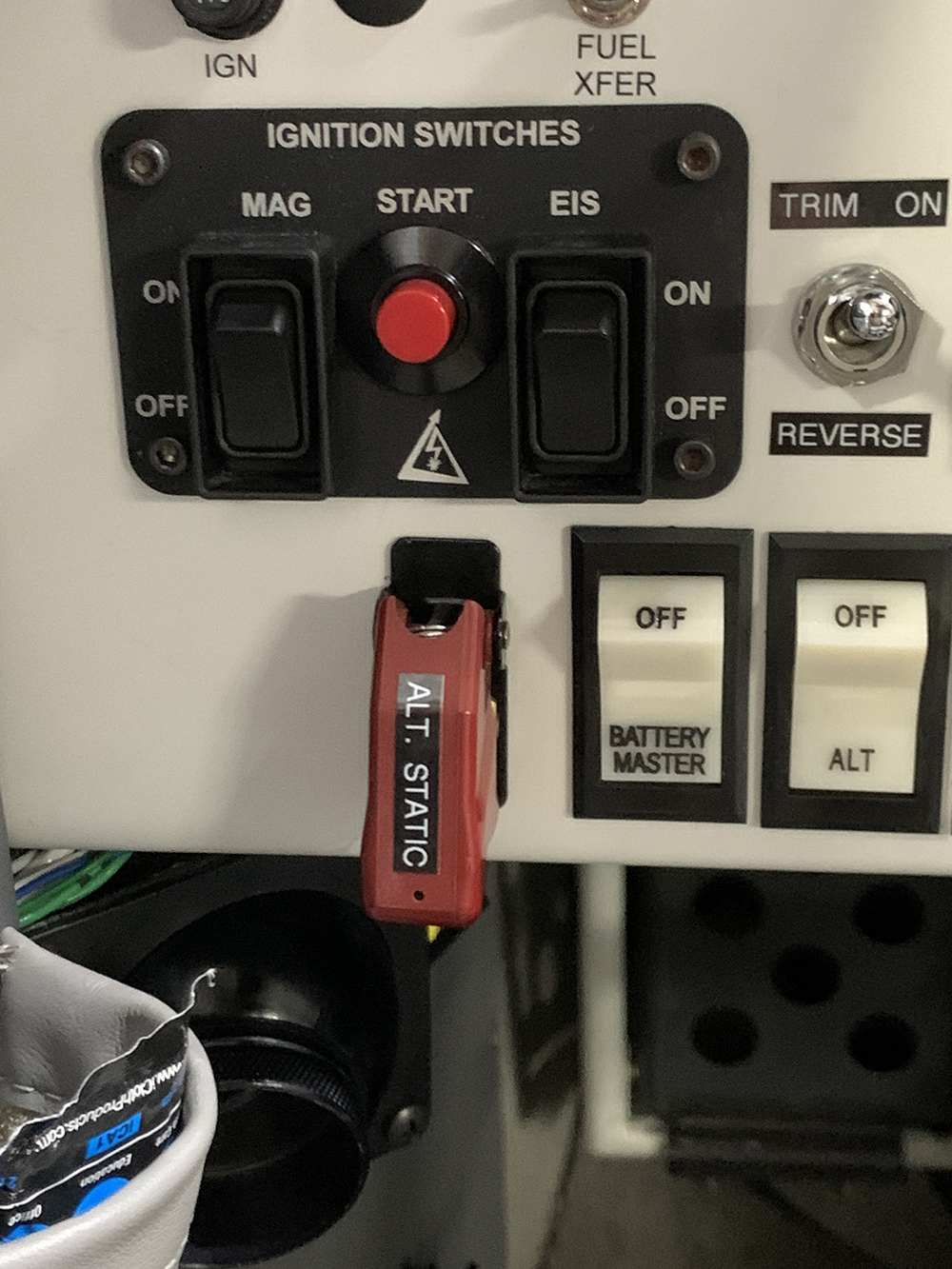

The biggest problems we are witnessing have to do with routing of the static lines to preclude water entrapment, and making certain the lines are supported properly to stay attached. All static lines should first route uphill at the port connection to eliminate the potential for water to collect in them. A blocked static line will cause lower readings on the instruments. A disconnected line inside the cabin of a nonpressurized aircraft will cause higher readings on the altimeter and airspeed. The VSI will only show a momentary direction change when the line is first disconnected. For those of you who have an alternate static source switch on your panel, you can test this regularly, with the autopilot disconnected of course. In level flight, activating the alternate static source will show an increase in altitude and airspeed and a momentary positive rate of climb. If you don’t see a change, then you have a leak. I routinely fly instrument approaches to minimums, so I have a switch and check mine regularly.

Now let’s circle back to the cabin heat causing a pitch-up. The problem is a static leak or broken static line connection within the aircraft cabin. Opening up the heat allows a ram source of air into the cabin, effectively adding some pressurization. The altimeter immediately decreases, and the autopilot tries to correct by pitching up.

By the way, for those of you with low and slow open-cockpit airplanes, there’s a good chance your static system is just vented to the cabin and is always reading high, for both airspeed and altitude. Want to do a quick check? Set your altimeter to zero prior to takeoff, and then fly down the runway at 10-20 feet visual altitude at cruise speed. Take a quick glance at your altimeter and I’ll bet it reads much higher. For those of you with higher-performance airplanes who don’t have an alternate static source, you can do this same test to verify the integrity of the static system.

So, now I’m hoping I’ve helped some of you better understand the pitot-static system and how to go about checking yours without needing an avionics shop. Be careful when flying over the runway at a low altitude. Take a friend along if you can and have them read the altimeter. It should be fun.

Vic Syracuse, EAA Lifetime 180848 and chair of EAA’s Homebuilt Aircraft Council, is a commercial pilot, A&P/IA, DAR, and EAA flight advisor and technical counselor. He has built 11 aircraft and has logged more 9,500 hours in 72 different types. Vic also founded Base Leg Aviation and volunteers as a Young Eagles pilot and an Angel Flight pilot.