By Jessica Schaefer, EAA 1284501

Art by Carissa Photopoulos, Photopoulos Family Photography

It’s almost 11 a.m. on Friday, and the weekend is still not warming up. My phone has been beeping with cold weather alerts, and it’s time to make a call. We’re scheduled to leave at 7 a.m. Saturday and still looking at wind chills of negative 40. Even seasoned winter-lovers know when to call it quits and let the weather win. I text someone else for backup. Delay our start to 9 a.m.? It’s supposed to warm up to negative 20. We agree.

And so, on Saturday morning, with the weather slowly climbing from negative 40 to negative 20, we meet at the airport and set off for a two-and-a-half hour road trip.

We’re eager to get to the warm hangar on the other side, but not because we don’t have that at home. We do. We’ve been working on the restoration of a 1946 Commonwealth Skyranger, a fantastic production aircraft that at one time held some mystical hope of being an “every man” type of transport. With the advent of WWII, the Rearwin Company was forced to stop production and pivot with the nation. They began producing Waco combat gliders, and any bit of material that could be used, was. Unfortunately, that meant the jigs and forms for the Skyranger were scrapped, and when Rearwin sold out to Commonwealth and production was restarted, the first dozen were built by hand. Not so ironically, that’s exactly what we’re left to do today — rebuild jigs based on patterns and old photographs of plans, follow the history, remake things just the way they were.

It’s the perfect project for a group like Wausau’s Learn Build Fly. Built from a wild ask — that the local EAA Chapter 640 finish the late Paul Poberezny’s Mechanix Illustrated Baby Ace replica — and formed off the realization that if you had the people, you could do almost anything. Learn Build Fly has grown into an incredibly active group with two full-sized, heated hangars that are a builder and tinkerer’s dream.

And builders and tinkers noticed. EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame member Forrest Lovley. EAA 19414, donated a project — the Skyranger — to Learn Build Fly in 2019. Slowly, funding was raised and board decisions were made, and work began. In 2023, volunteers at Learn Build Fly had stripped the aluminum off the wings and made the first replacement rib. In 2025, focus returned to the Commonwealth — we repaired and replaced ribs and wing tips and got everything to align well enough. In December, the wings were packed up and sent to Boyceville Air Services for final check, fabric covering, and paint. Meanwhile, we would move on to the fuselage.

I really didn’t want to let those wings go. Despite my attachment to the airplane, it’s not actually mine. I hold no role at Learn Build Fly except for the ever-common shared hat of “volunteer” — an important and honored one, but nonetheless, the wings were leaving and it wasn’t my call.

“But Dave,” I tried, “what if we just go out there?” I’m pretty sure Dave’s funny look was a mix of surety that I had no idea where “there” was, and realization that it didn’t matter.

Dave Conrad, EAA 206314, co-founded LBF with Kurt Mehre, EAA 170963, in 2014 with the goal of continuing to educate young people and anyone else interested in aircraft construction. It was Kurt who had got that original call from Audrey Poberezny, and Kurt who now took lead with me on the Skyranger project. Dave, while busy with the many other demands of the organization which also boasts a computer lab with Autodesk Inventor software, welding, woodworking, composites, and always a few aircraft builds or restorations in process — Dave made the call.

He texted me a few days later. “I talked with Joel Timblin [EAA 688155] about you and some young people visiting the Skyranger wings and helping out. He thought it was a great idea…” Dave forwarded contact info both ways, and by the time I’d gotten Joel’s number in my phone, it was ringing.

He wanted to know how many we’d have along and what I thought about getting in some real hands-on work. “We’ll feed you and put you to work,” he said, with his wife and fellow restorer, Becky, agreeing heartily in the background.

And so, it came to be that on that frigid morning, my economy SUV was full of eager young people, jackets, gloves, and smiles — all of us headed for a day of fabric work.

In its infancy, Learn Build Fly had done fabric covering on the Baby Ace, but that was 2014. Our team for the day included two who weren’t even born then. The rest of us hadn’t joined until much later — myself and my three daughters shortly after our move to Wisconsin in 2022.

