By Michael J. Martin, EAA 1047599

We all have them. Fat fingers. Some have bigger hands compared to others, but the term “fat fingers” is not just about the size of your mitts. It is about how you use your hands and how accurately you press, flip, toggle, pull, or twist the controls within an airplane while in flight or on the ground.

Now, an airplane in flight is not exactly the best environment to control switches accurately and precisely. You can be in severe turbulence, flying in thick IMC, or even be inverted, hopefully with the purpose and intent to be upside down at that moment.

At a recent coffee gathering of EAA members at our local airport (Buttonville Municipal, CYKZ, north of Toronto), one by one, pilots shyly shared their own fat finger stories. No one ever wants to tell others of their airborne mistakes. However, fat finger problems are a far more common situation than anyone realizes.

First, David spoke about how he was on a training flight in heavy IMC flying an approach in his Cessna 182 with the instructor sitting next to him watching like a hawk his every move and generally observing his nearly acquired IFR techniques. David’s instructor was an ex-airline ATPL flyer with years of experience, so the perfect person to teach David all that he needed to know to earn his IFR rating.

They were doing an IFR cross country trip and on approach to runway 19 into CYGK (Kingston, Ontario). They were in the white with no horizon and no ability to see the ground. At 3,000 feet on final, David began his standard pre-landing checks. Every pilot can automatically and rhythmically sing off the series of checks, “Primer in and locked, master’s on, mags on both, fuel selector on both, mixture rich, etc.” It is all a second nature melody burned into every pilot’s brain.

However, on this day and on this approach David’s fat fingers hit the two rocker split switches for the Master ALT/BAT. He inadvertently flipped both firmly to the off position.

The whole panel went dark in a millisecond. Ouch. Instantly David recognized exactly what he had done and turned the rocker switches back on again.

However, they lost everything. Instruments, radios, VOR, ILS — it was all dead. Of course, the engine was perfectly fine. The instructor asked, “What did you do?” Of course, he knew full well what had happened. And he was ready to jump in to help, but he was not needed.

David handled it all like a pro, even with his rapidly accelerating heartrate from the higher-than-normal rate it had already obtained due to the checkride, but he was able to get a firm grasp on his emotions and rebooted the airplane’s avionics.

He flew the airplane straight and level. He restored power and recaptured the ILS. He failed to make the procedure turn required for the approach, so when the radios woke up and he had reestablished his navigation, he communicated to ATC and explained his failure. He was the only airplane in the pattern, so all was fine. The landing continued and all subsequent events were uneventful.

David reported it all as a powerful learning experience. The priority is always to fly the airplane. David added, “Remain calm, stay cool, have fun.” He added, “Bad things take time to happen, so you have time to recover from them too, so do not panic.”

Next, Simon, EAA Lifetime 1281136, was flying a 182RG. Simon loves his technology and is a precise pilot who uses all the available tools to collaborate with each other to validate data and information. Of course, he has a tablet computer strapped to his right knee and a clipboard strapped to his left knee. He looks like a NASA pilot. He is the first guy to adopt all the latest and greatest technologies and his home is wired to the max — actually, it is wireless. He owns VR headsets, 3D printers, and all sorts of innovative systems. Yes, he still flies the airplane, and uses the technology to assist in the workload. Some might think that all this tech increases the workload. But, not Simon — he loves it all and assures us that it helps keep him and his family safe.

Simon’s moment of Zen happened when he was flying in Toronto’s City Centre airspace in some mild turbulence when a sudden uplift caused by turbulence caused his left leg to slide towards the side wall of the airplane where all the breakers are located. The uplift caused the clipboard to inadvertently flip the avionics master switch off, throwing chaos into the flight. This critical switch has a protection guard on it too. But the clipboard was not deterred, and everything went dark in a blink of an eye. A dead panel.

