Story and photos by Carol Smith Ferlo

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025

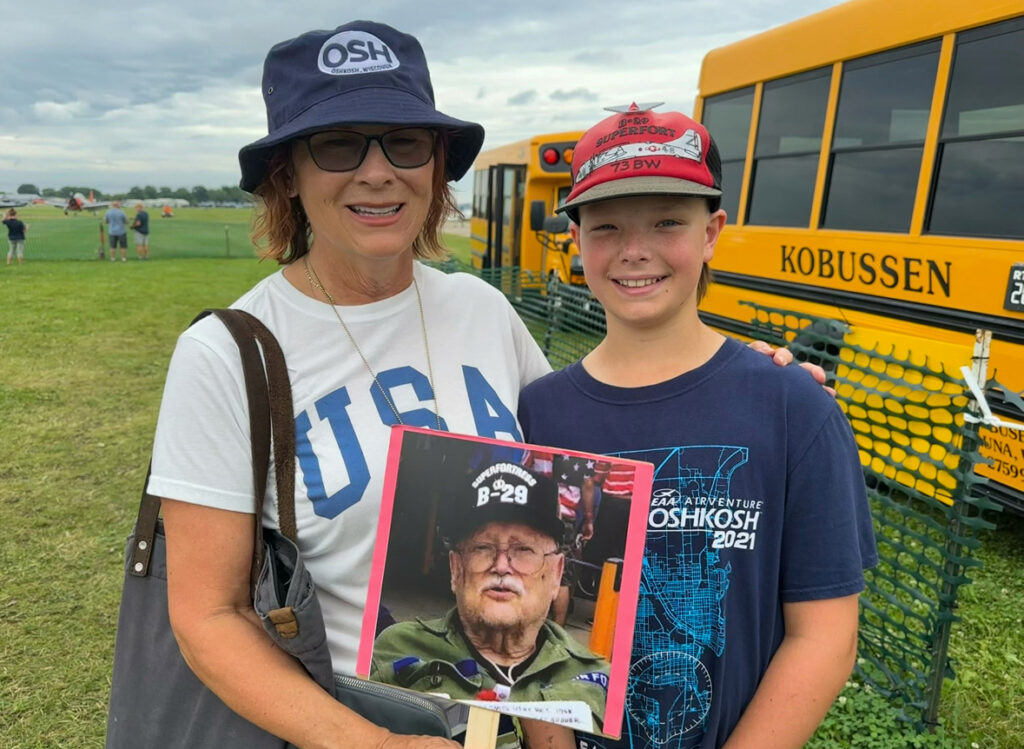

10-year-old Beckett Dovichi’s glee was uncontainable as he leaned his head toward the openwindow in the rear compartment of B-29 Doc. It was July 24, 2025, and we were in the midst of our Doc flight experience, flying a bit more than 200 mph at an altitude of about 1,500 feet. Once we reached altitude, our seatbelts and headsets came off, and we were free to roam from our assigned seats in the gunner section to the rear of the airplane. I imagined his great-grandfather’s (my dad) first time flying on a B-29. I can picture his youthful, good-looking face having a similar reaction as all the components of the flight became a part of himself, especially the distinct and deafening sound of those four engines during takeoff, and the whirring of the propellers. There was no noise-reduction technology in the 1940s. We were also hearing Doc, unfiltered. I can’t help but also imagine how terrifying these same engines must have sounded to those people in the targeted cities.

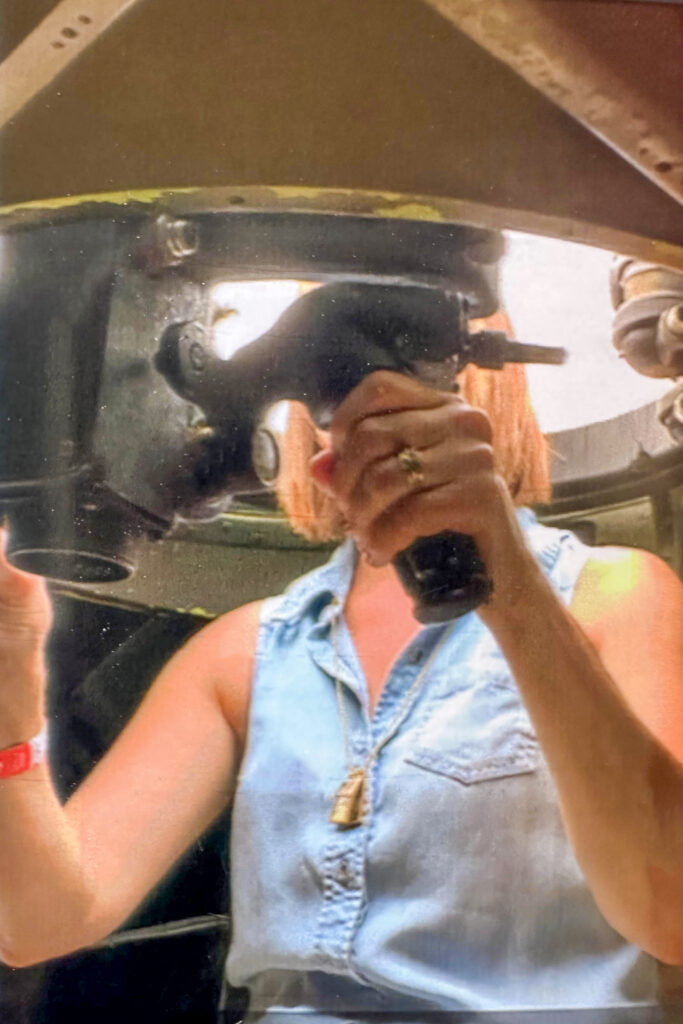

As I was writing this, I got a call from Beckett, and I asked him what stood out the most for him from his Doc flight experience. He replied, “Well, the whole flight but especially that open window and sitting up in the CFC bubble seat,” where his great-grandfather also sat. He also mentioned how noticeably loud it was when we took off the headsets. We were wearing them at the beginning of the flight, so we could hear the B-29 crew communicate with each other. That was very interesting, but it also muffled the sounds. In hindsight I wish we had not worn them during takeoff so we could have heard, fully, what it was like.

