By Rick Ernst, EAA 418493

This piece originally ran in the December 2025 issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.

I’m a fourth-generation pilot and third-generation A&P mechanic, so there was never a doubt that I would eventually build my own airplane. Sure, I had worked on projects in my restoration shop, but starting my own project from the beginning would be something very different.

Over the years, I have read (eagerly!) many articles that begin like that. But that is not my story.

My 30-year journey to completing a homebuilt airplane was not a direct route, but I suspect it will seem familiar to some. For me, stops in construction were the rule, not the exception. My project and I moved several times over the span of the build. And for many years, my shop was a dark, uninviting garage. But I finished the build, and the result is a terrific Van’s RV-6A.

Possibly the only aspect of my project that took a direct route was my decision to start it. After working my way through the certificates and ratings up to CFI, I knew how to fly but knew little about the airplanes themselves. Like many pilots, all I knew of the engine was what I could see through the oil-filler door. I needed more, and building an airplane was the next “rating” to pursue.

In 1993, I attended a sheet metal workshop given by RV-6A builder John Shoemaker, which gave me the confidence that I could build an airplane. Some stick time in John’s RV made it clear that the -6A was the airplane for me. (Advice to would-be builders: Find your own John Shoemaker or attend an EAA SportAir Workshop. And make sure you’re building an airplane you know you’ll like.)

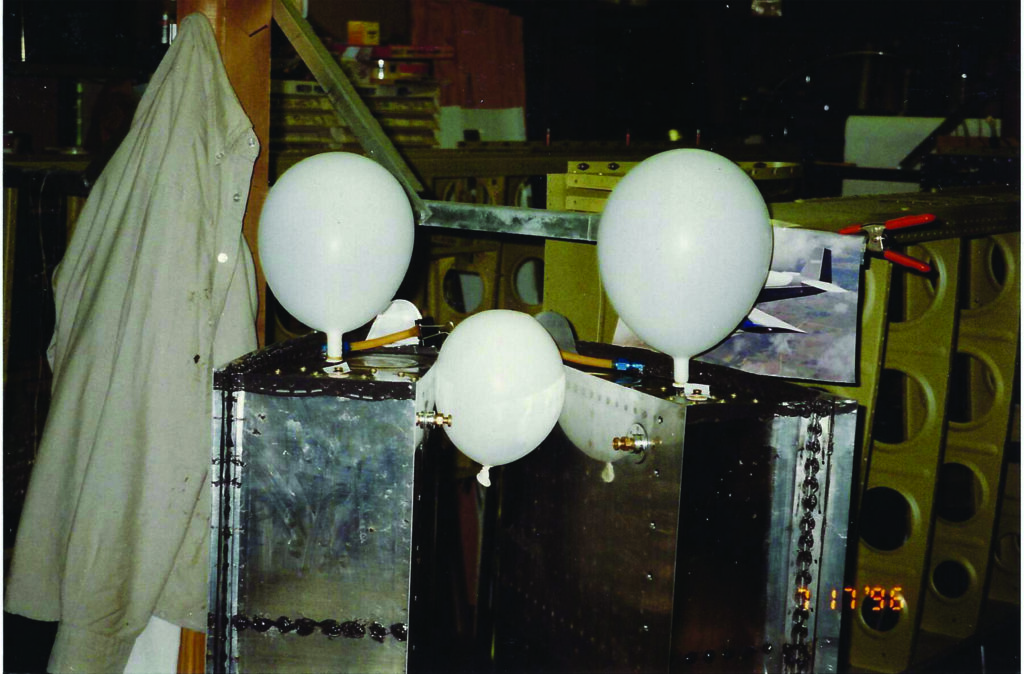

The following year, I moved to Conway, Arkansas, and started my own -6A, with a two-bedroom apartment as my shop. I tried to do the noisiest work on weekends, but still, I can’t imagine what my neighbors thought. Applying corrosion protection in my spare bedroom was probably not the best idea, but I did get my security deposit back. With no air compressor, I could only squeeze rivets, which meant that a lot of the riveting would have to wait. I alternated work from stabilizer to elevators to rudder, back and forth, leaving each assembly unfinished. Such was the start of my nonlinear project trajectory.

By pure chance, I met RV-4 builder Howell Heck. Howell generously provided shop space — and compressed air — so I could finish riveting those tail surfaces, a year after starting them. More importantly, he got me to stop overthinking and to start doing. To the extent that my build was successful (and it was!), I have Howell to thank. (More advice: Find your own Howell Heck; they’re out there, and they would like nothing more than to help you.)

I am happy to have built my airplane from a slow-build kit. Even back in 1995, Van’s offered prebuilt wing spars, but I could not pass up the opportunity to save a few dollars and use what is now among my favorite aircraft tools: the sledgehammer, used to set the large rivets in the spar. The wings were completed, and I started the fuselage by early 1997 — and construction stopped completely for over a year. I changed jobs, changed careers, moved from Conway to Chicago, and married Claudine.

