By Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the January 2024 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

If you’ve ever painstakingly designed and built furniture, machinery, or a custom home, you’ve probably found one or more errors after the build, despite the detailed planning you did. In that moment, you might have said to yourself, “You can’t find everything.” But it doesn’t have to be that way. As comforting as this rationalization is, it’s possible to get nearly everything right.

The trick to good planning lies in recognizing our tendency to rush a project. We all do it. We want to get it done because we are running out of time, we want to show it to others, or because we need it. We may have a personality that makes it hard to concentrate on the tiny details. Our pre-planning might have been inadequate.

There are many reasons we can end up with something that is not everything we’d hoped for. But once we understand the tendency to under-plan, we can correct it.

If you are building or rebuilding an airplane, success is in the details. The amount of forethought and planning will depend on the type of build. Plansbuilt and original build (where you’re the creator) will take the most planning. Quick-build kits will take the least. But even quick-build kits will benefit from the planning I’m about to talk about.

Spending pre-planning time on the following areas will make a safety and comfort difference once you get in the air in your new or restored aircraft. Add items to the list as you think of them.

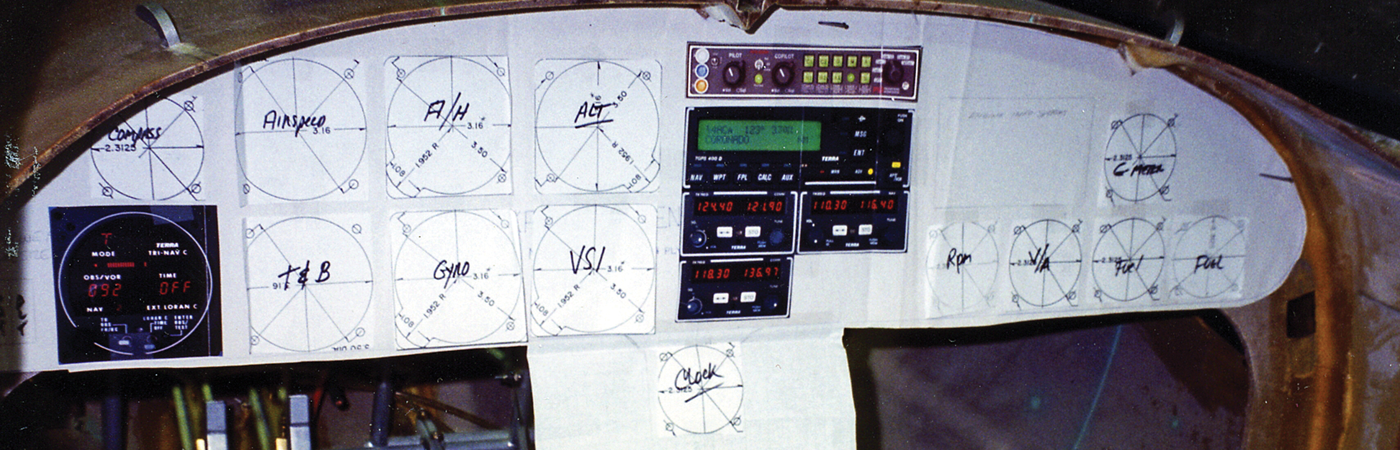

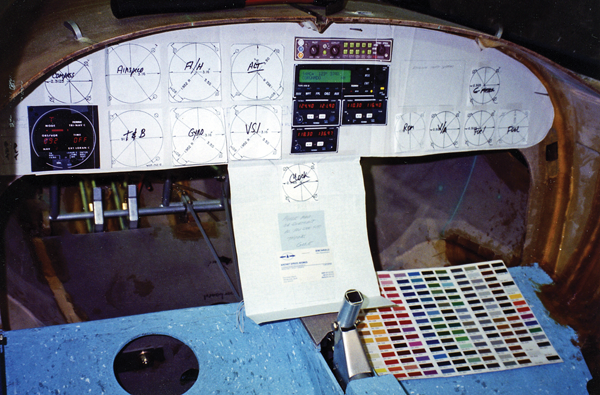

Panel Mock-Ups

Growing up, I read many Tom Swift adventures. Imagining that I was building rockets, I would plan out what the instrument panels looked like. Later, when I got my first car, I added every gauge I could think of. I even installed a nonfunctional set of switches for my nieces and nephews who would play co-pilot and engineer when I drove them home from school.

When I was building my Pulsar, the moment I pulled the step stool over to the fuselage sitting in slings and climbed in, it was heaven. I imagined what the panel would contain. Most important, it was for real.

This is one of the many glorious times during a build — when you get to climb into your half-built aircraft and make engine noises. Invest considerable thought here. You will spend time in the air with what you add, and where you place everything will be critical.

Things left out of reach will be things you find you will routinely need in flight. You’ll have all sorts of ideas when you are sitting there. It’s helpful for the design components and therapeutic for the soul.

For a detailed review of cockpit design planning, read Tom Staggs’ article, “Cockpit Considerations for Homebuilts,” in the October 2021 edition of EAA Sport Aviation.

You should go through this review for restorations as well. Although much of what goes back into a restoration is fixed, there is enough variability from aircraft to aircraft to justify verifying what goes where and making additional decisions. Assumptions here are the enemy.