Our B-29 crew was outstanding in every way! They were warm, welcoming, informative, and took time with Beckett to make sure he got the most out of his experience. After we returned to the Appleton airport we were allowed to roam the whole airplane. Beckett loved sitting up in the nose and examining all those controls.

We even reunited with an old friend, Chris Henry! As the EAA museum manager, he volunteered to assist my dad when we made our visit in 2015. He also was very helpful to us on this visit.

My greatest hope in being a part of this experience is to keep the history of my dad, and the rest of the Greatest Generation, alive in the minds and hearts of all their descendants. I wanted it to be real to my grandson, and I believe how we experienced it is about as real as it can be. The following is a recap of our adventure 10 years ago.

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2015

The wheels on my dad’s walker grinded to a halt; his stooped form brought to attention as he took in the view before him. It has been more than 50 years since my dad last saw a B-29. While he liked the idea of this huge air show, he didn’t like dealing with crowds or having to “wait” for anything.

Patience never was one of his virtues.

He did, however, really love the EAA Aviation Museum, and over the years brought many visiting family members and friends to Oshkosh. West Bend, Wisconsin, was his home since the ‘60s.

Dad was now 91, and I had convinced him to attend the air show with me that year. Dad knew that the restored B-29 FIFI would be there.

Before I continue, the following is information and details of my dad’s life that I believe he would want you to know. Some of it is a little “techy” so please bear with.

The B-29 was “his plane” during World War II. At this time, FIFI was the sole flying B-29 from the almost 4,000 that were manufactured. About 450 were shot down or lost in combat, and the remainder were scrapped for metal and parts. What made this airplane challenging to fly was its four massive engines (Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone) resulting in more than 20,000 hp of energy. Early on in their use, B-29s were notorious for overheating, and many were lost in training operations while the “bugs” were being worked out. Sadly, my father lost a buddy in this manner, a few days after the war had actually ended.

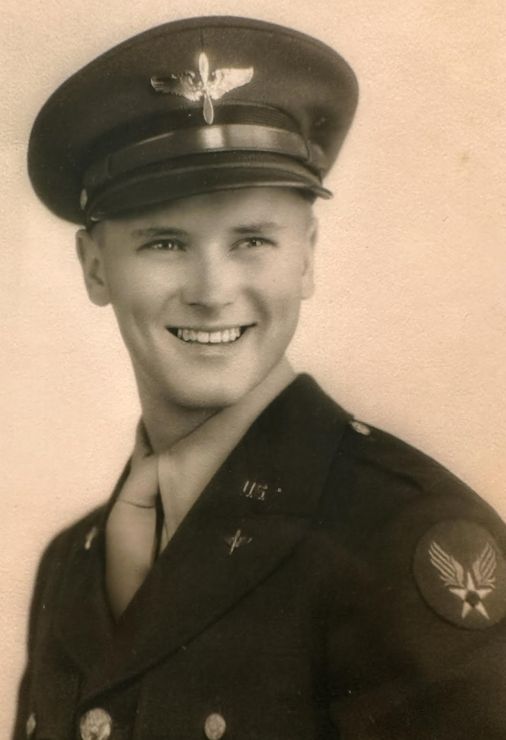

What made this bomber unique was that it had two pressurized cabins, connected by a long tunnel which contained the bomb bays. The General Electric Central Fire Control system on the B-29 directed four remotely controlled turrets armed with two .50 Browning M2 machine guns each. All weapons were aimed optically, with targeting computed by analog electrical instrumentation. There were five interconnected sighting stations located in the nose and tail positions and three Plexiglas blisters in the central fuselage. Five GE analog computers (one dedicated to each sight) increased the weapons’ accuracy by compensating for factors such as airspeed, lead, gravity, temperature, and humidity. The computers also allowed a single gunner to operate two or more turrets (including tail guns) simultaneously. The gunner in the upper position acted as fire control officer, also known as central fire control gunner, managing the distribution of turrets among the other gunners during combat. This position was assigned to my father, Sergeant Gunner Ralph E. Smith.

Pilots and their bomb crews formed very strong attachments with “their” airplanes. During the first several years of the war, crews would often hire one of their own artists to paint a design of their choosing onto the nose portion of their bomber. There was a variety of catchy slogans, accompanied by a figure — sometimes cartoonish, sometimes a scantily clad “bombshell.” A couple of examples are Ponderous Peg, Shady Lady, and Devil’s Darlin. You get the idea. There were also some fun cartoon styles like Doc, which has since been fully restored and is now flying along with FIFI. In April 1945 an order came down to have all nose art involving women removed from the airplanes. My dad, with a trace of disappointment in his voice, attributed this change to “some general’s wife.”

