By Lorrie Peters

1st Lt. Willis R. Retzlaff (Bill) was born in Antigo, Wisconsin, on May 11, 1918. Antigo is a small rural town, the type where everyone knows each other and the sense of patriotism and love of one’s country runs high. Raised by his parents, both children of German immigrants, the pride of being an American and love of God were part of his everyday upbringing.

His mother, who passed during his time in the war, instructed him to always recite the 23rd psalm before each mission, which he did faithfully.

Lt. Retzlaff joined the Army Air Forces, as many young men did at the time, to fight against a grave wrong and injustice that was happening in Europe. He had always dreamed of being a pilot, and this was the perfect way for him to contribute to the war effort. He was a bit older than most of the other recruits, as the average age at enlistment was 16 to 19 years old. Lt. Retzlaff was 22 years old. Hence the nickname his crew had for him of “Old man.”

Lt. Retzlaff joined the Army Air Forces, as many young men did at the time, to fight against a grave wrong and injustice that was happening in Europe. He had always dreamed of being a pilot, and this was the perfect way for him to contribute to the war effort. He was a bit older than most of the other recruits, as the average age at enlistment was 16 to 19 years old. Lt. Retzlaff was 22 years old. Hence the nickname his crew had for him of “Old man.”

He received his aerial training at Chico, California, and Douglas, Arizona. He transferred to the Air Corps from the paratroopers after previous service in the infantry.

Lt. Retzlaff flew a B-24, an aircraft that, at the time, carried the heaviest payload in the Army Air Forces. The B-24, nicknamed the Liberator, was a long-range heavy bomber used during World War II by the U.S. and British air forces. It was designed by the Consolidated Aircraft Company (later Consolidated-Vultee) in response to a January 1939 U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) requirement for a four-engined heavy bomber. It was highly modern for its day. As U.S. bomber squadrons deployed, the B-24 became the standard American heavy bomber in the Pacific theater due to its longer range. Lt. Retzlaff flew with the 450th Bombardier Group, 720th Squadron as part of the famous Cottontails.

Lt. Retzlaff’s aircraft was often shot at, and more often, shot up. He and his crew would return to their home base in Manduria, Italy, to patch their airplane back up using parts and pieces scavenged from other downed aircraft.

It was February 25, 1944, when during his second raid on Regensburg, the objective being the Messerschmitt plant, that Lt. Retzlaff encountered real trouble of the worst kind. Before reaching the objective, flak knocked out two of his engines. The “Lib” began to fall back out of formation and Lt. Retzlaff, as the pilot, had to make the call. He decided he had better get home to Manduria. Struggling to hold altitude, he jettisoned the bombs. Some German Me 109s spotted his crippled bomber and flew in for a nose attack. “They pressed their attack so closely we could see the features and eyes of the pilots’ faces. It’s a miracle we weren’t all killed,” Lt. Retzlaff said.

Fire from the Germans’ 20 mm cannons had blown out the controls and he ordered his crew to bail out. Lt. Retzlaff looked around as he jumped and saw that all of his crew had gotten out and then watched the airplane crash. The crew, his crew, was scattered all over the countryside.

When he hit the ground, Lt. Retzlaff worked quickly, removing his parachute and hiding it. He began to walk and hide. The country was very mountainous with lush green valleys. Keeping away from cities and villages, he started walking through the woods. Growing tired, he sat down to eat the concentrated food in his kit. It was then, as his adrenaline calmed, that he realized he was injured. His ankle was badly sprained, the pain almost unbearable. He tightened his boot to try to control the swelling. This injury would bother him for the rest of his life.

Luckily he had stopped, for along a path almost directly in front of him marched a patrol of three German soldiers. That night he slept in a barn where he stole three chicken eggs and ate them raw. Because it got so cold, he got an early start the next morning. At the top of a hill, he saw another patrol of five soldiers, and again they almost found him.

