By David Smith, EAA 1298935, and Ronald Smith

This piece originally ran in the August 2024 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

Following much reporting on the Hang Loose hang glider in various media through the fall of 1970 and into 1971, Jack Lambie came back to his home in California from a few months away to find three shopping bags full of mail waiting for him.

Jack, who had been in North Carolina flying a Wright brothers replica for a film, said, “Many had six- to eight-page letters, often from highly experienced pilots telling of their love of flight and how [the Hang Loose] seemed to be their long-sought dream. Some were from what were obviously 12-year-olds.”

My older brother Ronald was 12 years old when he wrote to Jack in early 1971. And this is the story of our Hang Loose flying machine, built in 1971 and still flying 53 years later.

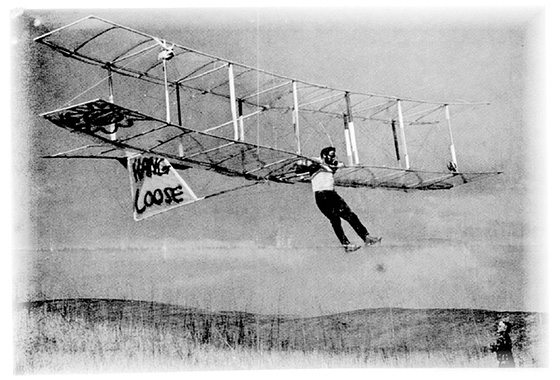

Jack, an unconventional soul, was a high school vice principal in the summer of 1970, teaching a summer aviation class to fifth and sixth graders. To make the learning experience more meaningful for his students, he decided to have them build a biplane hang glider in the final two weeks of the class. The Hang Loose was built by the students in their classroom. Once completed, it was taken out into the schoolyard where each student had two “flights” as fellow students pulled and pushed the machine across the schoolyard.

Shortly thereafter, Jack took the glider to some gentle grass hills near Mission Viejo, California, and it was there that the Hang Loose first truly flew. The photographs of that day’s flights are the ones that accompany Jack’s article “Downhill Racer” in the December 1970 issue of Soaring magazine. This was the article that inspired Ronald to want to build and fly a Hang Loose.

In early 1971, Ronald sent a letter to Jack requesting a set of Hang Loose plans. (Plans can still be found online via the link at EAA.org/Extras.) He included the required $300. Ronald was an avid model builder, and he surmised that this would be simply like building any other model — but admittedly much larger.

A month or so later, the “plans” arrived. These could not have been more appropriate for a now 13-year-old. Jack and his brother, Mark, illustrated the plans so that a 13-year-old could understand them, which gave the plans a comic-strip style.

In the spring of 1971, Ronald headed for the local lumberyard with Jack’s “wood parts” and “all the stuff you need” list in hand. Almost immediately, our father, a gifted aeronautical engineer and a keen sailplane pilot, could not resist joining Ronald in his endeavor.

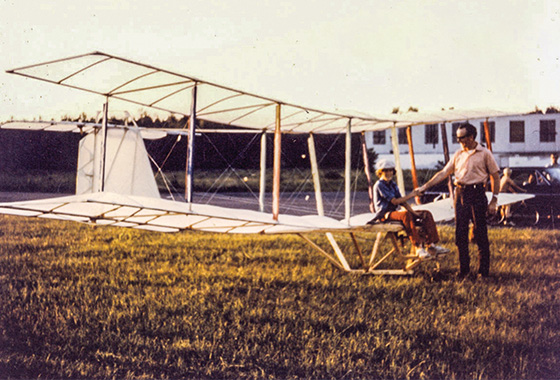

There was one minor detail that did concern our father. There were no usable hills anywhere close to the airport where we flew gliders. The solution was simple. We would add a seat, flight controls, landing gear and, operationally, we would tow the craft behind the family station wagon.

Our father grew up in the 1930s on a wheat farm in an era where farm equipment had to regularly be redesigned and substantially rebuilt in the midst of harvesting. This subsequently translated into an extraordinary ability to see engineering solutions to almost any problem he was confronted with.

At 6 years of age, I participated in the construction of the Hang Loose, which largely involved either spreading white wood glue or acting as a human clamp while various pieces were being assembled. Construction occurred in the basement of our suburban family home, and final assembly was made in a World War II building at Pendleton airport (CNF3), home of our gliding club, the Gatineau Gliding Club.