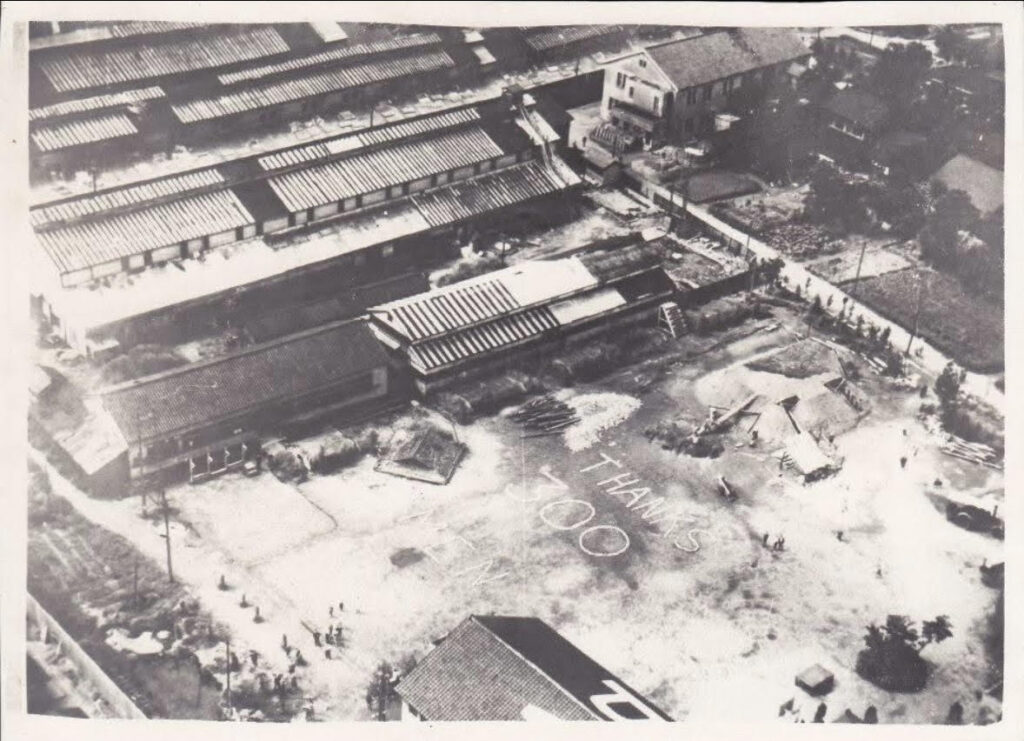

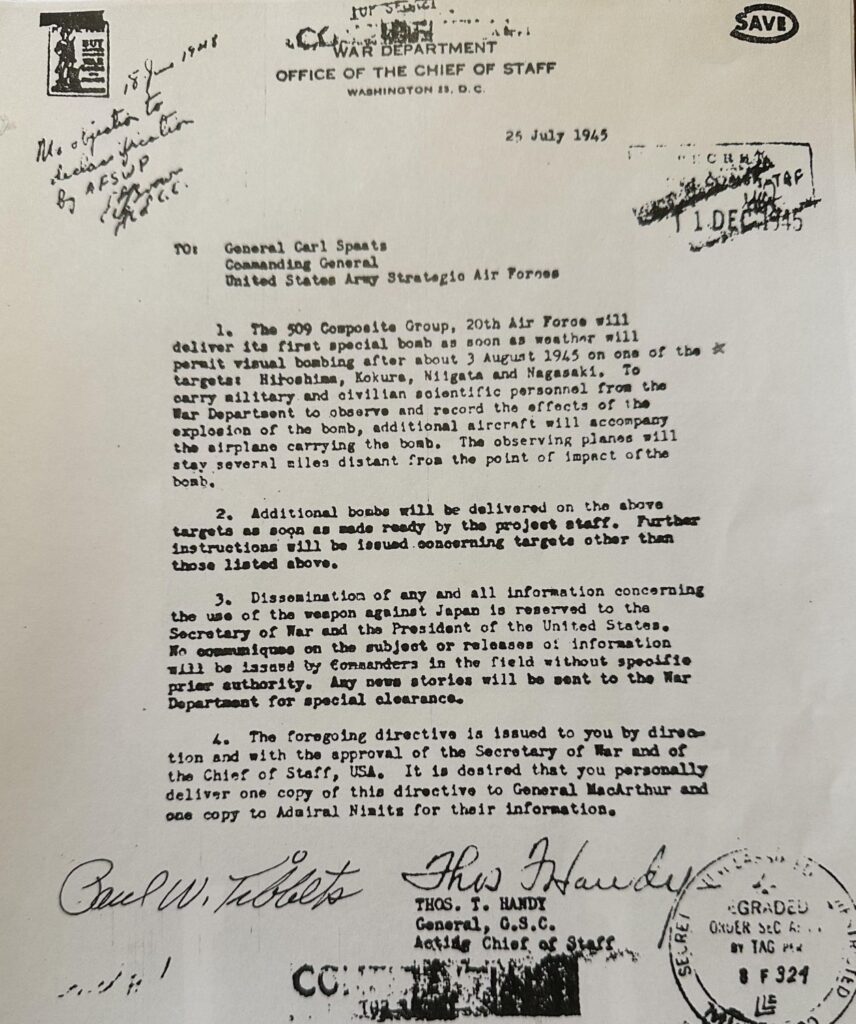

In wartime, the B-29 was capable of flight at altitudes up to 31,850 feet and speeds of up to 350 mph. This was its best defense because Japanese fighters could barely reach that altitude, and few could catch the B-29 even if they did attain that altitude. In summer of 1945 the decision was made to have the B-29 drop two atomic bombs over targeted cities on Japan’s mainland. At that time Japan, though hopelessly losing the war, did not believe in surrender and was preparing for a massive invasion by the United States and its allies. They were arming their citizens (by this time, mostly the elderly, women, and children) and training them to defend at all costs. This would have amounted to an enormous loss of life for not only the Japanese citizens, but for all of the army, air, and naval forces as well. As horrible as this decision seemed, it was the only solution for a quick ending to this prolonged conflict. The B-29 Enola Gay flown by Col. Paul Tibbets (whose signature is on the order), dropped the first bomb called Little Boy on Hiroshima on August 6,1945. Bockscar, flown by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, dropped the second bomb called Fat Man on Nagasaki three days later. Conventional bombing raids on Japanese cities continued even after the atomic bombings, increasing the ongoing pressure on Japan to surrender. On September 2, 1945, the Japanese Empire surrendered, ending the war. After the Japanese surrender, the next order was to strip the airplanes down to bare bones and send every available airplane to Japan to pick up our prisoners of war. These men were living skeletons and were the top priority. Nobody was going anywhere until those men were out and on their way home. The number of deaths among POWs held by the Japanese was notably higher than in POW camps run by Germany or Italy. Of the roughly 28,000 American POWs held by Japan, more than 11,000 died in captivity, with more dying after rescuing due to the extreme physical and mental conditions they were battling.