About 10 a.m. on his second day, he encountered a huge barbed wire entanglement. On the other side was an open field. Lt. Retzlaff was undecided about crossing the entanglement as his injury made his progress very slow. But he finally did, reasoning there must be someone on the other side, perhaps friendlies. Concealing himself once more, he walked on. As he was looking down on a village debating whether he should go down and try for help or maybe look for food, somebody behind him shouted, “Hey, Hey!” Lt. Retzlaff recounted. “I remember being so tired and so hungry I could hardly think right. I prayed out loud asking the Lord for his protection and guidance.”

About 10 a.m. on his second day, he encountered a huge barbed wire entanglement. On the other side was an open field. Lt. Retzlaff was undecided about crossing the entanglement as his injury made his progress very slow. But he finally did, reasoning there must be someone on the other side, perhaps friendlies. Concealing himself once more, he walked on. As he was looking down on a village debating whether he should go down and try for help or maybe look for food, somebody behind him shouted, “Hey, Hey!” Lt. Retzlaff recounted. “I remember being so tired and so hungry I could hardly think right. I prayed out loud asking the Lord for his protection and guidance.”

Turning around, he saw two soldiers with their rifles leveled at him. He could see by their uniforms that they were not Germans, and realized they appeared quite friendly.

He had quite a time making them understand who he was. When he got it across that he was an American they were very happy! They shook his hands and clapped him on the back. He discovered that they were some of Marshall Tito’s partisans.

They took him to a house in a valley and gave him food and Schnapps, lots of Schnapps! While there, Lt. Retzlaff’s copilot came in. What a happy reunion! After landing, the copilot had also headed south, coming to this same village. He was searching for food in a house where a woman was pro-partisan. She gave him food and directions to the same house.

Marshall Tito’s partisans wanted to take the American flyers to their camp to see their commanding officer. At the camp, the Americans spoke with an English-speaking doctor and were surprised at the way they were handled after the friendliness of the soldiers. He questioned them severely, pulling no punches, for about an hour. Then a big man with bushy hair, apparently the commanding officer, came in and put a few questions to them, treating them again in friendly manner. The doctor apologized; he had thought they were German spies.

Retzlaff and his copilot spent several days in this camp, the partisans urging them to join their cause. But the Americans wanted to try to get back, so with one partisan as a guide and a letter of safe passage from Tito, they set out.

There were many close calls, being strafed and bombed and once chased by a Panzer unit that came over a hill as they were eating breakfast.

Only at night did they attempt to cross the German lines and pass through German-held cities. All the big cities, valleys, highways, railroads, and sizable roads were held by the Germans. Germans were constantly on patrol in armored cars. The Germans also had concealed machine gun nests and fired blindly from those at night.

Once a German bomber flew over his sleeping place and all the men ran out toward the edge of the city, and as they ran, they prayed. “You may not be religious, but when you’re that scared like we were you don’t have to know any prayers, you just pray! And don’t think that every man isn’t scared. It’s only in movies that soldiers are calm and cool. I have never yet seen one that way under fire.”

One of the men was wounded by a bomb fragment. Since the partisans didn’t have any medical supplies, they cleaned the wound with Schnapps, which really only kept the wound clean until they reached their base in Italy.

The native Italians had very little food and there was a great deal of suffering, Lt. Retzlaff reported. The Germans would sweep down into a valley and take all food and equipment, burning fields and homes and villages, anything in their path.

The partisans fed the Americans as well as they could and were very sympathetic but had so little themselves. Most only some bread. Sometimes soups were made with weed and corn meal. “Not very tasty, but it was hot and better than nothing.”

For three months as he went along, people would point out the ruins of their homes and talk of their families now dead, wounded, or captured. He saw the villages completely destroyed by wanton bombing. “When you see the evidence, you understand the bitter hatred these people have for the Germans.” Italy, he said was swarming with kids. And their way of greeting an American was, “Allo, gum?” He met one small boy whose greeting was, “Allo, mitch?” The lieutenant shook his head and said no. “Allo, gum?”

