By John Wyman, EAA 462533; Chapter 266, Montreal

I’ve been thinking about aviation accidents lately, and how it’s often the smaller, overlooked items that can cause the most serious problems. What is truly astounding is how even the most tested and experienced pilots can fall prey to this phenomenon. All it takes is for the holes of the Swiss cheese to line up, and soon enough the error has made it all the way through the block with nothing to slow it down and stop it! (The James Reason Model). We study this at the airline until we can recite the courses from memory, yet it’s still out there, lurking and ready to strike when we least expect it.

This brought to mind how glider pilots ask others around them, when rigging their aircraft, to not interrupt so that they won’t overlook something critical like attaching up control surfaces. Interruptions like these have prompted them to always conduct positive control checks before flights where one person remains at the control surface and the other moves the stick to see if indeed pressure is felt at the other end and vice versa when the stick is pushed or pulled and the control is held in place.

It isn’t just about the direction of travel. This ‘positively’ confirms that the two are attached and there is positive control. I know of one instance where a pilot rigged their glider only to have the control (in this case the elevator) move in the correct direction versus stick input only because of how the elevator push-rod acted on the elevator control arm, applying correct movement without being attached!

When the nose was commanded up (stick back, elevator up) the push rod pushed the elevator up, and when the nose was commanded down (stick forward, elevator down) the weight of the elevator followed the push rod down, falsely convincing the pilot that the control was attached, as observed from the cockpit. Fortunately, it miraculously didn’t result in a crash, but the pilot quickly realized that control was lost when the glider became airborne on the aerotow, with him disconnecting quickly, deploying full flaps, pitching his nose forward (albeit, the control wasn’t connected!) — somehow carrying out a flare to landing with just enough runway remaining with barely any fore and aft control. It was a close shave.

EASA (The European Aviation Authority) issued a Safety Information Bulletin this year on February 25 outlining some examples of recurring incidents that have led to accidents from misaligned pins, safeties, and other rigging basics. It is called “Sailplane Rigging — Procedures, Inspections and Training” Read it here.

I too have been surprised on a few occasions where only on close inspection of my airplanes (prior to flight) did I discover something that looked amok. The latest event happened only a few weeks ago, where, much to my discomfort (and relief), I discovered a cabin heater deflector (a small piece of round aluminum sheet about 4 inches in diameter) that had detached from the backside of the engine firewall in our Cessna 140, lodging itself in behind the left rudder pedal on the passenger side, potentially preventing any left rudder pedal application!

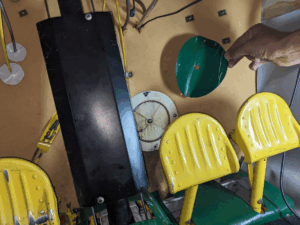

The only reason I discovered it at all was because my head was down in that area working on fixing a leaking brake master cylinder. At one point I looked across at the passenger side and noticed that there was a white outline on the firewall (the surrounding insulation was a different color) of ‘something’ that I hadn’t really noticed before… the cabin heater valve. Looking a bit further I saw that a deflector shield had worked its way loose (two PK screws had backed out) and that the shield (painted the same color as the pedal covers, dark green) had slipped down in behind the left pedal on an angle and seamlessly had blended in with the pedals!

Testing the left pedal to the firewall revealed that there still was full travel albeit it was only there because the shield had fallen slightly to one side, still permitting full deflection. I was only able to catch this hidden mess because when I had been prepping the aircraft for flight the week before, I decided at some point that there were too many things to do and that it might be wise to hold off for another day when there was more time and sunlight to properly look the aircraft over.

Cellphones, cameras, pens, and the multitude of devices that we carry around with us these days can also cause havoc with controls in or around the cockpit. Try to keep it clean and tidy, and remember that if it’s gonna move on its own, it will. I’ve stopped buying the standard black and white gadgets that all companies seem to market. Instead, I now go for BRIGHT stuff that contrasts with the black or dull interiors we see all the time. If it ain’t bright, I’ll make it so with some bright tape or a sticker.

My flight bag even reflects this where something red or green against its interior black lining stands out. Several years ago I had taken a 35-mm camera up in the Pitts (no real floor, just the interior steel tubes and exterior fabric), and after the flight I was at a loss as to what happened to it — only to later see that it had lodged itself in the tail, just to the underside of the elevator bellcrank. Some aerobatics (likely hammerheads) had made it come loose from wherever it was, gradually making its way to the tail. It too was black and in a black case. Sitting there at the lowest part of the fuselage (a darker area) made it a real challenge to spot. Fortunately the tail didn’t have any solid panels down near the tailwheel, and the fabric there was able to give a little bit of way to the camera when the bellcrank touched it. Had it lodged in there in any other position than what I found it in, I would have been a goner.

Once in a while an old dog can be taught a new trick. I recently saw a video where one blogger noted that his flight instructor once told him to do a control check prior to entering the cockpit and another once the engine was running. Why? Because during the first control movement you can listen for any fretting or rubbing noises that just might be an indication that something’s up. You can feel that in the controls. With the engine running you won’t hear or feel that with the vibrations. Another friend added that when he was flying the Grumman Widgeon (an amphibian) this was standard practice. Noises are hard to pick up because the tail is so far back. He went on to add that a post-flight inspection is also just as valuable. Put a note on the dash to remind you to check it out before the next flight if you can’t check it out right away!

Look real-real close next time you fly, and you just may discover some gremlins roaming about!

John Wyman, EAA 462533, Chapter 266 Montreal, is a passionate aviator. When he isn’t in the saddle at the airline, he can be found out at the airfield doing any number of things. He likes to fly gliders, practice aerobatics, write, work on airplanes, and fix stuff.