By then, LBF was working on its own experimental, a mashup of Wittman Tailwind and Buttercup, working off the Butterburger Clement Mods. Dubbed the Wittman Legacy, the first one off the line won our team a plansbuilt award at AirVenture 2025.

My girls and I had been a part of that project, and done some fabric work — but Hazel, now 9, was only 6, and didn’t remember at all. Even the older youths seemed to have only vague fond memories of the process. With the whole fuselage ahead of us, it was time to get hands-on training.

We are a ragtag, hardy bunch:

Myself, an A&P school dropout who never made it to flight school; Jacob, EAA 1332663, our 19-year-old Ray Aviation scholar who started his own laser engraving business when he was 15; Nathan, EAA 1316884, a 19-year-old student pilot who has fixed the LBF simulators and computers from his dorm at the University of Wisconsin Platteville more times than he should probably count; Derek, EAA 1316886, 19, our second Ray Aviation scholar who worked to build code for LBF’s scrap built tube laser cutter. Lily, EAA 1462246, 16, who surprised her mom a year ago when she hopped off a PB4Y-2 and told the local TV reporter that she was planning to get her pilot certificate so she could help keep vintage aviation alive. (I heard this first on the recorded broadcast, mind you.)

Hazel, EAA 1462248, age 9, who thought at age 7 that she would never be old enough for Young Eagles (it starts at the ripe old age of 8) and took off on her own making friends with pilots in an attempt to gain eight hours of flight time before her 8th birthday. She has over 40 hours, in everything from Bucker to Taylorcraft to Aeroprakt to T-6. Then there’s Carissa, a former Army medic and now photographer; and perhaps the most well behaved of all of us, 9-year-old Everett, EAA 1684952, who lately has been busy perfecting his welding skills while he waits for warm weather to get back to his woodworking business.

We’re a ragtag and admittedly pretty impressive group, but we’re still human, and we can hardly contain our excitement as we burst into Joel and Becky’s hangar off the end of the runway in Boyceville. They’re wearing beanies but to us, it’s delightfully warm. We shred layers and eat lunch together. Soon Pete Hall, EAA Lifetime 1235295, joins us. He’s a builder too, and it turns out, we’ve all got pictures of his airplane. Pete’s Magic Mystery Machine Carbon Cub, he admits sheepishly, was “kinda a crowd favorite.”

The white board behind the lunch table has already gotten hesitant laughs, but Joel reviews with a straight face:

Welcome Learn Build Fly

- Opening Remarks, 60 mins

- Learning Worksheets, 30 pages

- Lecture, 60 mins

* Short 100 question exam with an optional essay.

Go home with lots of knowledge.

There are plenty of mock sighs and giggles. Joel’s straight face was no match — these kids have grown up in airport hangars. They speak sarcasm and think they know pretty well when someone is pulling their leg. Joel grins and flips the board.

Let’s get to work.

He gives us a choice — watching and a bit of hands-on work on our wings, or jump right in with practice on other pieces. It’s unanimous.

We put on invisible gloves, layer up with latex gloves, put on safety glasses, and listen to the briefing. Use your PPE, Joel reminds the youths, “so you can keep doing this.”