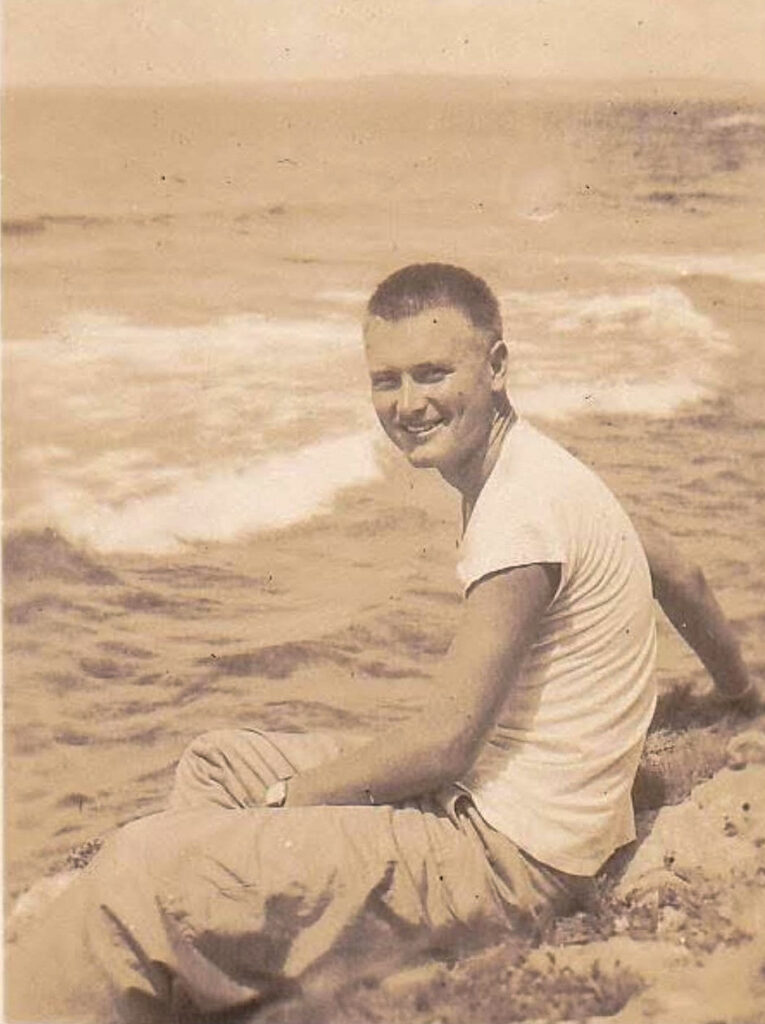

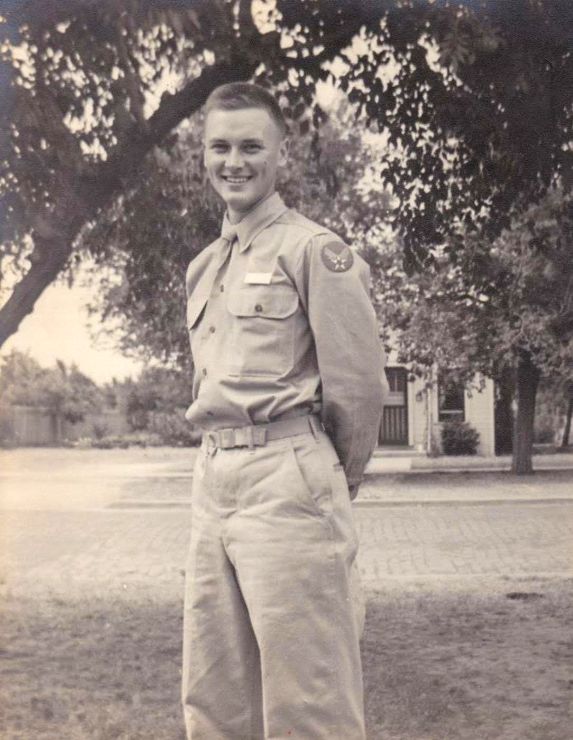

Ralph Edward Smith was born on December 1, 1923, and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He had wonderful parents who cherished and doted on their only child. Ralph admits that he was somewhat of a mischief maker. He confesses that he was an obstinate and sassy kid, “if someone said something was white, I swore it was black.” He had a lot of time on his hands and was adventurous, as well as inventive, which led him and his neighborhood buddies into various scrapes. Most were harmless fun, but one sad experience occurred when they set up a zip line in their nearby woods, which came apart with one of his buddies taking a fall and hitting his head, resulting in a head injury from which he did not recover. Generally, Ralph’s childhood was happy, and he wanted for little. He was also a good-looking kid and did some modelling for a local publication.

After graduating from Washington High School in 1942 he enrolled at Milwaukee State Teachers College (now UW Milwaukee). WWII was well under way with the U.S. having entered the conflict the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and there was no end in sight. The day came (1943) when Ralph received his “invitation” to serve his country. He took this invite, along with his “excuse slip” (apparently, he had a pre-approved pass to defer his enlistment until after graduation from college) to the dean’s office and reminded him that he was to be omitted from this conflict until after his graduation. The dean asked to see his papers then proceeded to tear them into pieces, and …. into the trash can. Ralph chose to become an official member of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF). His parents came around to the fact that their son was now a part of this huge conflict. They wrote to Ralph every single day that he was enlisted and sent care packages on a regular basis. Ralph regretted not saving any of those letters. His parents certainly would have saved their letters from him, but they seem to have disappeared, along with the years.

