By Budd Davisson, EAA 22483

This piece originally ran in the June 2021 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

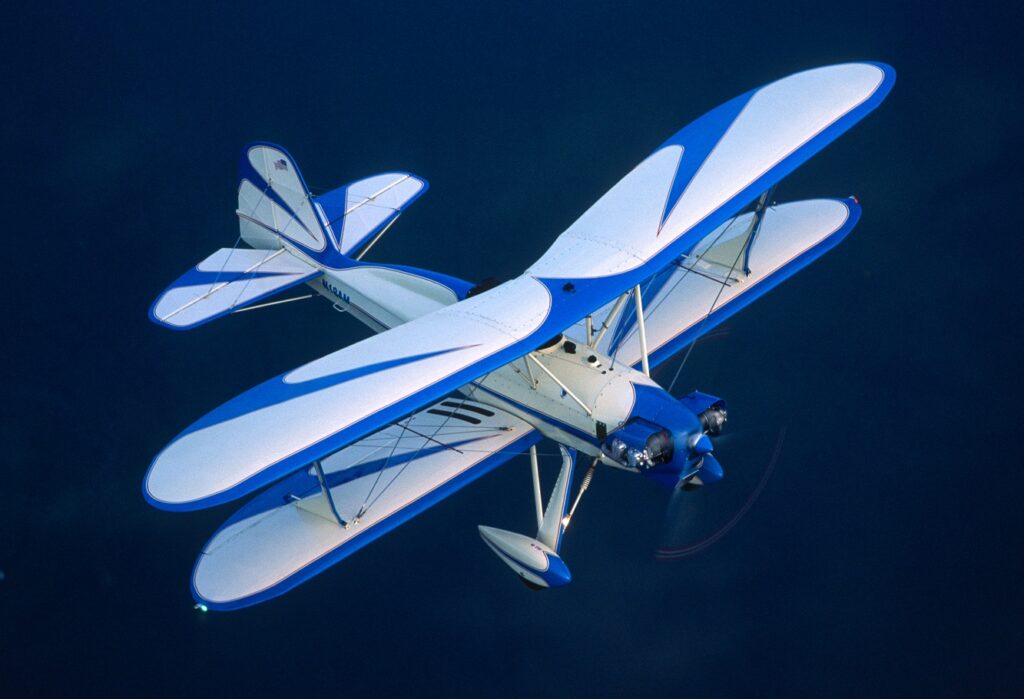

Is there such a thing as the perfect biplane? Is there such a thing as a perfect airplane, period? The answer is a resounding no! This is because there is no such thing as a concise definition of “perfect.” The definition is totally dependent on who is doing the defining. What one pilot thinks is perfect may be totally repugnant to the next one. This is definitely the case when comparing homebuilt biplanes, each of which has its own personality. So, when selecting which biplane to buy or build, both the pilot and airplane personalities have to be considered so the relationship is a pleasant one.

Why a Biplane?

It would be easy to counter the question of “Why a biplane?” with another question: “Why not a biplane?” Let’s face it, there are few pilots who wouldn’t like to at least sample the biplane experience. And the attraction is more than just the open cockpit. Subliminally, pilots know that the airplanes of today evolved from the airplanes of yesterday — and many of those were biplanes. They were centerpieces of the birth of the aerial adventure when we were not only finding our way to a destination, but aviation, as a whole, was finding its way to its future. Biplanes are where it all started. Every pilot knows that, and most appreciate what that represents. And many want to experience it. A word of warning: Do not take a ride in a biplane of any kind if you don’t want your commonsense overwhelmed by the urge to buy or, better yet, build one.

The really big question is: “Which homebuilt biplane will suit you best?” There is a wide range of types, each with widely varying handling, capabilities, and costs. So, the first task at hand is working out a plan of attack that culminates in having a two-winged wonder in our hangar.

Pick a Purpose: Defining the Mission

If we feel ourselves sliding into buy-or-build-a-biplane mode, we first have to decide exactly what we want to do with that airplane. When scanning through the homebuilt biplane catalog, we have to decide what we expect of the airplane and what the airplane will expect of us.