Again, the answer was no… “Allo, Joe,” the boy said in a despondent voice.

Lt. Retzlaff was not alone when he finally reached his outfit in Manduria, Italy. He lays his escape to God, luck, and the great help of Marshall Tito’s partisans. With him at the time of his return were several of his crew. They lectured for two weeks on escape and received a commendation from the commanding officer of the 15th Air Force for the fine job they did.

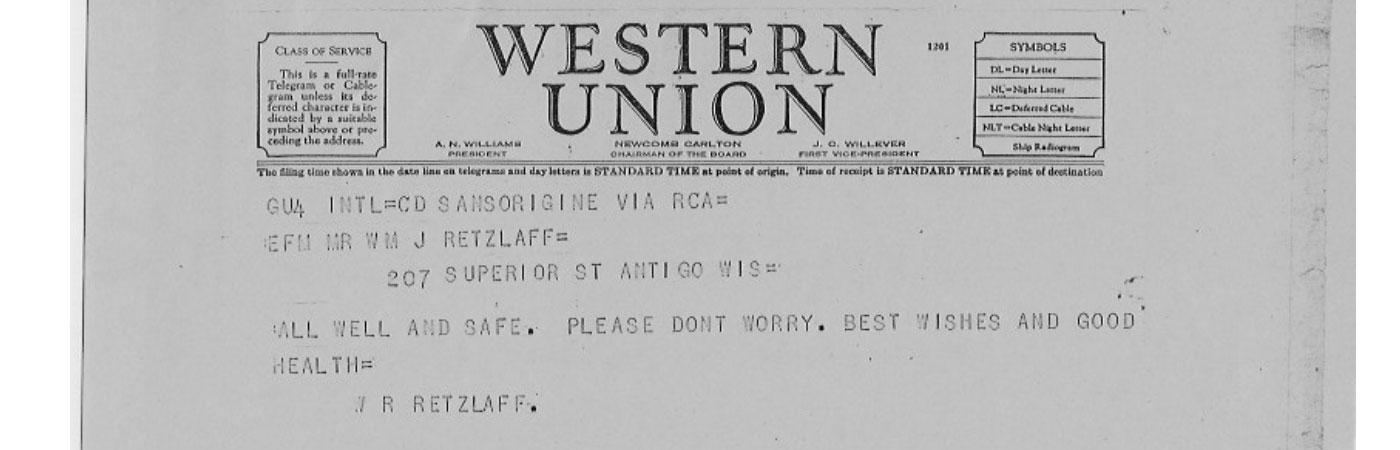

During all this time, his parents back in Antigo, Wisconsin, had only a telegram from the war department saying he had been shot down and was presumed dead. They waited patiently and prayed for three months for news of their son. It was after reaching his home base of Manduria and being debriefed for two weeks that he was allowed to contact his parents. The telegram was brief, it read:

“All well and safe. Please don’t worry. Best Wishes and good health. W.R. Retzlaff.”

They still didn’t know where he was or if he had been wounded.

Because of his uninvited visit behind enemy lines and his subsequent escape, Lt. Retzlaff was restricted from further flying in the European theater. Bill was cycled back to the United States toward the end of 1944. He remained active in the Air Force Reserve until 1953.

During his life, he went on to marry his bride, Iris, and father and raise five children with her. Bill was a very successful entrepreneur, owning and operating a large chain of Ben Franklin stores, craft stores, ladies’ apparel, two banks, as wellas several Hallmark Card and Radio Shack stores. He loved the “thrill of the deal.” His word was his bond, and the finest compliment he could give someone was when he would say “he is a good man.”

Bill and Iris were married more than 66 years. During his life, Bill would often reminisce about his time in the war. During those times he always spoke of Italy and the wonderful people there. His legacy is one of love for his family, love of God, and love of his country. A true patriot and a hero to his family.