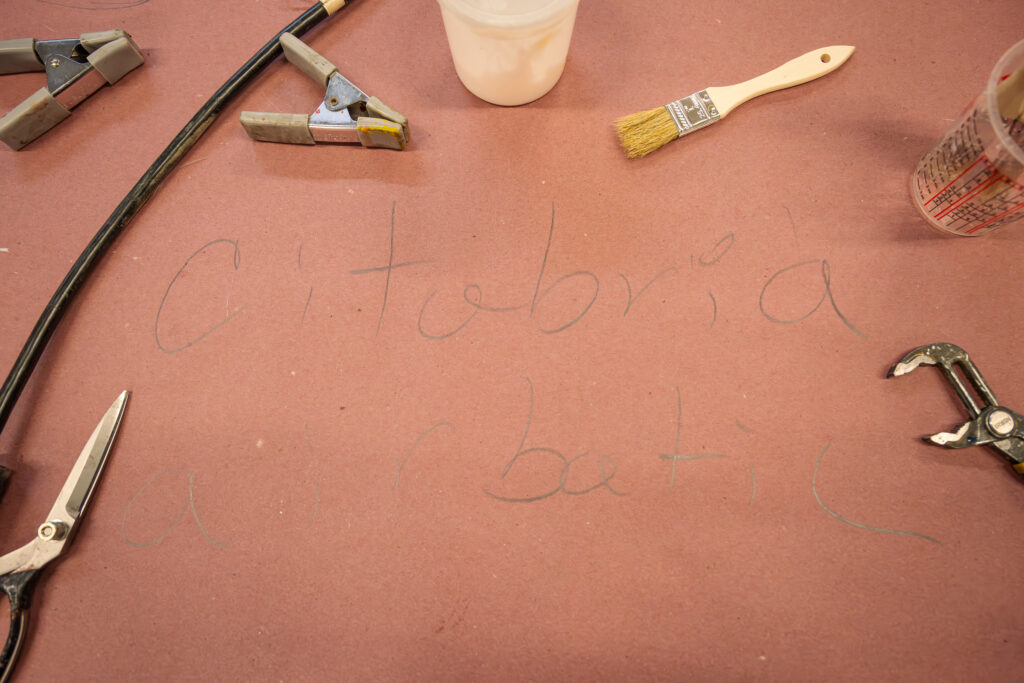

Becky pulls out two Citabria elevator pieces, the bare green coated metal we’re fairly accustomed to seeing. He writes Citabria in big looping letters on the paper covered table. Know what’s special about that name? “Look at it backwards,” he says. Everyone’s heads tilt in unison. Backwards it reads “airbatic,” a clever nod to the aerobatic nature of the Citabria. Joel is full of facts. We love him already. Lily and Hazel look over at me. I know what they want. They want something to fly aerobatics in. A Citabria, Mom, would do just fine.

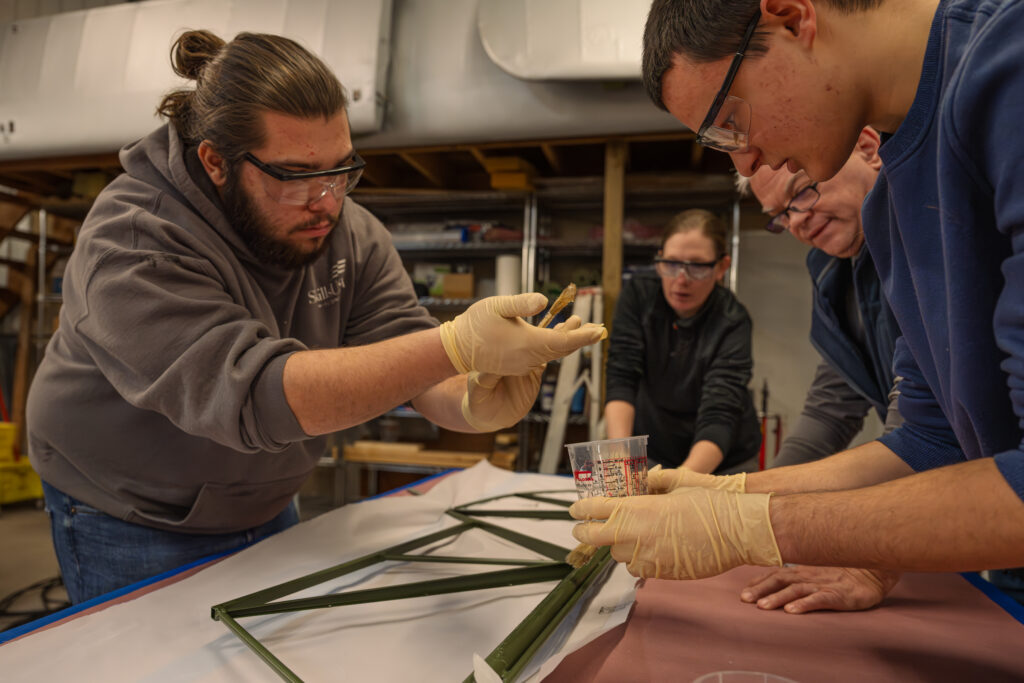

We break into two teams: Joel working Lily and Hazel, Nathan and Everett, who, amusingly, look like miniatures in their matching reds and greys. If you couldn’t picture how kids grow up here, you can’t miss it now. We start by laying out the Poly-Fiber medium weight fabric, talking through the measurements, making those first hesitant cuts. Pete shows our crew how he does it, different from Joel, but it doesn’t matter, he says. Fabric covering is forgiving. You’ll see.