Cross-Country Importance: Normally, “biplane” and “cross-country” are not put in the same sentence, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be used for trundling across the landscape. It just depends on how far you want to go when you want to get there, and how comfortable you’ll be on the way. As a class, biplanes are generally slower than similarly powered “normal” airplanes, but that doesn’t mean that some of them don’t have some speed in their soul. Depending on the power, a Pitts, for instance, can be pretty fast at 150-plus mph. However, hang 1,000 hp on a Hatz and it still won’t be fast. They are polar opposites in a lot of categories.

Aerobatic Capabilities: Every biplane discussed here is capable of the loop/roll/spin type of sedate, “civilized” aerobatics. Some do those maneuvers better than others, and a few specialize in that kind of three-dimensional frivolity. The differences are wide. Aerobatics in a Hatz, for instance, is waltzing with your grandmother/grandfather. Aerobatics in a Pitts/Skybolt is breakdancing with a mongoose that’s had too many cups of coffee. The nerve and skill of the pilot are the only limitations. Those airplanes even convert gravity into a temporary inconvenience.

No-Sweat Fun: No-sweat fun is defined as climbing into your airplane when you haven’t flown for a while and there’s a decent crosswind, but you don’t have to worry about it because the airplane will take care of you. This is another area where the birds can differ tremendously. Some biplanes are simple to take off in and land while others — well, they aren’t.

Cockpit Comfort: Being homebuilts, the experimental amateur-built (E-AB) biplanes are generally much smaller than “real” biplanes of the antique persuasion. However, some E-AB biplanes are bigger than others. A Skybolt, for instance, dwarfs a Smith Miniplane. And the pilot who might be folded up like a cheap pocket knife to squeeze himself into that Miniplane will rattle around in the Skybolt’s spacious cockpit. If your size casts any doubt on your “which biplane” decision, don’t build or buy any aircraft that you haven’t tried on for size.

Kit- or Plansbuilt?

As common as quick-build kits are in the homebuilt marketplace, that’s how rare biplane quick-build kits are. The closest you’ll come to a quick-build kit in the biplane community is the Christen Eagle. Others are supported by companies such as Steen Aero Lab, and partial kits and components are available through those companies, but other designs only exist as rolled paper and you build your own. However, many plans-only airplanes do have suppliers behind them that will weld fuselages, mill spars, etc.

Without exception, all homebuilt biplanes are built the same way biplanes of all types have been built for generations. All are a rag and tube fuselage with fabric-covered, wood-structured wings. As homebuilts go, they are among the least complex airframes, but they have more parts simply because they have more wings. However, wire-braced construction means that any alignment issues can be rigged out by tightening this wire and loosening that one. Also, tubing construction moves along quickly at the beginning but then slows down as a bazillion tabs and fittings demand your attention, and it slows even more when putting on the fabric and painting it. If you’re doing it all yourself (no already-welded components), it’ll take 20-30 percent (that’s a pure, albeit educated, guess) longer than a comparable-sized monoplane.

Buying a Used One?

There is a steady market for biplanes with the more popular ones like Pitts, Skybolt, Eagle, and Starduster Too showing up consistently on Trade-A-Plane.com or Barnstormers.com. Over the half-century since they debuted, lots have been built. In every case, they’re amateur-built, which means they require careful inspecting to determine the build quality. At the same time, it has to be recognized that many homebuilts show craftsmanship that may be far better than factory-built aircraft. However, a few will be less than perfect.

Something we’re seeing quite often recently is older homebuilt biplanes that may have been quality airplanes back in the day resurfacing after long-term hibernation in barns or rural hangars. In these situations, an old axiom applies: “The only thing harder on an airplane than flying it is not flying it.” An airplane can sit in a wonderfully protected, museum-like environment, but the years will still take a toll on it. Unfortunately, many of these finds have not been kept in a museum environment, and tales abound about what buyers have found in recently purchased survivors. The damage runs from mice destroying steel tubing with their potty habits or eating rib stitching to moisture doing what it always does to wood, steel, and the insides of engines. Lycomings especially deteriorate unless properly pickled. So, tread carefully when considering an older or seldom-flown airplane.