Two facts conspired to make the first flight of our Hang Loose quite spectacular. The initial position of the seat was such that the glider had a very aft center of gravity. To compensate, numerous bags of lead shot had been lashed to the front tip of the landing gear ski. Nylon ropes had been used to connect the control stick to the elevator.

When our father, acting as the intrepid test pilot, gave the launch signal for the maiden flight, the driver of the impressively large and powerful convertible sped away — and kept accelerating! In a moment, the Hang Loose was well past its VNE (never exceed speed). The combination of aft CG and lack of elevator control due to the elevator nylon ropes having stretched made the Hang Loose climb wildly. At some 30 to 40 feet of altitude, with a 20-25 degree nose-up attitude, our father released.

The Hang Loose came to a standstill, paused momentarily, and then descended in roughly that attitude until it impacted the ground. Surprisingly, little structural damage occurred. Within a week or so, everything was repaired. The seat was relocated forward of the wing, which gave our glider a correct center of gravity.

In the early fall of 1971, Ronald soloed in our Hang Loose at the age of 13. He had been instructed by my father who would sit on the tailgate of our family station wagon shouting helpful comments as the Hang Loose was being towed. That summer, and subsequent summers, I also actively flew Hang Loose, sitting in my brother’s or father’s lap.

By the summer of 1974, following a number of low-speed ground slides, I had enough experience to solo at the age of 9, sitting on top of two or three bags of 20-pound lead shot to ensure that the CG was correct.

After the initial flight testing, we decided that our Hang Loose should never leave the tether of the rope that attaches it to the car. Although initial flights were up and down a single grass runway, we rapidly learned to take advantage of our airfield’s three triangular runways (each 2,600 feet long). We are able to fly Hang Loose continually around the airport by rounding off the ends of the runways. Each flight took about five minutes to complete a full “circuit” around Pendleton airport. This airfield was built in 1943 as a World War II Commonwealth Elementary Flight Training School where students were taught to fly on a fleet of de Havilland Tiger Moth biplanes.

When Ronald or I are briefing a first-time Hang Loose pilot, we advise them that the elevator is quite effective, the ailerons much less so, but that they can be supplemented by yaw-induced roll via the rudder. Takeoff occurs rapidly, and the glider is typically flown at 5 feet of altitude. The glider generally stays behind the tow car except during turns when it is flown to the outside of the turn radius of the car. This allows the car to slow down slightly in the turn, in a similar fashion to a water-skier following a boat that is turning.

A few points are important to note when flying a machine with low wing loading. Our Hang Loose becomes extremely difficult to handle as soon as the wind is greater than 5 mph and slightly gusty. I believe that this is true of many of the early aircraft. We therefore tend to restrict operation to still mornings or evenings.

A critical piece of equipment that has helped us avoid damage over the years is the addition of a simple Hall Brothers airspeed indicator. This indicator is installed in front of the person driving the car. In the past, we had several incidents while turning from one runway to another, where we went from a light headwind to a tailwind.

It is difficult for the person driving the car to perceive the loss of a few mph of airspeed. This often resulted in the glider running out of lift and touching down on the pavement. Sometimes this was merely a touch-and-go, and other times it was a more serious “back to the barn for some repairs” occurrence.

Ronald and I are often asked what it is like to fly our machine. In some ways it is simple, and other ways it is somewhat surreal and profound. After 50-plus years of flying Hang Loose, we both still enjoy flying it and sharing the experience with fellow pilots. Of the hundreds of pilots who have flown the Hang Loose over the years, be they neophytes or highly experienced pilots, the end results are always the same — enormous smiles and a sense of wonder and amazement.

Sitting 5 feet in the air, at 22 mph, overflying wildflowers, smelling the fresh-cut grass of the grass runways, the odd grasshopper hitching a ride on the wings, reminds us of why two other brothers worked so diligently together to achieve flight in 1903.

David Smith, EAA 1298935, is a consultant overseeing the completion and deliveries of business jets. He is an active sailplane and power pilot and has flown throughout North America, including the Arctic and the Caribbean.

Ronald Smith has flown more than 125 aircraft types ranging from ultralights and homebuilts to an experimental Boeing 707 and wide-body Airbus A310s. Currently, his favorite mounts are an open-class sailplane and an Unlimited aerobatic monoplane.