By: Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the June 2024 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

It’s that perfect spring day when you look around the airport and see a limp windsock, blue air clarity for as far as you can see, no airport traffic, and your airplane beckoning to you from its spot in the hangar.

“Ben, let’s go flying this morning. It’s perfect.”

“I thought I was going to help you clean out the hangar today?”

“We can do that later. This is an opportunity.”

“Let’s go.”

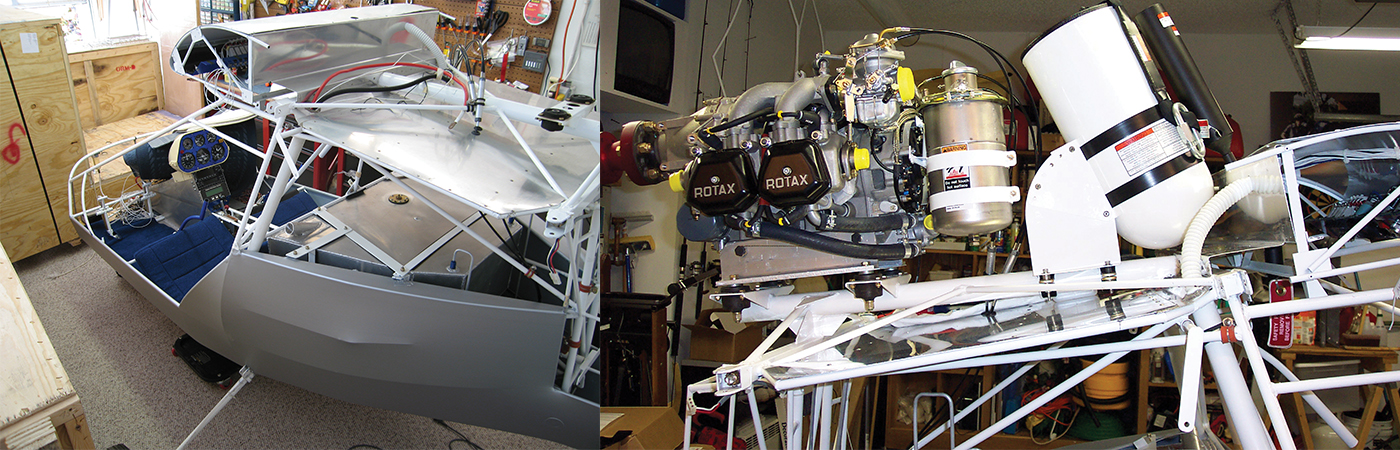

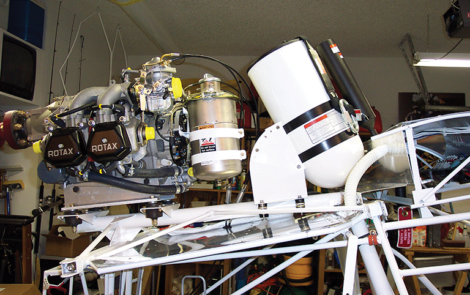

I pulled the Kolb out into the still cool morning sunshine. After the preflight, we jumped in and taxied out to the runup area. Taking off to the northeast, the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains loomed in front of us. I’d learned that even though winds were calm, the mountain air currents could be deceptive. In that moment of thought, an air bubble caught us and gave us a shake.

“Tighten your seat belt, Ben,” I said.

“I guess so. Where did that come from?”

“The gorge. I’ll climb a little.”

Soon we were over a small lake surrounded by jagged peaks. The sunlight reflected off the ice and snow left from winter, and glistened off the calm water of the lake.

“Stunning. I’d hate to think about a power-out or structural failure right here,” Ben said.

“Don’t even say that.” I said. “Look, we do have backup.”

I pointed to the red activation handle for a whole-aircraft parachute above our heads.

“Ah. Peace of mind,” Ben said.

Now in use for more than 20 years, many homebuilt kits offer the option to install a whole-aircraft parachute system, designed as a last resort in the event of an unrecoverable failure in the air.

It’s nothing new. Throughout the history of humanity, we’ve been tinkering with lowering large objects (besides ourselves) to the ground. In 1929, stunt pilot Roscoe Turner deployed a whole-aircraft parachute from his 2,800-pound Lockheed Air Express for fun in front of a crowd of 15,000 spectators in Santa Ana, California, landing uneventfully and walking safely away.

Should you install a whole-aircraft parachute in your homebuilt? While it may seem like a simple decision, it’s not. A variety of factors complicate the decision, not the least of which is cost. Here are the things to consider.

Why You Might Not Want a Whole-Aircraft Parachute

Deployments are rare. ASTM International reports that a 2017 National Transportation Safety Board study looked at 268 small aircraft accidents occurring between 2001 and 2016. Of the 211 instances in which the airplane did not have a parachute recovery system, 82 ended in fatalities. Of the 57 instances in which the airplane had such a system, eight fatalities resulted.

Although this certainly argues for the safety of parachutes, the sample size is small and the study is dated. According to the EAA database, more than 33,000 amateur-built/homebuilt aircraft are licensed by the FAA. This suggests that the deployments of whole-aircraft parachutes are low. Situations where their use is obviously helpful, such as structural failures or an unrecoverable spin, are rare. We’re taught to fly the aircraft all the way down and make the best of the situation, not pull an emergency handle at the first hint of trouble.

Cost. A whole-aircraft parachute will be an expense above and beyond the kit cost. The prices will vary depending on the weight and design of your airplane.

