By Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911/Vintage 724296

This piece originally ran in Lisa’s Airworthy column in the July 2025 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

A strange thing happens to a new pilot. Along with the exhilaration and the enthusiasm come a strong desire to own an aircraft. As I wandered the air show, taking in all the sights and sounds, I saw a banner waving over a small two-place composite aircraft called a Pulsar. I was drawn to it. As I got closer, someone handed me a newsletter.

“Airframe kit only $17,995.”

I looked back up at the airplane. Could I afford to buy the kit? Emotions went wild as I realized I could actually afford to buy an airplane kit.

Or could I? At that point, it didn’t matter. I wanted that airplane.

By the time I left the air show in 1995, I’d put a deposit down on the Pulsar, not realizing what it was really going to require. I found out soon thereafter. Somehow, I got through all the surprises that followed and completed and flew my kit airplane. However, it doesn’t always turn out that well for those who enter the project clueless like I did.

I’d forgotten — or chose to forget — that a fuselage does not make a flying aircraft. A few other items, like an engine and avionics, will be important. And then you’ll need all the little parts that make everything work together.

Later, as a technical counselor, I felt slightly better as I realized other pilots were making the same mistakes I made. I decided to pull those lessons together for those of you who need to make choices about engines.

Engines are perhaps the most exciting part. They’re the heart of your aircraft. One of the biggest thrills is the day you tie your airplane’s tail to a post, tree, or truck and jump into the cockpit without the wings on and start the engine for the first time. It’s a milestone.

Here are the top traps to avoid when it comes time to choose your engine.

Not doing enough research. The engine and associated components may cost you as much, if not more than, your airframe. If your kit comes with only a few choices, then it will be straightforward. However, if you are assembling a Van’s kit, building a kit from plans, or working on your own experimental design, you have many choices.

If you’d rather not get into the nitty gritty of engine choices, you should consider building a kit that has specific recommended and matched engines. But, if you have many choices, then research is critical.

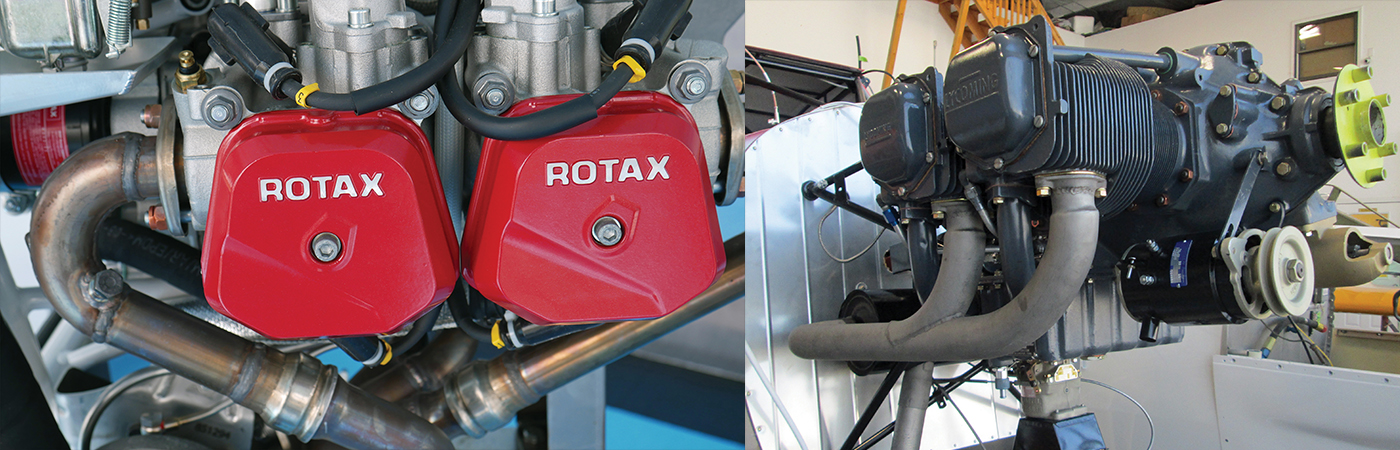

Rather than being a binary choice between a new engine and a used engine, we have options like buying a core and getting a rebuild, choosing a Lycoming or Continental clone, getting a used engine out of another experimental aircraft, finding an automotive conversion, or buying a Rotax or other alternate engine type.

Start with the EAA videos on engine choices and Homebuilders Week webinars. Study these topics before making any decisions. Then go to KITPLANES and the other data available for choosing your engine. An internet search will turn up a surprising amount of information, and you can find some links to help you get started at EAA.org/Extras. You’ll read and hear lots of advice and begin to develop some direction for yourself.

Some things you’ll learn include:

- How to match a particular engine to a particular airframe

- Weight versus horsepower

- Used versus new

- How to evaluate a core

- Rebuilds and overhauls

- Certified versus experimental

- Geared versus nongeared

- Cost, lead times, and more

If I were to take you through all these options, this article would be a book. The information is already out there, and you should plan to navigate all of it with an open mind. If you skip this important step, your chances of being unhappy with your engine choice go up exponentially and you’ll spend more money than you want to.

Accepting too much risk. Risk can come in many forms. Sometimes we don’t even realize we’re raising risk levels.