Diagnosing what was happening and which switches were okay was the next step. It was not too hard to figure out as everything went dead, including the radios. So, the restoration was completed quickly. A cause-and-effect review of the systems to determine what information to trust and to figure out what was wonky took just a minute. He was flying on course and in VMC conditions, so he had the time and the abilities to troubleshoot the situation and restore the systems. The lesson learned is not to use the clipboard in the 182 on the left knee. The ergonomic designs from 40 years ago are rarely a friendly attribute in any airplane.

Radios on Simon’s block-time airplane are Garmin 430/530, so the GPS self-test cycle delayed the radio recovery. Did he miss any critical radio calls in this dense urban location while the GPS recovered? The audio panel was also affected and by default selects Comm 2 upon recovery. But, if Comm 2 is also a GPS combined with a radio, the recovery is also still painfully slow compared to a standalone, single-purpose radio.

The start-up time is about a minute. But time feels so much longer when stress is applied. In Simon’s language of high science and technology, he commented, “The time dilation is caused by special relativity.” Okay, so it felt like it took forever then…

Finally, Mark, EAA 581058, shared what he had learned. Mark is a veteran pilot who is also an instructor and a ferry pilot. He has thousands of hours on dozens of types. Mark has all the ratings.

Mark discussed “buttonology” and “knobology.” Mark offered, in aviation, the terms “buttonology” and “knobology” are often used to describe two different approaches or styles of interacting with the controls and systems in an aircraft cockpit.

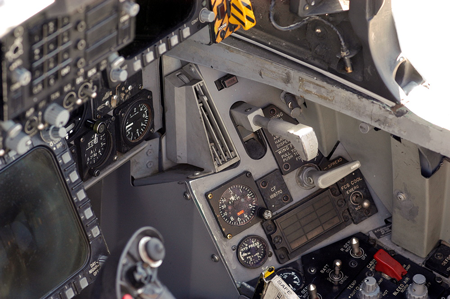

Buttonology: This term refers to a style of cockpit interaction that primarily involves the use of buttons, switches, and other digital interfaces. In modern aircraft, many functions and systems are controlled through electronic displays and panels that feature a variety of buttons and touchscreens. Pilots who are skilled in buttonology have a good understanding of the various buttons and their functions, allowing them to efficiently navigate through menus and select the desired options. They are adept at interacting with the aircraft’s computer systems and avionics using these digital interfaces.

Knobology: On the other hand, knobology refers to a style of cockpit interaction that relies more heavily on physical knobs, dials, and switches. This approach is often associated with older aircraft designs or those that emphasize mechanical controls. Pilots who excel in knobology are familiar with the physical layout and functions of the knobs and switches in the cockpit. They have a good sense of how much force or torque to apply to manipulate the controls accurately. Knobology can be considered a more tactile and hands-on method of interacting with the aircraft’s systems.

It is important to note that these terms are not mutually exclusive, and most modern aircraft incorporate a combination of buttons, knobs, and other control interfaces. Pilots are generally expected to be proficient in both buttonology and knobology to effectively operate the aircraft they are flying. The specific balance between the two approaches can vary depending on the aircraft type and its avionics suite.

In modern airplanes equipped with the Garmin G3000 touchscreen, pilots must anchor a finger to the edge of the panel; they type with their thumb; especially when in turbulence. It is all great during the day, but far more challenging at night. Your visual acuity is impaired at night. It is easy to make a mundane mistake. Mark says to: “Look, enter/type, validate. Do not assume.” At night, it takes three times longer to enter data compared to daytime. Even with the fancy, state of the art Cirrus Perspective G6 G1000 panel with keyboard entry, it is all great, but you need a different level of discipline to avoid fat finger problems. What you learned with steam gauges is different with a modern glass cockpit.

There were at least five more stories of fat fingers that could be shared here. There was a lot of repeated scenarios. But the message is crystal clear. Slow down, think, act correctly. Practice improved situational awareness inside the cockpit, too, to make smarter, more precise, and better command and control decisions. Fit fingers are always better than fat fingers.