By Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the December 2021 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

“I decided,” Roy said.

“Decided what?” Kathy asked as they walked back to the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh campground.

“How we will choose an airplane to fly.”

The sounds of flying aircraft mixed with the smell of brats and burgers from a line of eateries nearby blended in with a refreshing cool breeze as the two walked into the shadows of the trees.

“I liked that white and blue Cessna 150,” Kathy said. “The price is right. I’m amazed at how many aircraft are for sale this year.”

“Many of the owners want something bigger,” Roy said. “I don’t want bigger. I want smaller.”

“How do you get smaller than a 150?” Kathy said.

Roy grinned and chuckled. “Here, come sit down a minute.”

They sat down on a bench under a tree. “Here’s how. I’ve decided to buy a kit and build it,” he said.

“You’re kidding me,” Kathy said, surprised. “It will take forever.”

Roy laughed and shook his head.

“I spent a long time today looking at kits after we toured the other aircraft,” Roy said. “When you build, you get a lot of value for the money. You can maintain it yourself, everything is new, and performance is excellent. You can make all the decisions about what you want, and you can get up-to-date accessories and instruments.”

“I’d think twice, Roy. Building an airplane is a big undertaking.”

“I know,” he said. “I’ll choose carefully. There are a bunch of discounts and deals if we buy now.”

“Okay. But please think it through. You never finish anything.”

The kit arrived three weeks later. Roy had it delivered to his father’s house across town. In the first month, Roy was there every weekend and nights trying to sort out the multiple pathways of inventory, task arrangement, and timelines.

“This isn’t quite what I’d envisioned,” Roy said one night over dinner about two months into the build.

“I was afraid you’d say that, but not so soon,” Kathy said.

“Well, it would have been better if we’d had the space here. Then I wouldn’t be gone so much. Dad doesn’t mind me using the workshop, but every time I turn around, I need something he doesn’t have, like a vise and a band saw. It stops me in my tracks. And then I didn’t realize I needed to learn some riveting and fabric-covering techniques. I have paperwork all over the place, and I can’t seem to find anything when I need it. You’ve been very patient with me. I appreciate that. It’s too bad you can’t help.”

“My business travel makes it tough,” Kathy said. “That’s why I was hoping we’d get an airplane ready to go, at least now, and maybe build later.”

Roy sighed. “Well, let’s see how it goes.”

Ten months later Roy arrived home clearly frustrated.

“I should have listened to you, Kathy,” he said. “I’m all wrapped around the axle trying to decide what to do with the project. At the rate I’m going, we’ll be 90 years old before we get in the air.”

Kathy turned to look at Roy. “Okay. Can we go look at Cessna 150s?”

“No need. I already located a flying version of the aircraft I am trying to build. I worked out a trade plus some money. The owner wants to build another one.”

* * *

Building your aircraft is one of the most exhilarating experiences you can undertake. But it’s not as straightforward as the kit manufacturers might have you believe. Not all of us are going to be thrilled with the logistics or complexity — and that’s okay. There are many ways to get in the air.