About That Tailwheel Thing

In case you haven’t noticed, you don’t see many nosewheel biplanes. As in almost none. However, Waco did build a few of its “N” series cabin airplanes before World War II as nosedraggers, and rarities like the Durand Mk V will pop up here and there. So, like it or not, if it has two wings, it’s all but certain to be sitting with its tail on the ground. This is not a bad thing. It just requires an easily learned skill, the level of which changes from homebuilt biplane to homebuilt biplane. Some are super easy to fly and a few require that the pilot pay some extra attention to what’s going on when landing. We’ll touch on that in each of the pilot mini-reports below.

The Biplane Shopping List

What follows are thumbnail sketches of the most common homebuilt biplanes. If you’re an aficionado of the breed, you’ll note that a few reasonably well-known designs are not listed in the main file. We’ll include those in an honorable mention section. And if we miss any, we apologize.

Acro Sport II

Paul Poberezny and several engineers designed the Acro Sport II as an airplane that can be built and flown by anyone. Structurally and functionally, it is simple. A lot of thought was put into making the structure as easy to build as possible — but there will be a fair amount of welding involved. It carries two people comfortably and is only slightly harder than a Citabria or something similar to take off and land, although it is blinder on the runway. A good checkout could involve power-off landings from the back seat of a Citabria. A Cub is too slow and too easy. It’ll cruise at around 120 mph with 180 hp. Material kits are available from Aircraft Spruce & Specialty, and plans are available from:

Chris Kinnaman

Acro Sport Inc.

P.O. Box 462

Hales Corners, WI 53130

Telephone: 414-529-2609

Christen/Aviat Eagle

Here’s a flat statement that is going to be hard to prove but even harder to contradict: The Aviat (which is the same company that builds the Pitts Specials and Husky) Christen Eagle kit is possibly the most complete, highest-quality, best-produced kit for any homebuilt airplane. The instructions and support literature are mind-bogglingly complete, and the components are even better than FAA-certified quality. There is no welding required. The wings come knocked down and ribs have to be made, but the required jig is included. The company has thought of everything but a thermos for your coffee. It also has to be the most expensive kit because of all the foregoing factors.

Essentially, the Christen/Aviat Eagle is a slicked-up, modified version of the factory-built S-2A Pitts Special and uses the same 200-hp AEIO-360 Lycoming. If looking for a serious, two-place aerobatic biplane, this is the gold standard in homebuilts. It has a larger-than-normal cockpit, and the canopy makes for very comfortable 150-plus mph cruising. The controls are light, and the airplane is quick when compared to most biplanes. This is a good thing. Takeoff and landing require a little specialized training because it touches down faster than most biplanes (but not all). The spring gear makes directional control a little easier than its Pitts Special brethren. You’ll find them listed for sale consistently on Barnstormers.com or Trade-A-Plane.com. Find information on plans and kits at AviatAircraft.com.

Hatz

Where the Eagle is a finely trained German shepherd, the Hatz is a wonderfully lovable cocker spaniel puppy with a huge, nose-licking personality. It might be considered a modern, smaller rendition of a 1930s classic of some sort. It is blacksmith-simple to build, but as stated before, there are a lot of parts. It is also probably the simplest biplane to fly. It isn’t significantly different than flying an Aeronca Champ from the back seat. It benefits when built light with a medium-sized engine, 115 hp, although it’ll take up to 150 hp. It’s a bigger airplane than most homebuilts, which means it also has slightly bigger cockpits. However, it is slow, meaning 80-100 mph cruise. It’s a great hamburger-getter, but not so great for visiting grandma on the other side of Texas. You can find plans at HatzBiplane.com and materials info at Aircraft Spruce & Specialty.

Pitts Special

With the exception of a rare variant of a factory-built kit, the S-2E, all homebuilt Pitts are single place, and they range from 100 hp (rare) to 160 hp (super common and a great combo) to 180 hp (an absolute rocket ship). It comes in two basic versions, S-1C (flat wing, two ailerons) and S-1S (symmetrical wing, four ailerons), both of which are the standards by which aerobatic capability is measured. They also have the biggest reputation on our biplane list for being a challenge to land, which is mostly a myth based on rumors, not fact. However, of the biplanes on the list, it is the one for which some specialized training is most required to prevent unpleasant episodes during the first few hours of flight. This applies almost regardless of what kind of tailwheel time you have or what you’ve been flying. It is not your granddad’s biplane. However, it is the most exciting of the biplanes out there and will put a smile on your face that’s difficult to remove. You can find plans for the S-1S at AviatAircraft.com, and plans and kits for the S-1C and S-1SS at SteenAero.com.

