By Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the November 2021 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

“That was the best AirVenture ever,” Sally said, putting the last duffle behind the seats of the Sonex.

“Totally agree, and I’m amazed at the spirit of it all,” Greg said. “That’s what happens when you miss a year. Like anything else you love, it makes your heart grow fonder.”

“I don’t know if we can fit everything in the airplane,” Sally said, rearranging the bags for the third time. “If my 172 had been out of the paint shop a week ago, we would have flown that.”

“Not as much fun as this 40-pound baggage weight limit,” Greg said, patting the side of the Sonex. “Look, you forgot to pack the cooler.”

He pointed behind the airplane.

“Well, I guess that’s going in your lap,” Sally said, laughing.

The trip home was uneventful. After landing, Sally asked Greg to taxi over to the paint shop.

“I want to check on Blue Streak.”

“Blue Streak?”

“She flies fast.”

Greg shook his head.

Sally was relieved to walk into the tiny air-conditioned office. Tony looked up from his paperwork.

“Hey! How was OSH?”

“Great. Wish we could have taken Blue. We had a devil of a time packing the Sonex for a week.”

“Just shows you how amazing that little airplane is. Well, we’ll be done with reassembly on your 172 midday tomorrow.”

“Can’t wait!”

The next day Sally walked over to the paint shop. Her 172 sat outside, gleaming in the afternoon sun. From nose to tail, the bright marine blue color and precision of the white stripe edges were amazing. The airplane looked brand new. Sally was overwhelmed. Tony came out of the office.

“Wow. I had no idea it would look this factory fresh!”

“That’s what we do,” Tony said with a broad smile.

“It only took four weeks, too,” Sally said. “I guess that’s good — but it felt like four months. I’m almost glad it wasn’t ready for AirVenture. It looks too nice to camp with.”

“We went over it with a fine-tooth comb, Sally. But you should do an extra thorough preflight before you take any trips. We’re human, you know.”

“Right.”

After a cursory preflight, Sally got into the airplane to taxi it back to her hangar.

“I’ll do the extended preflight there,” she said to herself.

The 172 started right up, and Sally started off for the hangar. As she taxied closer, she straightened up in the seat. Suddenly the seat slid backward, too quickly for Sally to keep her balance. She felt herself falling to the rear. In a panic she grabbed the yoke and the side of the passenger seat, trying to get her feet back on the brakes. The airplane continued to taxi straight toward the open door of the hangar. She leveraged herself toward the panel and cut off the ignition switch and pulled out the mixture. The airplane came to a slow stop at the hangar entrance. Sally opened the door, wide-eyed, and then took a deep breath. She looked at the seat, now all the way back in the track. “Where’s the locking pin? Good gracious, it’s a good thing I didn’t just decide to go flying,” she said aloud.

* *

If you fly regularly and often, then your preflight is standardized and routine. You’ve gotten to know the airplane well, and you always check the same things. There’s nothing wrong with this process — unless there’s something amiss in an area you didn’t check.

If you fly often, it is rare for there to be something unusual in an area you didn’t check. All of that changes if the airplane goes in for any major service, any upgrades, any new equipment installations, or if you have to stop flying for some reason. A simple preflight is no longer adequate. Here are some of the traps to look out for when returning your airplane to service.