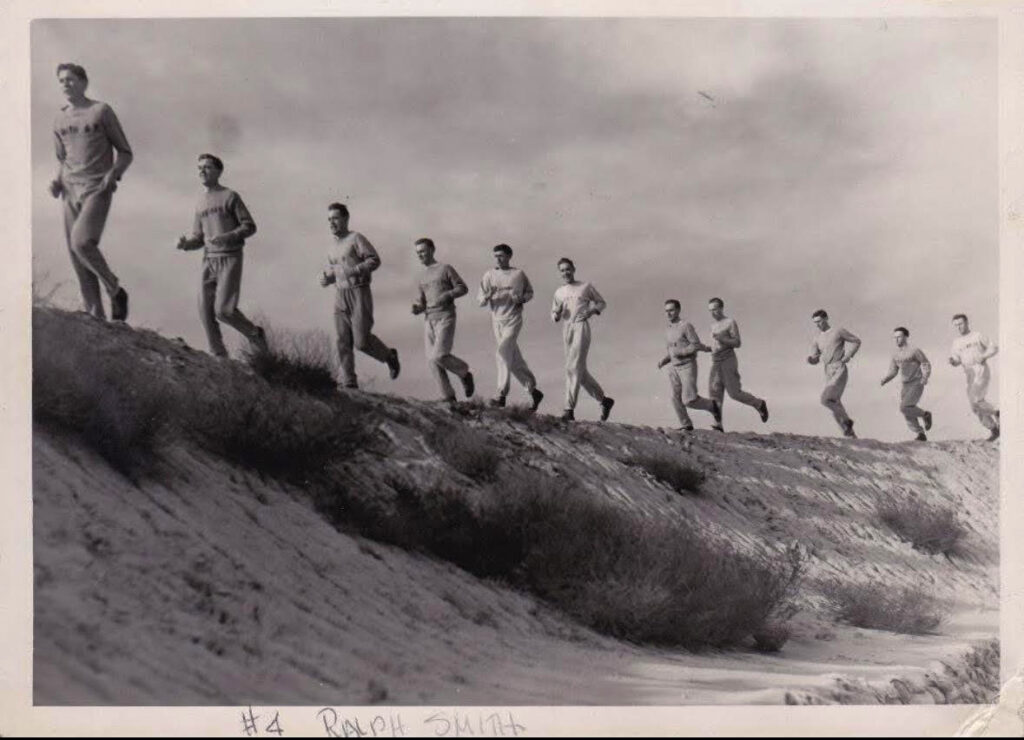

Ralph really wanted to become a fighter pilot, but the need had decreased by this time as the allies were winning the fight in the sky. He started his basic pilot training in Wichita Falls, Texas. From there he trained at Canyon, Texas. While in Texas Ralph found himself in serious trouble. While out on the town with some buddies, and stoked with “liquid courage,” he mouthed-off to a Marine sitting at a nearby table. This Marine was half a foot taller than Ralph and outweighed him by at least 50 pounds, and he was a Marine! This guy got up and was on his way over to take care of this mouthy army/air brat, but his own buddies talked him down when they saw how small Ralph was in comparison. Ralph’s buddies filled him in the next day as Ralph had absolutely no memory of the event. Along with consuming alcohol, Ralph also smoked throughout his active years in the military, eventually quitting both after he met his future wife, Miriam.

Ralph attended ground school for pilots at Santa Ana, California, where he studied math, navigation, and code for pilots. Next it was on to Tulare, California, for flying school where he flew open-cockpit biplanes. His basic flight training was at Taft, California, where he flew BT-13s, which were aluminum single-wing airplanes with closed cockpits and fixed landing gear. He took his first solo flight there from Taft to Sacramento and back. At Luke Field in Phoenix, Arizona, he attended advanced pilot school where he “washed out.” Ralph would want you to know that while he technically washed out of flight training school, it wasn’t because he wasn’t qualified. His instructor made a point of telling him that due to the success of the war effort at that time, he was ordered to cut his trainees by 75 percent. Part of that decision was based on height and weight. Ralph was only about 5 feet 7 inches and had a slight build. Though he was deeply disappointed to not be allowed to continue his dream, it made him feel better about the reason why. Knowing about Ralph’s disappointment, his instructor told him about a newer bomber, the B-29 Superfortress, that he thought Ralph would find interesting. He was indeed very excited to become a part of the B-29 gunner crew.

At Lowry Field, Colorado, he trained to be a B-29 gunner, then at Fort Myers, Florida, he trained in aerial gunnery. He had to shoot at a banner being trailed in the sky by an airplane. Each gunner had bullets with different colored paint so they could tell who was able to hit the target. The gunners were told that there would be “hell to pay” if they hit and disconnected the towrope.

Christmas 1944, Ralph went to Lincoln Air Base in Omaha, Nebraska, to become part of a crew and from there the crew went to Alamogordo, New Mexico, where they trained together on B-29 bombers. Once during training, they had engine trouble while over California and had to land there. They were flown back to their base in an airplane belonging to a general and learned what officer luxury was when they sat in seats with padded cushions. While in New Mexico, they made a trip to Mexico and purchased leather shoes — which subsequently turned green and molded in the South Pacific.

Before heading into the conflict, Ralph did get occasional leave and there would be much excitement, anticipation, and preparation back home in Milwaukee. On one occasion Ralph flew into Chicago for the first leg of his journey home and remembered that a buddy of his was playing the organ somewhere in the city, so he looked him up and visited for a while. He then boarded the train for Milwaukee and “happened upon” the Eagles Club where a ball was taking place. He spent a good deal of time there — dancing, visiting, and having a drink or two. After some hours he made his way home to N47th Street, where he found his extremely worried (and now, agitated) parents, along with about 50 guests. Unknown to Ralph, his parents had planned a surprise welcome for him. When he didn’t show up at the expected hour they grew frantic with worry, calling hospitals, police, and any friends or neighbors that were not at the party! He didn’t intentionally mean to be unreliable, but he said that he had grown up being the center of attention and had gotten used to life revolving around himself. Another leave involved Ralph flying home for a funeral. As he was preparing for his flight back his thoughtful mother gave him a box of chocolates to give to the Red Cross workers as a thank-you. Those chocolates never made it to the intended recipients!