Miniplane

The Smith Miniplane was one of the first homebuilts to gain popularity in the 1950s. It continues to be popular today because it’s small, so it requires less material and will provide lots of fun on 85-115 hp. It’s also easier than some others to build. It’s middle of the road in terms of landing difficulty but does require more experience or specialized training because it can be a little quick on the runway. No dancing on the rudders permitted! Landing a Luscombe in a hard crosswind would be good training, while a few hours in a Pitts S-2 would be the ultimate training. Learn more about plans for the original model by calling Scott “Sky” Smith at 515-289-1439, and find plans and kits for the upgraded Smith Miniplane 2000 at SkyClassic.net.

Steen Skybolt

Lamar Steen, the Skybolt designer, was a big guy and designed his airplane to his measurements. For that reason, this is the choice for someone with larger-than-normal dimensions wanting a two-place biplane. It is easier to land than a Pitts (usually) and gives almost the same performance but requires bigger engines to do that, 180-250 hp. It has the same Curtis Pitts patented airfoil and wing design as the Eagle, the S-1S, and all factory-built Pittses. It is no harder to build than any of the others, but its significantly larger size needs more room and finances. Find plans and kits at SteenAero.com.

Starduster Too

Year: 2000

Lou Stolp’s Starduster Too was possibly the first practical two-place biplane offered to the homebuilder. It was designed in the late 1960s before any other two-place homebuilt biplanes had appeared. Where the Pitts/Skybolt/Eagle have modern aerodynamics, the Starduster Too is traditional in its aerodynamics. This translates to higher drag on approach and in flare and nearly flat bottom wings that compromise its aerobatics. However, the airplane was not designed to give competition aerobatic capabilities. In fact, at some point, when more of them were built and were out there flopping around, Stolp revised the plans to beef up a few points, including the tail. It is in the middle when it comes to takeoff and landings — not as demanding as a Pitts but close. Find plans and kits at Aircraft Spruce & Specialty.

Honorable Mentions

All of the below biplanes deserve to be mentioned, and plans or kits/components are available. Google knows where they can be found.

Acroduster II: Smaller than the other two-place homebuilt biplanes, the Acroduster II generally has a slightly higher wing loading than the rest. It’s about even with the Pitts in terms of landings with a little less aerobatic capability. Few have been built, and its front cockpit is small.

Baby Great Lakes: With only a little over 16 feet of wing, the Baby Great Lakes is easily the smallest of the homebuilt biplanes, and given the small horsepower (65-85), it is easily the most surprising in terms of performance. Definitely not an ideal airplane for bigger body types, it works you just a little on the runway but is a big bang for the buck.

Little Toot: A survivor of the 1950s EAA founding period, the Little Toot isn’t little when compared to the Miniplane, which came out at the same time. It’s more complex than others of the period to build but still is a good flying airplane.

Raven: The Raven borrows heavily on the Pitts S-2C that Aviat is still producing. With 260-300 hp, it’s a mind-blower and is capable of maneuvers most pilots can’t imagine. Only a few have been built.

Skyote: The Skyote (pronounced Sky-oh-tee) is not only the most complicated biplane on the list (the wing structure is fabric-covered aluminum) but also delivers unexpected aerobatic capabilities. It’s a baby Jungmeister! Fortunately, a lot of the parts are available precut and prewelded from various suppliers. It has been overlooked by too many would-be biplane pilots. Better yet, it’s light-sport aircraft (LSA) compliant.

Stolp V-Star: The Stolp V-Star is an LSA biplane that should have been a hit, but for some reason is seldom seen. It is simple to build, and besides being cute as a bug, with 65-85 hp in the nose, it is simply a blast to fly and lands like an Aeronca Champ. This would be a great retirement project for almost anyone who has to build on a budget but wants an extremely pleasing little airplane.

Budd Davisson, EAA 22483, is an aeronautical engineer, has flown more than 300 different types, and has published four books and more than 4,000 articles. He is also a flight instructor primarily in Pitts/tailwheel aircraft. Visit him on AirBum.com.