Being on staff at EAA generally means that you do not have many boring days. There is always something to do, and it is always interesting. There are times that even the wildest imagination cannot prepare you for what is going to happen. A few weeks ago, Ben Page, EAA Aviation Museum collections curator, walked in with two EAA members joining him. They were Bill and Karen Murphy, EAA 1142521 and EAA 1092741. As they introduced themselves they told us that they had some B-17 artifacts which were in their hangar and that they felt might have a good home with us. As they started to describe the absolute treasures which they had, Bill simply started with, “Well you have heard of the Memphis Belle, right?”

As someone who has been in love with B-17s since I was a kid, there are certain examples that just have a special meaning. Almost 13,000 of them were built, but one remains arguably the most famous of them all. When first built, Boeing B-17F 41-24485 was just another B-17. 485 would be picked up by her pilots, Robert Morgan and Jim Verinis. It was while the pilots, Robert Morgan and Jim Verinis, were were in training in Washington that their B-17 was given the name which became famous. Morgan met Miss Margaret Polk of Memphis. She was in town helping her sister get settled after moving out there. Even though she really liked Morgan, she had a date set with another guy. Her sister would not allow her to break the date as it would be “unladylike.” Morgan knew when and where the date was going to take place, and repeatedly buzzed them with the B-17. The other guy didn’t stand a chance. Soon, Morgan and Polk began dating and his B-17 still remained without a name. Morgan’s nickname for Margaret was “Little One” and he was thinking of naming the plane that. Then one evening the crew went to a movie theater. They saw Lady for a Night. The film takes place on a riverboat which is named “Memphis Belle.” The lead actress played by Joan Blondell is referred to several times as “Memphis Belle” as well. After that, the crew felt that they had a good name for the airplane and artwork soon followed.

The airplane flew 25 missions over Europe from the end of 1942 through the spring of 1943. These early years of the air war had no easy missions. Several times the Belle was damaged on missions, however it always brought the crew home. The crew flew their 25th and final mission in May of 1943 and in early June was sent home on a war bond tour. They had become the first bomber crew in the 8th Air Force to fly their tour of duty and return back to the United States. Thanks to the William Wyler documentary filmed on B-17s in the 8th Air Force (several missions were filmed onboard the Belle), the crew returned home to a heroes’ welcome and the airplane now is proudly restored and on display in the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