Return From the Paint Shop

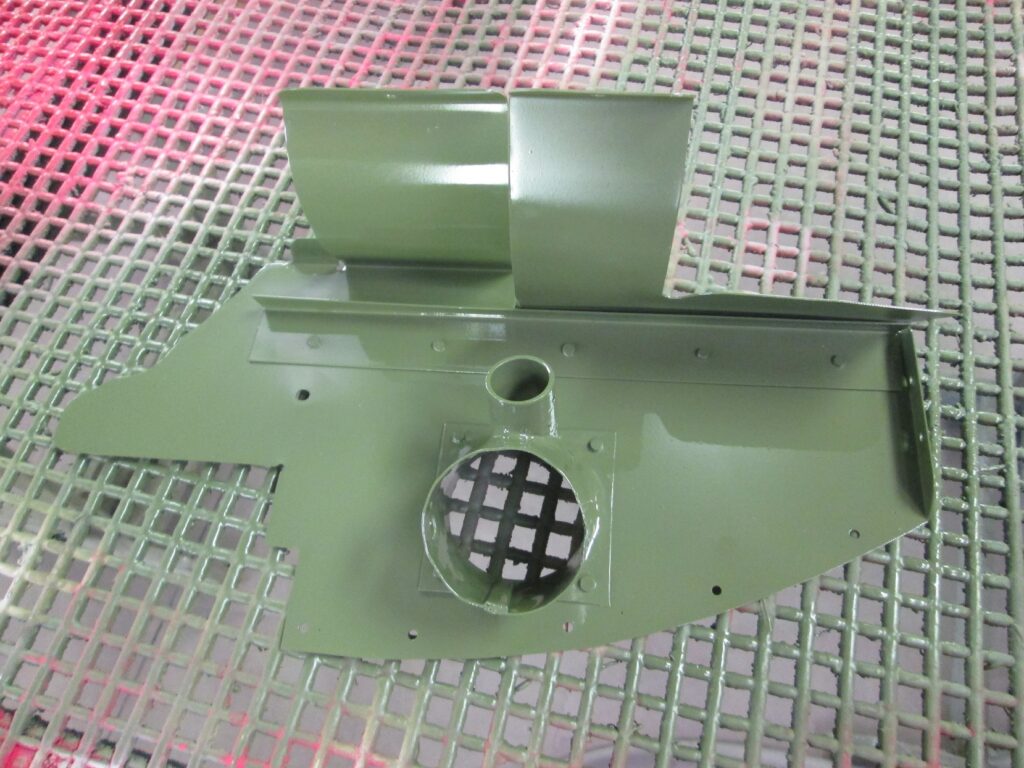

The first thing to check for are things that are missing. I know “things” is a vague term, but the things that are missing can range from nuts, bolts, cotter pins, and safety wire to vacuum system tubing, seat belts, and antennas. The solution to this trap is to have a detailed inspection checklist for your specific aircraft and to take dozens of detailed photographs before you take the airplane to the paint shop. No matter how attentive the shop is, there will be things that are missing, out of place, and not tight.

Use the checklist and the photos to go through all of the systems slowly and carefully when you get your airplane back. Having a friend help you is an advantage. They can read from the list while you look at the items and the photos to confirm that parts are there and the assembly is correct.

Whether you can find everything that is missing or not will depend on your checklist and your patience. More is better. It’s easy for us to miss something if it’s not on the list. Pay particular attention to the following items.

- Fasteners not torqued. It’s time-consuming, but you should go through your list and identify all fasteners and if they are attached correctly and tightened to spec. If you don’t see torque seal, I’d methodically apply it after checking. It takes a lot of time now, but it will save you time later and provide peace of mind.

- Tape, overspray, and vents. There will be tape left in places, and some component edges will have some paint on them. Operate everything that has a hinge, and open and close everything to find any binding. If your paint shop was really pro, they will not have painted over fasteners. But it happens.

- Check all fuel and air vents and any gaskets that go with caps. Missing gaskets can allow fuel to leak out, sight unseen.

- Make sure placards have been reinstalled. Check the fuel selector handle. If it was removed, it could be reinstalled pointing the wrong way.

- Control hookups. You’ve heard the stories of controls being hooked up backward. It’s rare, but it does happen. It’s exceptionally dangerous if not caught before flight. Make sure trim tabs are rigged the right way. For some reason, the mechanics putting things back together are so worried about this that they get it right and then decide they made a mistake and reverse it.

Return From an Annual or Condition Inspection

Any maintenance you or others have done on the airplane introduces the opportunity to make things worse. I think of it as going in for elective surgery to improve something and you end up with an infection and being worse off than when you went in. Mike Busch, an engine expert, calls this maintenance induced failure, or MIF. What this means for any return to service is an extra vigilant inspection before you go flying.

