By Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the May 2021 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

Ben stood by the hangar door and looked up as the multicolored ultralight flew slowly over the row of hangars. The distinctive two-stroke whine reached his ears as he watched the aircraft rock its wings.

It’s a beauty, he thought.

Rick landed and taxied over to the hangar where Ben was standing. He let the engine idle for a moment and then cut it off. He took a long deep breath. “Incredible. Everything I thought it would be. Got advice from the seller, everything looks good, fair price, and exactly what flight should be: open-cockpit-bugs-in-your-teeth and wind-in-your-hair flight.”

“How old is this one?” Ben said. “Is it an ultralight?”

“It’s 15 years old. Yes.”

“Make sure you do thorough inspections. Some of those parts might need replacing.”

“Right,” Rick said.

Winter came to the rural Midwestern airport, and all was quiet until the April thaw revealed tiny strands of green emerging from the cold ground. As Ben was cleaning up the hangar in preparation for the flying season, he heard the familiar two-stroke and smiled. He walked outside to see Rick taking off to the east. As the aircraft reached 200 feet of altitude, the engine went silent.

I forgot how fast they quit, he thought. Land straight ahead.

Rick seemed to read Ben’s thoughts as he coolly lowered the nose in a dive to the runway. Straightening out and pulling back inches over the surface, he made a textbook emergency landing. Ben watched as Rick fiddled with starting it again.

No, Rick, don’t! Let’s find out what’s wrong, Ben thought as he jumped in his truck and drove over to the runway apron.

“That was a perfect landing you made, Rick.”

“Thanks. What a surprise. I wonder what went wrong.”

As they towed the aircraft back to the hangar, the aroma of gasoline floated up from the cockpit.

“That may be your answer,” Ben said.

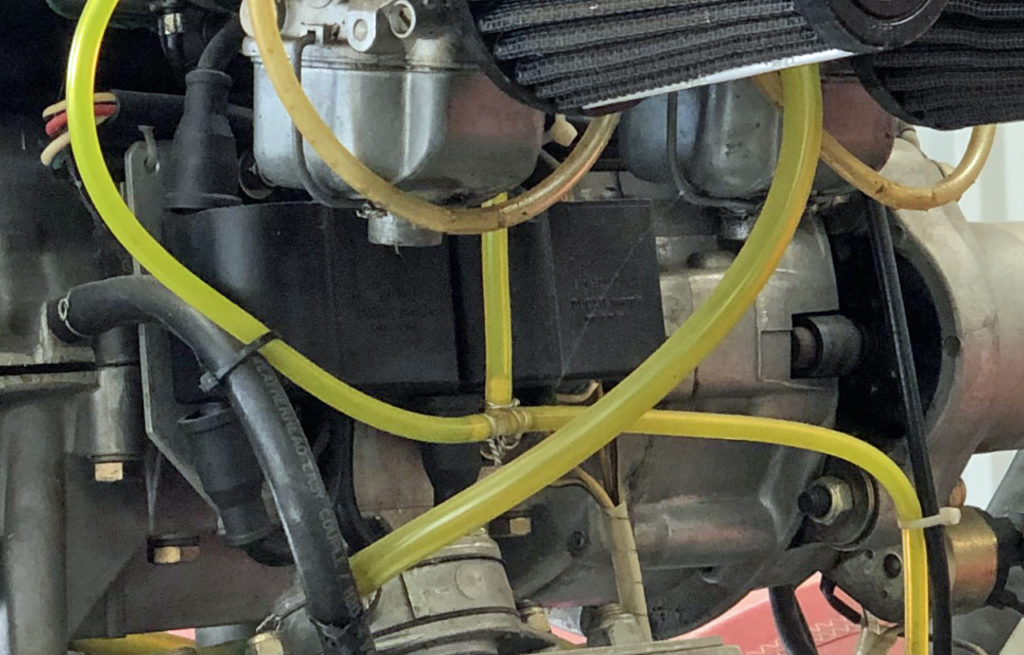

After an inspection, they discovered a brittle plastic fuel line under the pilot’s seat that had split.

“Hey, look at this, Rick,” Ben said as he pointed to a fuel filter that was also under the seat.

The inside was clogged with copper-colored gunk.

“How long has this gas been in here?” Ben said.

“Ah, through the winter?” Rick said sheepishly. “And, to be honest, I didn’t even know that filter and line were there, hidden under the seat.”

Ben looked at Rick and shook his head. That was all he needed to do as Rick looked down at the dusty hangar floor.

* *

“I intend to live forever,” comedian Steven Wright said. “So far, so good.”

Everything is on a journey through time. “Time-limited” and “condition-limited” — what’s the difference? Does it matter if we’re following a reliability-centered maintenance philosophy? Everything in life is “condition-limited,” including us. You’ve probably noticed this already. There’s a clever little gremlin hiding in our airplanes, too. The gremlin’s name is Time. Aside from stating the obvious, what should we be paying attention to?