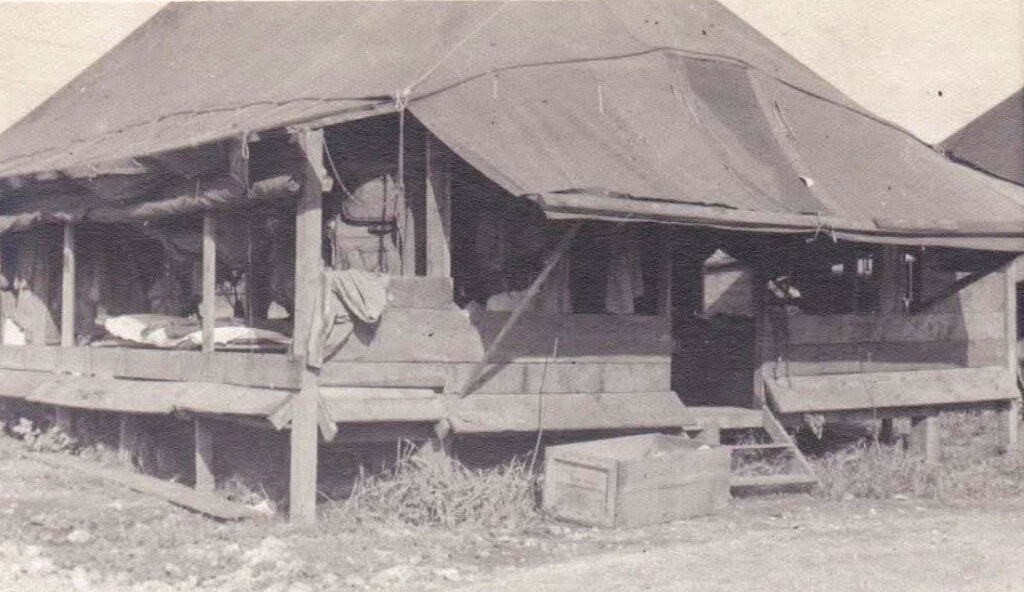

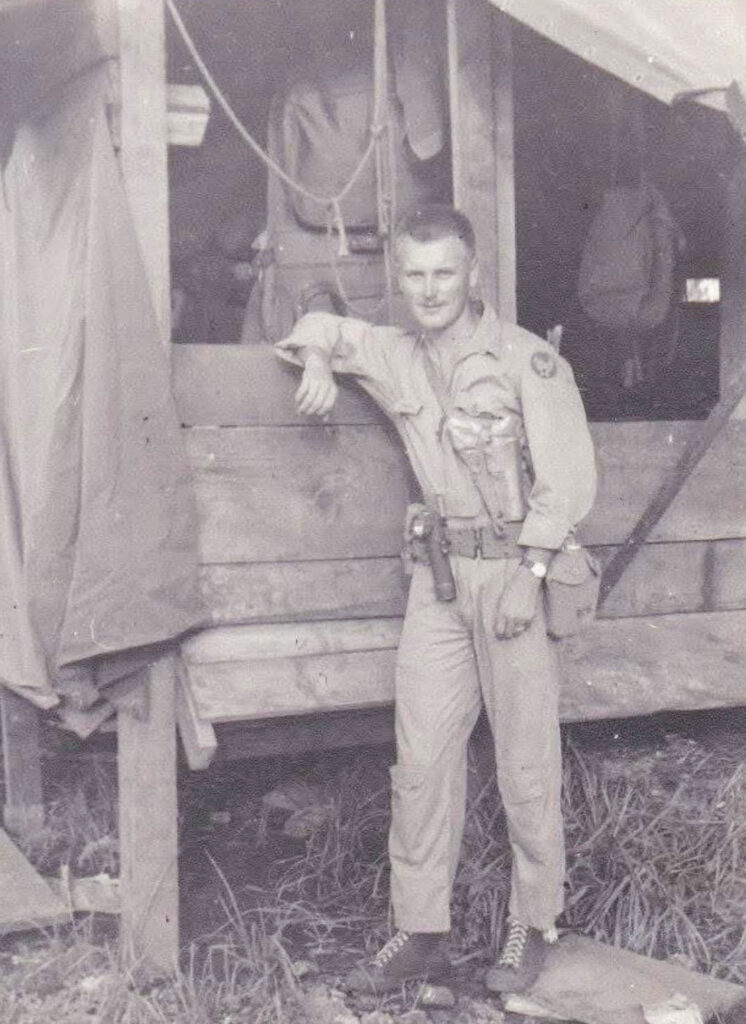

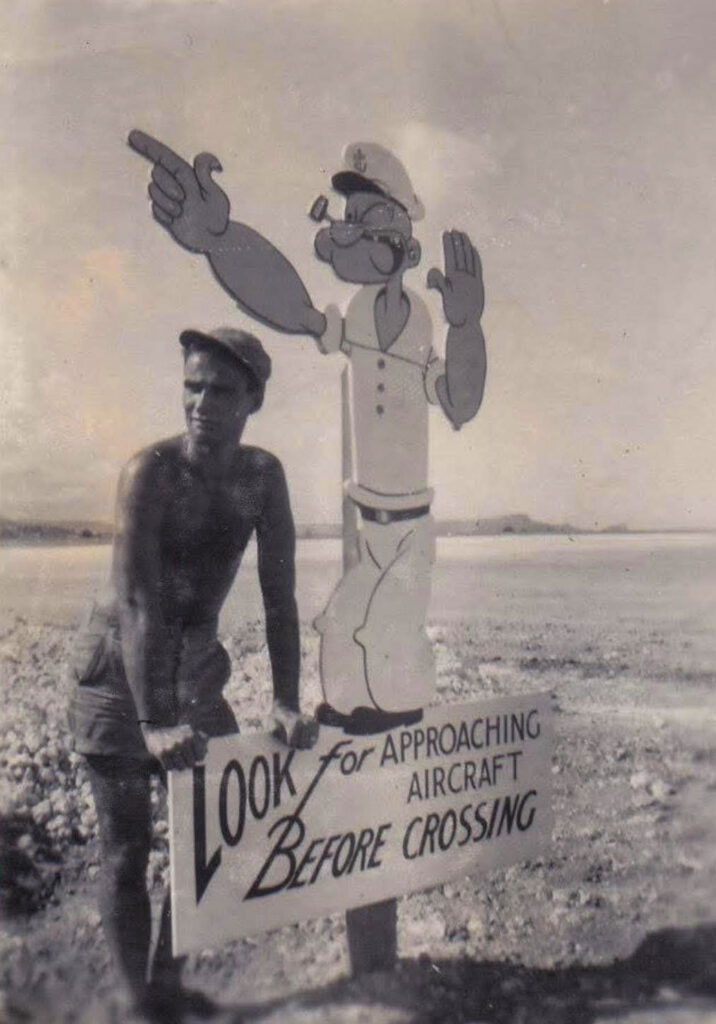

Ralph thought he would be sent to China, so he purchased a map and assigned numbers to the various provinces so that he could write to his parents and tell them “in code” where he was. However, he was instead sent to the Japanese island of Saipan. He and his crew thought the brand-new B-29 they flew to Saipan was going to be their airplane, so they polished it up and gave it the greatest care. They were disappointed when it was replaced with a much-used bomber. In Saipan the bomb squadron lived in a 10-man tent, raised two feet above the ground because of flooding. The men showered using salty sea water. The area was sprayed with DDT to kill mosquitoes, but their tent swarmed with chameleons.