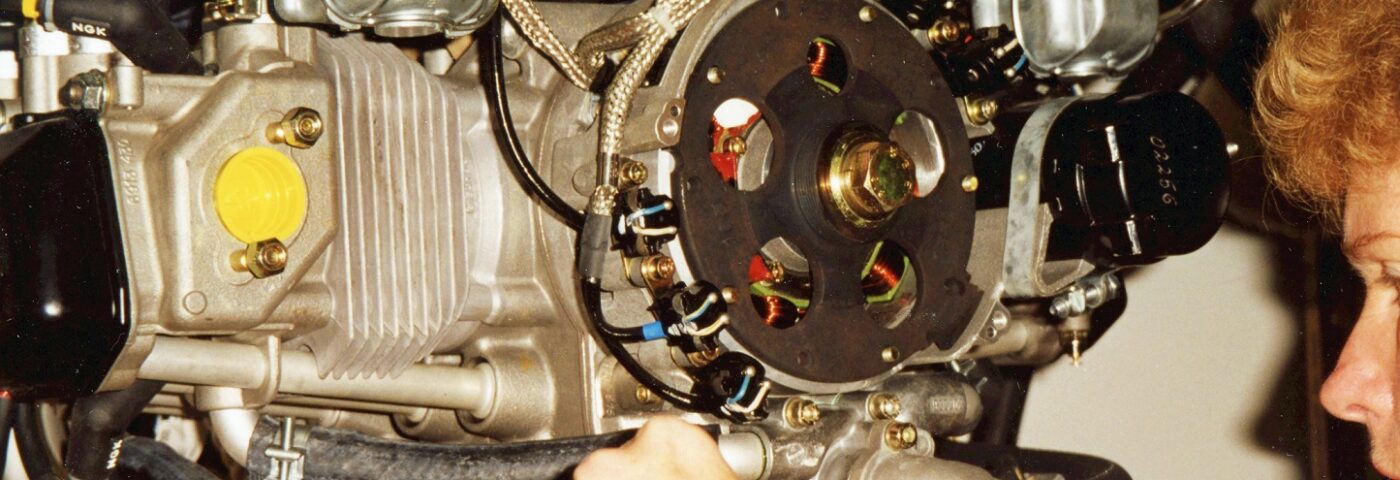

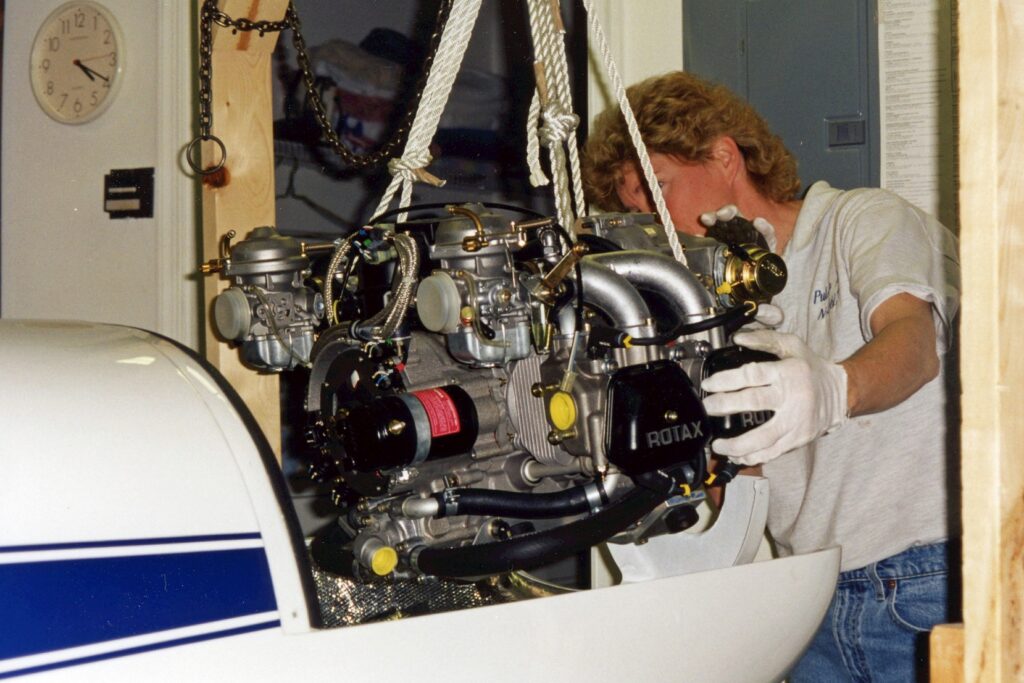

There are dozens of books and articles on how to build an airplane. For a first-time builder, it can be bewildering. Starting my first build in the 1990s, I read everything I could get my hands on. Now, 20 years later, there is a lot more information. It can be overwhelming.

If you want to get in the air in an aircraft you built, I have some suggestions for you that are gleaned from years of visiting projects and coaching builders. You may want to read everything out there; that’s fine and good, but no matter how much information you accumulate, some critical components form the foundation of a successful build. If you are missing any one of the four, your chances of finishing the build and getting in the air are substantially reduced.

Projects stall for a variety of reasons. Funding, workshop space, technical difficulties, not having enough time to keep the project on track, and major life changes are the big ones.

In the last 20 years, completion rates have gone up because manufacturers have done a better job of organizing and documenting their kits, but the statistics are still not what they could be. As a technical counselor, I was always disappointed when I couldn’t help a builder get a project back on track and into the air. But when we were successful, it was a glorious achievement.

Here are the four blueprints or critical items that will drive success. Use all of your other materials — books, articles, and EAA resources — to supplement these four criticalities as you build.

Know Thyself

Are you a builder or a flyer? Do some self-analysis. Are you building the airplane so you will have an airplane to fly, or are you building an airplane to enjoy putting it together? If you think this through and decide that you’re at least 50 percent builder, then you have a much higher chance of being successful. If you realize you are not excited about building, that it is a means to an end, then find an airplane to fly and let others do the building. (See “Technical Difficulties: Are You a Builder or a Flyer?” in the April 2021 edition of EAA Sport Aviation.).

Are you a project person? Do you love tinkering? A do-it-yourselfer? A problem-solver? Fascinated by how things work? If so, you should be a successful aircraft builder.