If you’re flying a typical ultralight, you may spend $3,000. Systems for two-place homebuilts will start at $6,000 to $8,000 and go up. A Cirrus Airframe Parachute System installed on an RV-10 will run you more than $25,000.

Extra accessories add weight. Installing a parachute will add 15 to 60 pounds or more to your project. Do the calculations and think about flying with reduced cargo space. Extra weight will also drive up your fuel costs and may change some of the aircraft’s flight characteristics.

Parachutes are less effective at lower altitudes. Many of the loss-of-control accidents we see in the vicinity of the airport are low-altitude accidents, especially the turn to final. A parachute needs space and time to deploy. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t pull the handle at low altitude; it just means the system may not have time to work properly.

Maintenance. You’ll want to add the parachute system to your preflight and condition inspection, and remove it periodically for repacking and rocket replacement at the factory. You only have to do this every five to 10 years, but it is likely to cost several thousand dollars at each interval.

Retrofits are difficult. If you are already flying your homebuilt and decide to add a parachute system, installing one may be expensive and involved. But don’t dismiss it if you’re willing to spend the time and money to do the proper design work for an installation. Begin by talking to the designer of the aircraft, who can answer the most critical engineering questions before you get deeply involved, only to realize it won’t work.

Since adding a parachute system changes the weight and balance of the aircraft, it’s considered a “major change,” so you will want to look at your current airworthiness certificate for further instructions. Talk to the FAA or your designated airworthiness representative. You will likely be put back into a testing phase.

If you are working on an original design, the system should be entered into the engineering calculations and flight characteristics and fully documented. You’ll also want a consultation with the parachute system manufacturer. You may need to design extra structure under the occupant seats and/or into the seats for cushioning and crushability.

If you’re simply adding the option that the kit manufacturer offered at the beginning, your work will be simple or difficult depending on the aircraft design. Tube and fabric will be easier than composites or aluminum. The manufacturer can advise you.

Pilot tricks. Some pilots may think that because they have a backup plan, they can take more chances with risky flying. Yes, this happens.

Parachute systems can fail. A system failure is rare but not out of the realm of possibility. Although highly unlikely, lines can tangle, the rocket may not fire, and the cable may malfunction.

The pilot decides not to use it. As an informed decision, this is fine. But sometimes pilots are afraid to pull the handle. If you have any doubts about surviving a serious malfunction, the parachute may save your life. Don’t hesitate.

Other troubles. Don’t assume that simply pulling the chute means you can sit back and relax while the airplane is being “gently” lowered to the ground. There’s nothing gentle about hitting the ground at almost 20 mph (1,700 fpm). The airplane can hit a tree awkwardly, piercing the cabin, the parachute can get tangled, or you could land in rough water.

Why You Might Consider a Whole Aircraft Parachute

After all that doom and gloom, are there good reasons why you should consider a parachute? Yes.

Peace of mind. After all the potential drawbacks, peace of mind may win you over. Any viable backup plan in an airplane is a good idea. As rare as it might be, at a sufficient altitude a parachute may save you from:

- A midair collision with another airplane or with a large drone or bird

- An engine failure in rugged territory

- A structural failure

- An unintentional or unrecoverable spin

- Jammed controls

- Pilot incapacitation or pilot disorientation

These are all rare events, but if you are in the middle of one, you or a passenger may be glad to pull the red handle. Don’t forget to include the parachute system deployment in the passenger safety briefing.

Peace of mind may be the single biggest thing that convinces you to go with the parachute system, overcoming the added cost and added time to install.

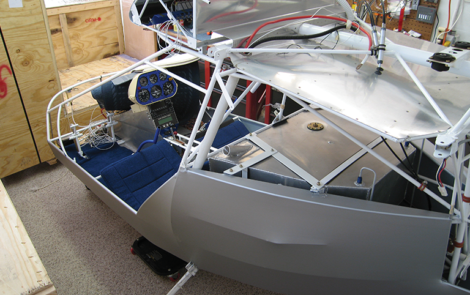

Designed for your aircraft. If you are building a kit, and especially a quick-build kit, a parachute system may be an option from the manufacturer. These are straightforward installations and are specifically engineered for your aircraft.

Ultralights. Ultralight aircraft are well suited for backup systems, and the systems are far less expensive than in larger two-place aircraft.

Insurance. A whole-aircraft parachute system may lower insurance premiums.

Resale. Future buyers will likely appreciate the extra safety systems you’ve installed.

If you do go with a parachute system, the advice from the manufacturers and from the training programs they provide is not to hesitate using it. Accident data show that more problems arose from the systems not being used than from deployment.

I decided to add the parachute to my Kolb simply for peace of mind. As a low-time pilot, I was risk averse and knew that I didn’t know what I didn’t know. I never used it, but I was glad it was there.

Deciding whether to purchase and install a parachute in your homebuilt is a personal decision with many things to consider. It has little to do with your flying ability; installing safety features and backup systems is smart. Some pilots who “pulled the red handle” have been ridiculed on social media, and this is a shame. Would we think switching over to a backup battery or alternator when we needed it a silly thing to do? Of course not. Anything we do to improve the safety and reliability of our airplane is smart.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911, is a manufacturing engineer, A&P mechanic, EAA technical counselor and flight advisor, and former designated airworthiness representative. She built and flew a Pulsar XP and Kolb Mark III, and is researching her next homebuilt project. Lisa’s third book, Dream Take Flight, details her Pulsar flying adventures and life lessons. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com and learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com.