Pay attention to hardware and components not being safetied, loose hardware, and proper torque. Check to make sure wiring harnesses are bundled properly and secured against vibration. Then check everywhere for miscellaneous items, like tools left in the airplane. And finally, check cable and control attachments and travel.

Your preflight should be as thorough as you can make it. If you can find a friend or an A&P mechanic to put another set of eyes on the aircraft, that’s a good idea. When you make your first flight after extensive maintenance, stay in the pattern for 15 or 20 minutes and then land for an inspection.

If all this sounds like overkill, just ask the folks who were surprised by something unexpected.

Return After New Equipment Is Installed

Avionics retrofit? New seats? Panel upgrade? New interior? These are all reasons to pay extra attention before flying.

Avionics. New or refurbished avionics installations may require quite a bit of disassembly in the engine compartment to run harnesses through the firewall and in the cabin behind the panel. Before flying, do extra checks as a part of your preflight for fasteners, wiring bundle integrity and neatness, and that all access panels have been reassembled and that they are firmly attached.

Make sure radios are locked in their trays. Pull to be sure. One owner of a Cessna 210 took off after picking up his airplane from the avionics shop and the radio slid out and blocked the yoke’s forward movement on takeoff. He smartly reduced power enough to provide a shallow ascent. Patiently waiting for a safe altitude in which to maneuver, he pulled the yoke back and quickly removed the radio. He then returned to the avionics shop to get it properly secured. The shop manager was horrified.

Before flying, read and study the information that came with the avionics. Did the shop calibrate it, or is that your responsibility? Find out. If you need help, get it before you fly. No matter how excited you are to get in the air, electrical and avionics problems can cause a serious in-flight emergency. A miswired autopilot or instruments that read incorrectly can be overwhelming and dangerous, even if you are highly experienced.

Equipment such as seats or seat belts, headliners, and panels should be checked for tightness and security. Large items detaching or seats that fall out of their track or are not properly pinned can cause havoc.

Return After a Long Time Idle or in Storage

This situation is far more predictable than the scenarios above. That’s the good part. The difficult part is identifying what deteriorated, how much damage there is, and what critters — from mice to birds to wasps — got in to set up house.

How long? The amount of time the airplane has been idle will drive what you check. And if your airplane uses autogas or a gas/oil mix, fuel deterioration can cause starting and running problems even with a few months of not flying.

Short storage times can cause more problems than planned long-term storage. This is because we know what we have to do to formerly store the aircraft — for winter for example — and we have a set checklist for putting the airplane into storage and for taking it out. But shorter no-fly time periods are usually a result of thinking you are going to go flying but then something comes up to interfere with your plans. These are the situations when you need to keep track of how much time has passed.

The three traps I see most often in short-term storage — what I would call unintended storage — are fuel problems, battery problems, and critter problems.

If your aircraft uses avgas, then the fuel itself won’t be a problem. What you do want to check is fuel hoses and connections for leaks and cracks. If you use autogas, I wouldn’t leave it sitting in the airplane for more than eight to 12 weeks. Yes, that means draining it and using it in your tractor or truck.

If you don’t fly your aircraft regularly, invest in a good aviation-specific smart battery charger. The smart chargers will give you some indication of battery health so you don’t get stranded somewhere and will maintain it between flying adventures.

As for critters, before you fly make sure you check all the little nooks and crannies in your airplane when going through your preflight. Take covers off, use your nose to identify signs of animals making your airplane their home, and take extra precautions with fabric-covered airplanes. Mice love rib lacing, and you’ll find it all curled up in pieces in their nests inside the wings.

Returning an aircraft to service doesn’t have to be an ordeal if you are ready with time, good eyes, and checklists. Extra time on checks and inspections on the ground can prevent shock and panic in the air.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911, is a manufacturing engineer, A&P, EAA technical counselor and flight advisor, and former DAR. She built and flew a Pulsar XP and Kolb Mark III, and is researching her next homebuilt project. Lisa’s third book, Dream Take Flight, details her Pulsar flying adventures and life lessons. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com and learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com.