As earlier stated, Ralph was the CFC for his bomber. He spent the remainder of the war on the B-29 in the Pacific, on the island of Saipan. First it should be noted that following intensive naval gunfire and carrier-based aircraft bombing, on June 15, 1944, the U.S. Marines landed on Saipan. For 24 days the Marines met a fierce enemy, and advances were slow as many of the Japanese were hidden in caves and strongly resisted the Americans. Estimates indicate that close to 3,500 Marines and Army personnel were reported as missing or killed. This invasion paved the way for the building of bases and runways for the coming B-29 bombers. Saipan was the first of the Japanese islands to be invaded. “Our war was lost with the loss of Saipan,” one of Emperor Hirohito’s admirals observed. Sadly, after the occupation, the Japanese civilians remaining on Saipan were instructed, by propaganda broadcasts from Tokyo, to take their own lives rather than suffer the humiliation of American occupation. Thousands of Japanese men, women, and children gathered on the northern tip of Saipan near Marpi Point (others at Banzai Cliff) and threw themselves from the towering heights. Desperate pleas to stop, broadcasted by their own soldiers who had surrendered, did not stop the madness. Marines and GIs found hundreds of bodies below! It’s hard to imagine the effect that this sight must have produced, along with the other horrors already experienced by our Marines and GIs. Just weeks after the Marines later invaded Iwo Jima, Ralph had a short layover on the island and he made a point of thanking the Marines still there for their hard-won battles, at both Saipan and Iwo Jima — quite a different encounter with the Marines this time.

On August 1-2,1945, Ralph’s B-29 (48 Z) flew in the very last conventional bombing mission of the war, the Japanese city of Toyama. It was a night mission, and because of prevailing, strong, and changing winds, all their bombs had to be released at 10,000 feet rather than the usual 30,000 feet or they would be blown off target. On their first pass over the city the bomb doors refused to release, so they had to circle around again while the crew repaired the doors. When the bombs fell, the squadron’s combined efforts destroyed 96 percent of the city. Years later, Ralph learned from a magazine article that there was an American POW camp based in Toyama, and this camp was the only part of the city that was not destroyed. No Americans were even injured!

Ralph was lucky enough to come home on one of the last “sunset” flights in a B-29. Some of his companions were sent home by ship and took months to get home. He eventually ended up on the island of Tinian (which was the launchpad for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) living in a Quonset hut. Tinian had housed what was then the world’s largest airbase, with hundreds of B-29 bombers. His first assignment after the war was working airport security. He and a buddy had to drive a jeep around the perimeter. Ralph considered this “make work” because there was nothing else for them to do. Ralph did not have a driver’s license; he had never driven any vehicle! He was the assigned driver because he was the ranking NCO. He taught himself how to drive and to manage the clutch.

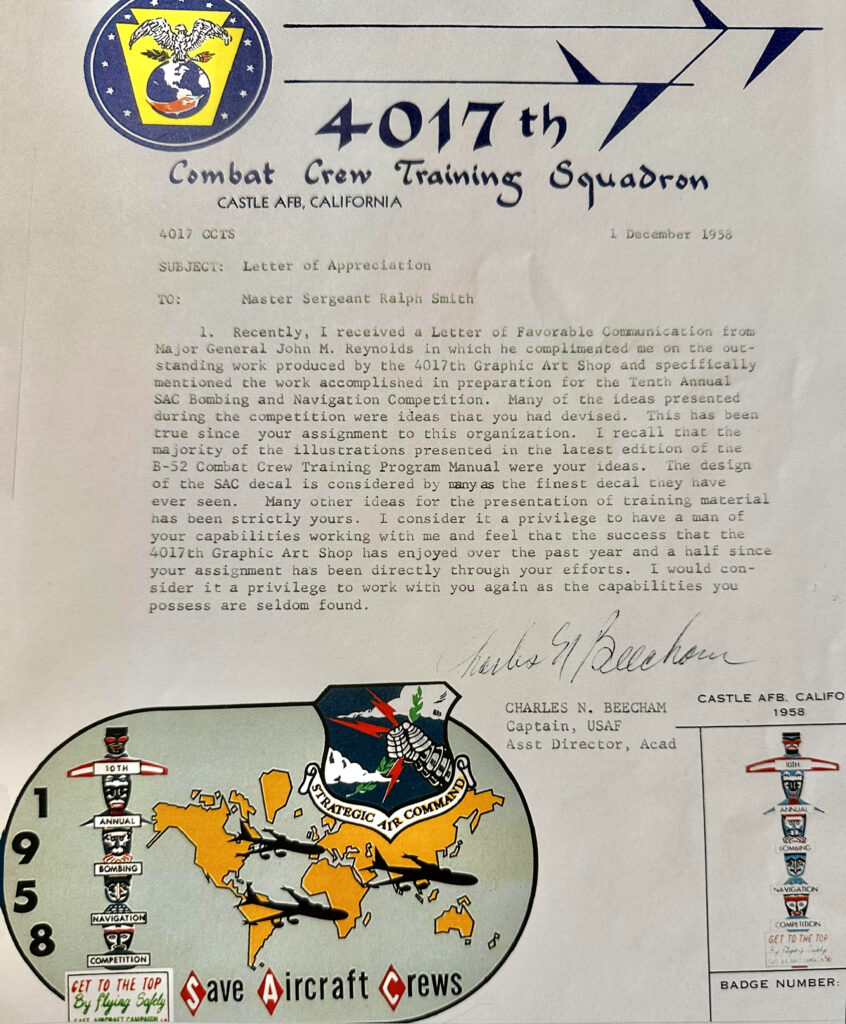

Ralph has often said that being a part of this conflict was his greatest life accomplishment. As an only child he really enjoyed the teamwork and general camaraderie of his gunner crew and stayed in touch with each of them, eventually outliving them all. He reenlisted, staying in the military until retirement. During the Korean War he was stationed at March Air Force base in Riverside, California. In the late 1950s he was stationed at Castle AFB, California, and was selected to work in the graphic arts department. Ralph was assigned to design a new decal for the Air Force which earned him a letter of special recognition.

The details of Ralph’s active service are 20th Air Force, 73rd Bomb Wing (CFC), 500th Bomb Group (B-29s), 883rd Bomb Squadron (each having 15 bombers), Bomber 48 Z.