- Safety risk. Look at the accident records for our amateur-built aircraft. You’ll discover that aircraft with automobile engines have more troubles. This doesn’t mean that putting an auto conversion in your homebuilt is wrong or bad. However, it does mean that risk goes up if the match is not done well or the condition of the engine is not good.

- Mechanical reliability risk. If you’re a mechanic and comfortable around engines, this may be less of a problem. But if you’re not a mechanic and don’t care to become one, you should narrow your engine choices to the more reliable side.

- Ease of maintenance. How complicated is your engine choice? How much work will need to be done for your condition inspections and servicing? Will you do the inspections and maintenance? The answer to these questions will be different between an aircraft with a 160-hp Lycoming and an aircraft with an 80-hp Rotax.

Quitting the build because you ran out of money. This sounds avoidable, but it’s really easy to fall into this trap because it sneaks up on you. We have a habit of rationalizing our choices even when we know it might not work out.

When I bought the Pulsar fuselage, I knew I would purchase the rest of the kit. I was lucky that there were only a few choices on engines. There was only one recommended engine — the Rotax 912 — and the factory said it would arrange for the engine to be shipped to me when I asked for it.

Thorough planning, a budget, and timeline at the beginning of your build will help you at the end when you are excited about finishing. The last thing you want is to be overwhelmed and depressed. Your engine research at the beginning will also give you smart budget choices, including getting your engine from a rebuild shop.

If you find yourself in a bind near the end, stop and regroup rather than making hasty decisions about selling your project. Make sure you’ve explored all avenues to get in the air, including sharing ownership, joining a club, or arranging for a loan. Only you can know what you’ll be comfortable with financially.

Engine Choice Tips

Builders’ Group. Starting your research with this group will be a time shortcut and a confidence booster. The bigger this group is, the better it will be for you.

If there is no builders’ group, find anyone who has built or is building what you’re building. Even one voice to consult about engine choices will be helpful. The next step is to consult with the pilots who fly behind the engine you are considering. Even if it’s not the airplane you are building, the experience with the engine will be helpful.

Rebuild Shops. This is another place to do your research. Don’t go to an outfit that opened its doors two months ago. Find out what its specialty is and talk to customers. Ideally, you want a larger shop with all the tools and equipment for specialty work and a good track record.

Engine Prebuy. This goes without saying, but I’ve seen enough wild purchases by builders to know that the prebuy is not always on the required list. It should be. Get a thorough, independent checkout when buying a used or rebuilt engine for your airplane.

Has the engine sat for a long time? Engines that sit for an extended time are okay if they have been prepared for storage. If they have not, then corrosion may rule the engine out.

Comfort level. The less experienced and more uncomfortable you are with firewall forward, the more you should lean toward an aircraft kit with a few recommended engines. This makes it simpler, components will fit well, and instructions should be detailed.

Match your engine with the best propeller for it and the flying you are going to do. Talking about propellers is another book in the making. Get manufacturer and builders’ group advice.

Consider a kit engine. Don’t automatically rule out assembling a kit. Even if you feel you don’t know your way around an engine, a kit can be a great experience, especially if you attend a build school or team up with an A&P mechanic. Although you’re not likely to save money on a kit, you will learn about engines and have a great time.

Don’t avoid nontraditional engines. The recommended engine for my Pulsar was the Rotax 912. I had no experience with the Rotax before installing it, but the instructions were excellent. The engine was easy to hook up and reliable to fly with.

Two-Strokes. For smaller projects, the world of two-stroke engines has gotten larger and more reliable. Two-stroke engines got a bad rap from being associated with small lawn mowers. We would put the mower in the corner of the shed and then expect it to start in the spring. When it didn’t start, we’d remark about how unreliable it was in the face of getting little to no care or maintenance. The fact is that the aircraft two-strokes do require a little more attention. However, they can be highly reliable if we perform inspections and maintenance.

Plan ahead. Lead times on engines and on engine overhauls are high, and that probably won’t change any time soon. It’s better to get your engine early and put it into proper storage than to be done building and be waiting for your engine. Don’t exchange a shorter lead time for an engine far down on your list. Be patient and you’ll end up happier over the long term.

Automobile engine conversions. These have gotten less risky and more reliable. If you go in this direction, stick with a well-known engine and installation package. Don’t make changes to it unless you are highly experienced. Any changes you make to the package engineering will drive up risk and lower safety.

One of the biggest reasons for building our own airplane is to get exactly what we want. From performance to design, comfort, and ease of maintenance, we are putting together a unique combination of things that reflect our own personalities. Choosing an engine for our airplane is a mosaic of all these factors. Don’t leave logic and risk out of this equation. If you select your engine carefully after advice and research, you’ll be a happy pilot and won’t need to do any second-guessing.

Lisa Turner, EAA Lifetime 509911/Vintage 724296, is a retired avionics manufacturing engineer, an EAA technical counselor/flight advisor, and A&P mechanic. Lisa has authored six books. Dream Take Flight details her Pulsar building and flying adventures. For the Love of an Airplane is the biography of Jerry Stadtmiller, a man who restored more than 100 antique aircraft to flying condition. Learn more at DreamTakeFlight.com. Write Lisa at Lisa@DreamTakeFlight.com.