Visiting projects over the years has turned up data that I will share. Here are the top problems caused by items that are particularly prone to wearing out early — or are just plain surprises that we might not see coming.

First, some definitions:

Life-limited parts. According to the FAA, life-limited part means “any part for which a mandatory replacement limit is specified in the type design, the Instructions for Continued Airworthiness, or the maintenance manual.”

Time-limited parts. Based on time or cycles, items such as helicopter rotor blades or fire extinguishers become “hard time components” and are replaced based on stated limits.

Condition-limited parts. This means that the part must meet certain performance specifications, or “condition” standards, to remain in service. An example is a tire, which has a highly variable service life depending on usage and storage conditions.

Rather than get wrapped up in semantics and regulation wording, I’m just going to use time and/or condition. For most of us flying small aircraft, the condition will be the biggie.

Fuel and fuel lines. If you’ve read any of Ron Wantajja’s accident statistics surrounding small aircraft, you know that fuel and fuel systems account for over a third of the mechanical-related homebuilt accidents. The condition of the fuel and the condition of the transport system including valves, vents, and filters all play a part.

What to do: Does the fuel line you are using have a recommended replacement interval? The manufacturer will be able to tell you, and it should be in the maintenance manual. If you don’t have that information, then find out from the manufacturer and add it to the manual.

If you’re using automotive gasoline, aka autogas, how long do you let it sit in the tanks? What grade is the fuel? Does it have ethanol in it?

Hoses. This includes plastic hoses, rubber hoses, automotive hoses, aircraft hoses such as Aeroquip, stainless steel covered hoses, and Teflon hoses.

What to do: If you’re building, don’t use a hose that is not brand new. Hose life is time limited because rubber and plastic break down naturally over time. Check with the manufacturer to determine replacement intervals. Teflon (PTFE) hoses with a stainless steel covering, such as Aeroquip 666 and Stratoflex 124, have no life limits, but they are expensive. The decision will depend on your project.

Flexible line inspections may save you from an in-flight failure. Look carefully at the fittings. Over time, hose clamps can create a weak area that begins leaking slowly. Also, inspect the routing of all lines for chafing.

Cables and push-pull wires. An alarming number of surprises come from push-pull wires on production aircraft. The carb heat and mixture controls are particularly susceptible. These wires tend to vibrate and chafe until one spot becomes so thin it breaks — in flight of course.

What to do: Include control cabling and wires in your checklist at condition or annual inspection time. The wire should be pulled out and examined. Any chafing, abrasion, or thinning is a signal to replace.

Of course, we have a range of other time- and condition-limited parts from batteries to belts, filters to seals, gaskets to spark plugs. Take note of these in your maintenance manual and make sure all inspections are thorough.

* *

Avoid surprises. Depending on what type of aircraft you own, rely first on the manufacturer and the documentation that came with your aircraft. If you assembled a plansbuilt aircraft, you may need to methodically assemble maintenance information on each component as you document the installation.

If you are fortunate enough to have assembled a kit with great documentation, then it will be easy to pick out the potential surprises for time- and condition-limited items.

If you’re flying a production aircraft, the work has already been done for you. Your pilot’s operating handbook and maintenance manual will be clear about time- and condition-limited parts.

If an engine has a TBO (time between overhauls), does this mean it’s a time-limited part? No. It’s a condition-limited assembly with recommendations from the manufacturer. Many well-maintained engines survive safely past the recommended TBO. Sailing past a TBO will require rigorous inspections, lots of attention to data (think oil analysis, engine monitor trends, etc.), and, of course, attention to the time- and condition-limited accessories.

If you fly an ultralight or two-stroke engine aircraft, pay particular attention to the quality of the fuel, the storage conditions for the fuel, and the condition of the plastic and rubber fuel lines. Make a list of the things you think are going to need replacement, based on condition, in the next six months. Some materials deteriorate quickly depending on the environment.

If you fly a homebuilt, take a look at your maintenance manual and your checklists. Identify any items that you think are high wear, high maintenance, or might deliver a surprise. Flag these items for extra attention on your condition inspections. You may need to do interim inspections depending on what you list. Because there is no typical homebuilt airplane, you will need to do this based on the information you have and the information that the manufacturer has given you. Experience from your fellow builders and flyers will also be helpful.

Identifying potential surprises now will save you from identifying them in the air later.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911, is a manufacturing engineer, A&P, EAA technical counselor and flight advisor, and former DAR. She built and flew a Pulsar XP and Kolb Mark III, and is researching her next homebuilt project. Lisa’s third book, Dream Take Flight, details her Pulsar flying adventures and life lessons. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com and learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com.