Do you have some experience with workshop tools? The good news is that aircraft building doesn’t require a lot of tools and equipment. Basics include jigsaw, drills, vise, measuring devices, screwdrivers, and clamps.

Are you patient and methodical? Do you enjoy reading instructions? Yes, some people enjoy reading and following instructions. If you’re the person who throws out the instruction sheet first thing, think twice about building an airplane.

Can you handle adversity? Aircraft projects contain uncertainty and confusing problems from time to time. You’ll make mistakes and have to do some things over. You’ve got to be able to let frustrations roll off, think positively, and regroup mentally. Even major life-changing events can be overcome with perseverance.

Money

I have seen plenty of projects come to a halt because of funding. Even the best planning can result in oversights or situations where you decide to add accessories or make changes.

Once you have made the personal self-knowledge assessment, do some in-depth research on the cost of the build. Where will you work? What tools will you need? What workshops will you attend? What extras will you want? List out the kit costs and add the other items. Then add 15 percent. If you don’t need it, you’ll be delighted later.

Consult with the builders group if the aircraft has one. Ask builders who are flying if they will share build hour times and costs with you, as well as any surprises.

When I built my first aircraft, I took out a loan. At the time it was a stretch, but I’m glad I did it. I would not have been able to get in the air in my own project had I not done it. Realize that if you sell the aircraft later, you’ll be able to get out about what you put in materially. There are exceptions — Van’s RV models are hot now and command high prices on resale.

Systems and Planning

Research your build. Assemble a wish list and narrow it down to three airplane kits or plans. How long will it take? Double the manufacturer’s estimate. When you finish it early, you’ll be delighted. Regular kit or quick-build? Hands-on at the factory? List the pros and cons.

Realize that a scratchbuilt or plansbuilt aircraft will be time-intensive and complex. Make sure you are up for this, especially if it is your first project.

Planning and organizing, along with effective time management, will make your build proceed smoothly and provide psychological rewards. Without systems, the project will become overwhelming. Here are some tips.

Time-block planning. An effective psychological trick. Take the manuals and spend some time “chunking” out times for building. Be generous with your time estimates. Make the work tasks short enough that you accomplish them on time. This takes stress and strain out of the build, and gives you a sense of achievement every step of the way. Allot time for cleanup, inventory, and task reviews (knowing what you’re going to do before you begin).

Disciplined documentation. This means taking the time to do a detailed inventory and organize all of your paperwork. The longer you wait to do this, the more difficult it will get.

Knowledge-priming. Before you begin a task, study up. Read through the steps more than once. When I was building, I made a copy of each set of task instructions and would read and reread them at night before falling asleep. This sounds a little over the top, but I swear by the technique. I’d dream about building during sleep.

Use of Resources

One hallmark of unfinished projects is that the builder never took advantage of free resources to help move the project along. They kept trying to do it all and then ran into a thorny problem that they couldn’t move past. EAA technical counselors are an invaluable resource for builders, as are flight advisors and local airport personnel. The A&P mechanics on your field are usually happy to look things over on your project and even assist you in solving problems.

Builders groups are another resource. During my builds, I got great advice from the folks who had already encountered the problems I was seeing.

The kit manufacturer is also ready to help. Unless you are assembling a kit where the manufacturer has gone out of business, it will be at the ready to answer questions.

Building an airplane is complex and certainly not for the faint of heart. But it’s entirely possible, no matter how complicated and time-consuming it appears, as long as you heed the critical factors.

Do a personal analysis and be honest with yourself. Remember, there are many creative ways to get in the air. A group build is always an option if you don’t want to build by yourself. Plan the money flow so you don’t run out halfway through.

Be disciplined in your knowledge curve, taking enough time to read and/or attend workshops. Let patience be your steady state. Organize your documentation and your inventory so you know what and when you need parts and instructions. Assemble a thorough builder’s log from the beginning. Saying “I’ll worry about that at the end” can bring your project to a halt.

Get help when you need it. Ask questions and have multiple sets of eyes on the aircraft. Use a technical counselor from the beginning and sign up for more than a couple of visits. Find your flight advisor and designated airworthiness representative well in advance.

Building your own airplane will be one of the most fun and most satisfying things you ever do. You will know your airplane inside out. You can do the maintenance and the condition inspection signoff if you get the repairman certificate. Flying your homebuilt into an event like EAA AirVenture Oshkosh will be the pinnacle of realizing a dream come true.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911, is a manufacturing engineer, A&P, EAA technical counselor and flight advisor, and former DAR. She built and flew a Pulsar XP and Kolb Mark III, and is researching her next homebuilt project. Lisa’s third book, Dream Take Flight, details her Pulsar flying adventures and life lessons. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com and learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com.