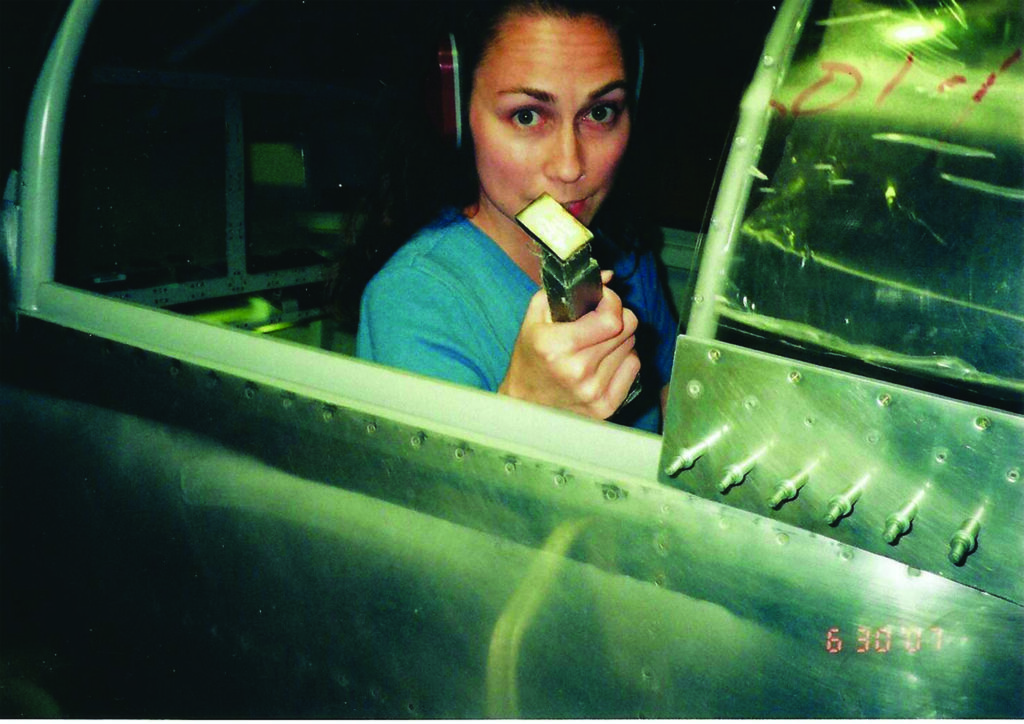

We moved into an apartment that thankfully included a one-car stall in a three-car garage. The garage was convenient, but with no heat, poor lighting, spiderwebs in the rafters, and crumbling brick walls, it felt like a cave. We shared the garage with our upstairs neighbor, but strangely, he never once asked about the airplane. Stranger still was the 55-gallon barrel labeled “Boneless Beef Navels” in his part of the garage. In spite of the surroundings, Claudine was always willing to help. With a bucking bar and hearing protection, she contorted herself into the tail cone and underneath the instrument panel, while with the rivet gun I created the sonic equivalent of hitting a garbage can with a baseball bat. (More advice: Make your shop at least a little comfortable. Remove all meat products from the shop area.)

After 12 years working in the cave-shop, we moved the RV, now with an engine and landing gear, to our new house. My planning was not perfect: I discovered that the horizontal stabilizer on an RV-6A is just a couple inches wider than the garage door opening, but a simple 27-point turn allowed us to extricate it. Surprised neighbors showed up to take pictures, previously unaware of the airplane down the block.

Ironically, in my new, clean shop, progress slowed. I began feeling that because I didn’t have everything I needed to complete any assembly, I couldn’t do anything. Claudine came to the rescue as always, reminding me, “You like the process of building, right? So what if it’s not completed? You still like building.”

Nine years later, we moved the RV to EAA Chapter 461’s hangar at Clow airport (1C5), for final assembly. This time, I discovered that the landing gear on the -6A is just a bit wider than the opening on the trailer I’d rented. With all the help and encouragement I could ask for around me (even if I didn’t always take advantage of it), progress accelerated. With two other RVs under construction in the same hangar, we dubbed the hangar “Airplane Factory 461.”

I finished construction of N921CR on September 27, 2024, 30 years to the day from when construction began. First flight was on April 30, 2025, and flying 1CR was every bit as thrilling as I had hoped it would be back in Conway in 1994. I just completed my task-based Phase I flight testing and am looking forward to a lot more flying. (My last advice: Stick with it. It’s completely worth it.)

Attention — Aircraft Builders and Restorers

We would love to share your story with your fellow EAA members in the pages of EAA Sport Aviation magazine, even if it’s a project that’s been completed for a while. Readers consistently rate the “What Our Members are Building/Restoring” section of the magazine as one of their favorites, so don’t miss the chance to show off your handiwork and inspire your peers to start or complete projects of their own. Learn more ->