Angle of Attack (AOA) Indicator

We know the wing stalls at only one angle of attack (depending upon any given configuration), but it can stall at any airspeed. Knowing how much lift is being generated by your airplane’s wings is a great thing to know to prevent incipient stalls. Because loss of control is a major cause of fatalities (especially in that turn to final), why not have angle of attack information? Even the Wright brothers had a rudimentary device made of wood and a piece of yarn.

Early efforts at providing this information to the pilot were complicated because the AOA changes with flap settings, making calibration more complex. If you’re going to have an alert in your airplane, you want it to be accurate.

The other issue around AOA is getting that information to the pilot visually as well as aurally. If you can see your margin to stall in a head-up display, you’ll have the information you need at the same time you are forming your sightlines to landing.

While I will not tell you what to install in your airplane, I will say it’s a great idea to put an AOA sensor in if you haven’t planned for one or it’s not included in your glass panel instrumentation. I recommend doing your own research and deciding. EAA has done considerable work on this, especially through the Founder’s Innovation Prize with the development of Mike Vaccaro’s FlyONSPEED AOA system.

For more information, and a detailed analysis of what an AOA can do, read Charlie Precourt’s “A Progress Check on AOA Systems” in the February 2023 edition of EAA Sport Aviation.

Seating and Belts

When you are working on your panel mock-up and making engine sounds, make sure the seating is what you want. It may be tricky since, in many kits, once the seats go in, they’re not adjustable. In this case, it’s better to build for large people and add padding and cushions later.

Most of us take seat belts for granted as we’re building, assuming any system will do. But there’s variation in quality and fit. Unless your kit already has belts specified for it, I’d make sure you choose a system that is both safe and comfortable. I chose double shoulder strap (“Y”) designs for my airplanes, as it’s the most secure.

One mistake I see on inspections is attaching the shoulder harness to the lower back of the seat. The builder would tell me, “I can’t find any other place to put it.” Think this dilemma through during your planning. Attach points should be structurally sound and even with or up to 30 degrees above the shoulder level to prevent spinal compression in the event of a crash.

If the manufacturer has not provided the structure, or you’re dealing with an older airplane that came with lap belts, identify a solution with the manufacturer.

If you are restoring a certified aircraft, you’ll need to get approval for a seat belt harness retrofit. Here’s what the FAA says:

“A retrofit shoulder harness installation in a small airplane may receive approval by Supplemental Type Certificate (STC), Field Approval, or as a minor change. An STC is the most rigorous means of approval and offers the highest assurance the installation meets all the airworthiness regulations. A Field Approval is a suitable method of approval for a shoulder harness installation that needs little or no engineering. Shoulder harness installations may receive approval as a minor change in certain cases. In such cases, the FAA certificated mechanic who installs the shoulder harness records it as a minor change by making an entry in the maintenance log of the airplane.”

You can find more information via the links at EAA.org/Extras. Also, FAA AC-43.13 2B, page 85, has installation diagrams for belts.

Alerts

You should have warning devices for carbon monoxide and a way to extinguish a fire. Both problems can quickly kill. While a fire jumps out at you, carbon monoxide sneaks up on you. Too few small aircraft pilots carry adequate protection for either of these dangers.

Carbon Monoxide (CO)

You already know about carbon monoxide. CO is a gas that has no odor, taste, or color. Burning fuels generate CO. In an airplane, exhaust gases can sometimes get into the cockpit. But we seem to think it can’t happen to us.

One simple example is in our homes. When I was a home inspector, 50 percent of the time I would see log-burning stoves that were not vented. And although household CO detectors expire after five to seven years, 90 percent of the time I found detectors that were more than 15 years old, or no detectors at all.

Don’t be that complacent in your airplane. Install an active CO detector. Many pilots are still buying simple stick-on detectors. The unit’s orange center spot turns gray/black when carbon monoxide is present.

Instead of buying a few of these stick-ons for 10 bucks, I recommend you invest a hundred dollars or so in an active unit that will sound an alarm. You’re going to be too busy flying to be checking the little color spot every few minutes.

Fire Extinguisher

Don’t do what I did and grab any old thing from the house. I grabbed a Kidde dry chemical household type extinguisher to keep in the Pulsar. Fortunately, I never needed it. If I had, I would have discovered that the dry chemical agent can damage avionics, create corrosion, and be toxic inside a cockpit.

Get your extinguisher from any of the major aircraft supply houses. These are Halon and Halotron. Both are safe in a cockpit since they don’t leave residue, don’t corrode metal, and don’t damage electronics or instruments. And they don’t displace oxygen or create a dust cloud.

Sporty’s has a handy comparison guide for buying a fire extinguisher that you can find via the link at EAA.org/Extras.

Materials

You should have cushioning for sharp edges in the cockpit, especially the top rim of the panel area. When you’re in the cockpit making airplane noises, lean forward to see what you’re going to contact if your seat belt lets loose. All of these areas should be covered in some kind of padding.

You might be thinking that all of these details are going to cost you some money and time. Yes, they will. However, compared to the overall airplane, these costs are small. The extra details will go a long way in keeping you safe, confident, and in the air.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911, is a manufacturing engineer, A&P mechanic, EAA technical counselor and flight advisor, and former designated airworthiness representative. She built and flew a Pulsar XP and Kolb Mark III, and is researching her next homebuilt project. Lisa’s third book, Dream Take Flight, details her Pulsar flying adventures and life lessons. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com and learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com.