Back to AirVenture 2015

For weeks I had been in contact with a volunteer from EAA regarding our visit — transportation around the grounds for my dad, and him seeing the B-29 FIFI, which was the sole purpose of our visit. I had explained about my dad’s service in WWII and his age factor. Everything was all set and ready to go. We arrived at the EAA grounds early and were picked up by a golf cart, speeding off to the area where the bombers were displayed. As we looked around, it became apparent that FIFI was nowhere in sight. The volunteer made a phone call and then informed us that FIFI was not here after all but was based at the Appleton airport on this day because it was giving flights from there. We took a few minutes to process this turn of events and decided that we would now make the drive to Appleton. As we were talking this over, my dad turned away, seemingly distracted, and cocked his head to the sky. A little dark spot grew larger, coming ever closer, and now, louder. It was FIFI! My dad recognized the distinctive sound of those B-29 engines and heard it long before the volunteer and I did. FIFI circled the field and landed, pulling up to her designated spot. We made our way over to the bomber. Dad picked up his pace (even with using the walker) but stopped a short distance away from the airplane, just taking it in.

I really wonder what thoughts and memories were going through his mind. As he edged closer, the crowd parted as they became aware of my dad with his green military jacket and cap, bearing insignia of his service and of his B-29.

We probably stayed for about an hour as the pilots and crew had questions for him. Everyone else just pulled up to listen. Dad, naturally, was in his element! He may have been 91 years old, but he had a razor-sharp memory and could recall details like it was yesterday! He also handed out copies (he just happened to have along) of the order for the atomic bombings. In the 1950s a lot of information and photos became declassified, and my dad (stationed at Castle Rock Air Base in California) scooped up a large quantity. People were very impressed with that document. It dawned on me that it was becoming rare to see a veteran from WWII. The pilot also welcomed me to climb up into the belly of that airplane. I sat in the pilot’s seat, in my dad’s seat (up in the bubble), and climbed through the tunnel to the rear cabin. I decided that someday I wanted to be a part of a B-29 flight. My dad was ready to head home after seeing FIFI, but I convinced him to stay for the air show. We settled in under some shade and enjoyed it to the end, especially the roar of the F-15s! We never did find out why FIFI (when it was giving rides out of Appleton) just happened show up when it did, but we sure were glad it did! I like to believe that a guardian angel was looking out for his charge.

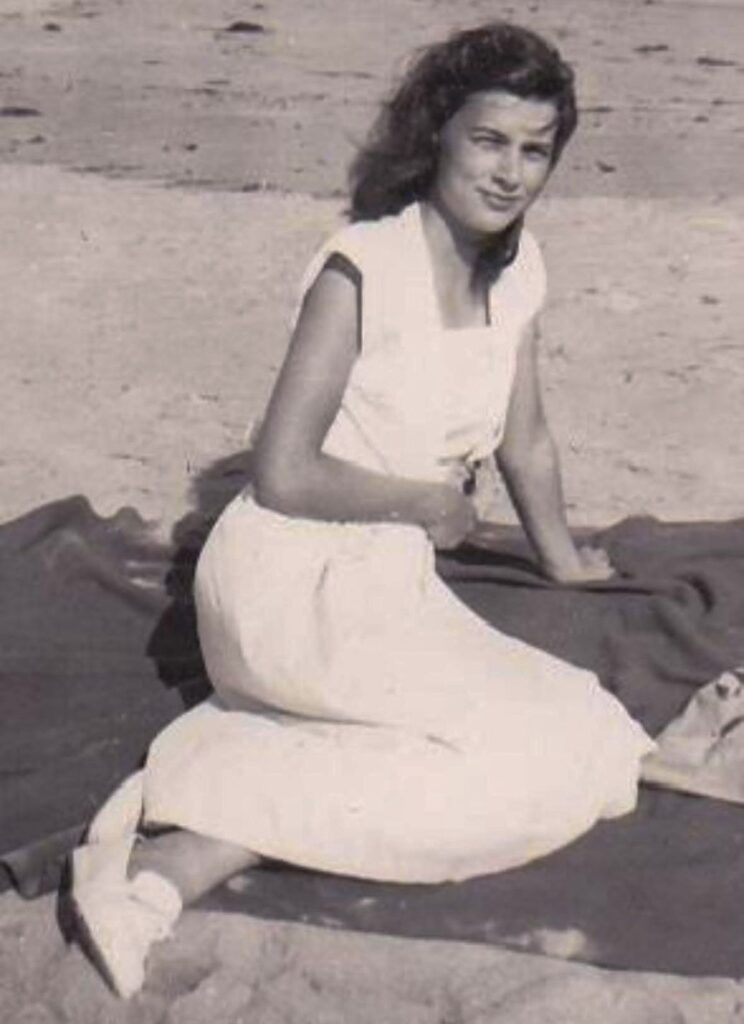

My dad did go on an Honor Flight with his granddaughter (my daughter), Lindsey. It was 2010, the year that a documentary was being made about the flight and they make a brief appearance in that film. We watched it at Miller Park in Milwaukee. Lindsey said that her grandpa showed his favorite photo of his wife, Miriam (Newport Beach, California, 1951) “all day to everyone!”

Several years ago, my daughter Lindsey and I booked a flight for the B-29 Doc during AirVenture.

A couple of nights before our flight I got an email that said Doc was temporarily grounded due to mechanical concerns at the last air show and would not be giving flights until further notice. We never did get that flight accomplished, but I am thinking that at EAA AirVenture 2025, the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII, would be a good year to do the flight.

A few months ago, my grandson (Lindsey’s son) Beckett (age 10) surprised me with a model he made of a B-29. It was perfect and an exact replica of a model we had as children when my dad was stationed in Japan. This year I plan to take Beckett on the B-29 Doc flight experience. We are beyond excited to be doing this together! There is a four-generation photo included that shows Beckett as a baby, holding onto his great-grandpa’s finger. This was taken shortly before AirVenture 2015.

I am so thankful that my dad and I took advantage of attending EAA AirVenture in 2015, as Dad passed in July 2016 (during the same time as AirVenture).

As his casket was being wheeled out of the church, an old, familiar favorite played out of the speakers, “Off We Go Into the Wild Blue Yonder.”