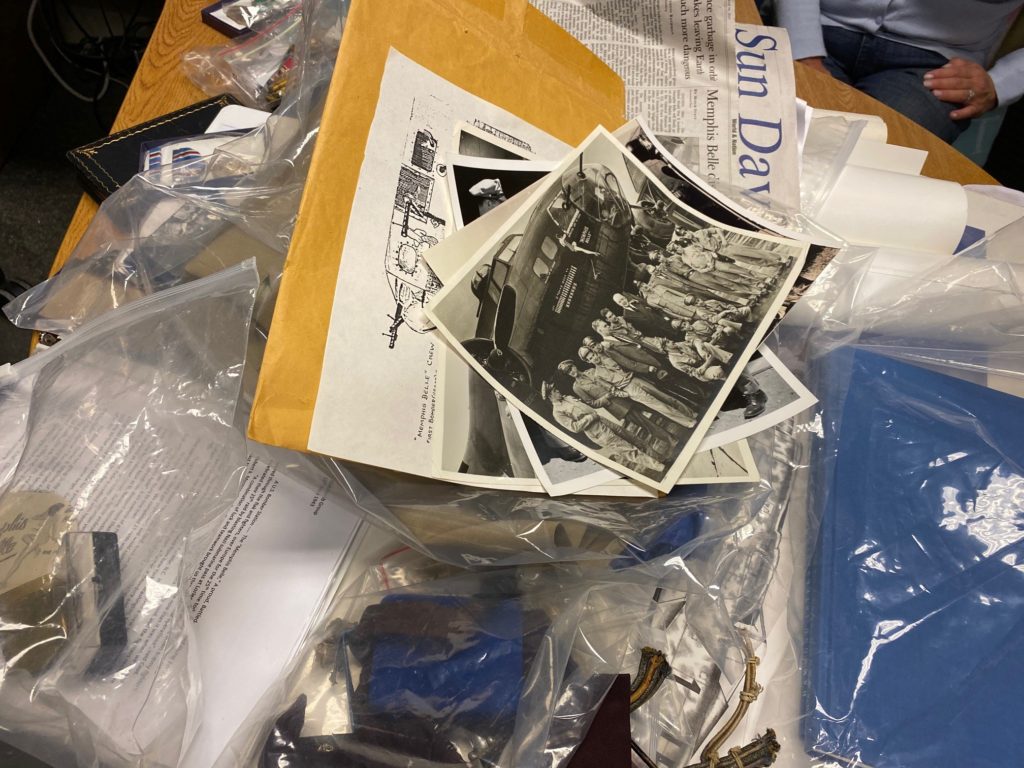

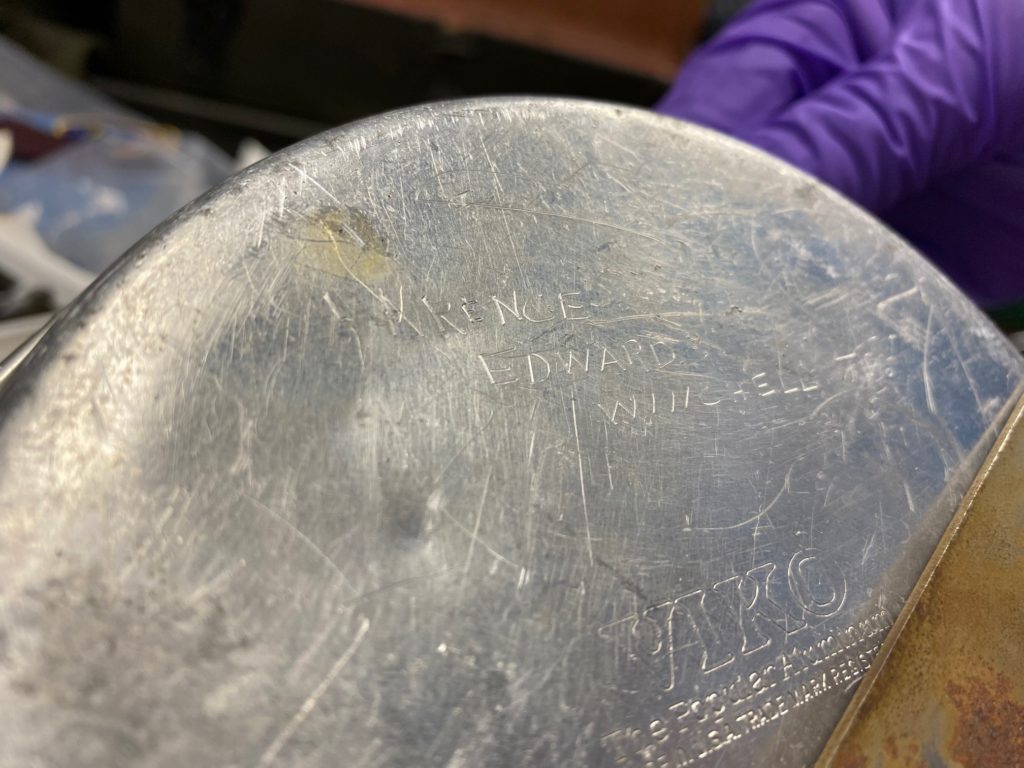

The personal items which Bill and Karen were going to share with our museum were items from the left waist gunner named Clarence “Bill” Winchell. The items included his WWII footlocker which contained items such as his uniform, medals, and a transcribed copy of his diary that he kept while flying his missions. I felt like someone who was working at the Baseball Hall of Fame who had just been given items from Babe Ruth’s closet.

Bill Winchell was born in Massachusetts, but soon moved to Oak Park, Illinois, which is where he considered home. The Air Corps was not his first choice to serve. He had always loved horses and tried to join a cavalry unit. That unit had a full roster so he was sent to a field artillery unit in Tennessee. He and a first sergeant did not get along well and when Bill saw a chance to leave and perhaps be of use in a different unit, he jumped at the chance. He transferred to the United States Army Air Forces. Bill had wrongly assumed he would spend the war in a position on the ground in the USAAF. At MacDill Army Air Field, later MacDill AFB, he discovered that he would have the chance to fly as they were looking for gunners to crew bombers. He would have to pass a physical to get the job, and worried about his somewhat poor eyesight. He had copies of the eyechart and memorized them so that he could pass. After completing training, he was off to Walla Walla, Washington, as a trained bombardier and gunner. When he arrived, he was told that he was assigned to the Morgan crew. Bill Winchell was now a waist gunner on the Memphis Belle.

Using his diary as source material, it has uncovered a remarkable look into the life of a crew member flying missions at this part of the war. It uncovered heroism never before mentioned in stories. The diary is written in real time for Winchell, as it was happening back in 1943. You can feel his emotions as he experiences events such as watching a friend fight to keep their burning B-17 in the air. His diary captures the moment. “Lt. Cliburn’s engine is on fire now. He is losing altitude and falling behind the formation.” He continues, “He got the fire out, but it is still smoking badly. Two ME’s spotted him and dove in for the kill. Our group’s guns caught one of them in our crosshairs and sent him spinning into the sea — serves him right.” Lt. Cliburn was able to limp his B-17 home.

Another entry is about the heroic act of a bomber crew with one engine out, who turned back despite their own damaged aircraft to cover another B-17 which was damaged worse. Together these two aircraft struggled to fly toward home. Seeing them struggle, the entire squadron made a turn which allowed the two aircraft to rejoin the formation. Then they all reduced speed. The squadron flew home together.

For Winchell, the war was personal. He mentions the airplanes’ names and always follows it with his friends who are onboard. His friend and roommate Jimmy Becktel from Grant, Nebraska, was a waist gunner on a B-17 that ditched in the North Sea on his third mission. Air-sea rescue was able to rescue him. On his next mission out, a German fighter shot his airplane down. “Quinlan [the Belle’s tail gunner] watched the fighter that got Beck’s B-17 and he poured a long burst into him until he dropped. That was for Beck.”

Having the chance to look over this diary and through some of the artifacts that came in is an amazing experience which I never imagined I would have. To see items which were there in the Memphis Belle for those 25 missions is really phenomenal for anyone interested in researching the subject. Knowing that we are going to be able to share these artifacts with those who come to the museum and preserve them for generations is a wonderful feeling which really charges you.

We are very thankful to Bill and Karen Murphy who have been such wonderful stewards of these items. It is because of them that they are still here with us today.