We make our lines and cuts and corners with lots of discussion and precision, intent on getting it just right. Don’t be too fussy, Pete says. You’ll see.

Our perfectly cut corners, it turns out, make it hard to pull the fabric where we want it. You see now, Pete says. Leave it long next time.

Slowly we make the corners, wrapping the fabric around the edges, gluing for a one-inch overlap. We’re meticulous, making sure when the owners look at the finished product, it’ll look beautiful. It feels like a lot of pressure.

Jacob and Derek and I are used to working together. We communicate effortlessly without concerning ourselves with politeness, we duck in and out of layers of arms. There’s a unique vulnerability to working in a close-knit team, and a powerful strength to it. Joel and Becky and Pete keep feeding us bits of knowledge and advice and we soak it all in. We’ll use this again, and we know it.

Irons come out and are set to 250 degrees Fahrenheit — we walk the corner with them, presetting the fabric where we want it, forming the rounded edge. It’s starting to look recognizable now, more than just an awkward crumbled sheet. When everything is glued, Pete teaches us to trim the excess with fresh razor blades. The sharp edge cuts through the fabric easily, but I hesitate, going too slow, and the fabric pulls. I’ll learn this lesson later. When it’s trimmed, we begin to iron it taut, the first pass at 250 degrees Fahrenheit taking out most of the little wrinkles and excess. Pete tells us not to worry about each edge wrinkle — work from one side to the other and it will pull itself tight. “Like a drum head,” I say. “Yes!” Pete says and looks amused. “I have many talents,” I say. I laugh. So does he. We all have stories and one of the best parts of winter work is the time it gives to tell them.

Joel interviews Pete for us, drawing out the highlights of his story for our appreciation. We ask questions about the Magic Mystery Machine, about his time in the service, about his work now. “Do you work here,” the boys ask, with a hint of jealousy. Pete reminds them his real job is with the airlines. “This I do for fun,” he says. They’re getting inspired. That’s the point, isn’t it?

We talk about what airplane people always talk about — airplanes. Hazel’s first ride was backseat in Cessna 172, piloted by Dennis Seitz, EAA 1217538. Jacob’s first was as a Young Eagle in a Cessna 210 with pilot Jan Bublik, EAA 1152848. The first private flight I can remember was a Cessna T-206 in Ecuador. Pete talks about a J-3 Cub.

Lily’s first was a Young Eagles flight in a polished Cessna 170B out of Andover Aeroplex in New Jersey, piloted by Vincent Lalomia, EAA 253985, from EAA Chapter 501. Nathan and Derek were Young Eagles first flights as well, in the famous Ercoupe Scampy piloted by Syd Cohen, EAA Lifetime 98446, at our home field of KAUW Wausau Downtown Airport.

Everett’s first was a Cessna 177 Cardinal piloted by fellow LBF volunteer Tom Wood, EAA 1120954. Everett is overdue for another, he muses. Carissa mentions she’s never been, something we all want to see remedied.

Pete suggests he might give some flights in the Magic Mystery Machine come spring. We try not to look too eager. Joel and Becky up the ante with a hot air balloon. It’s good to dream of warm weather but also, it’s not bad here in the hangar, getting work done. Once the flying starts in force, all the building somehow slows down.

We have to make good use of these bitter cold days. Everett and Hazel are painting their elevator with Consolidated Aircraft Coatings Poly-Brush, the pink tint clearly showing where they’ve missed until all the fabric is neatly soaked. The fabric sealer closes the pores of the bare fabric. It’s also used to attach finishing tapes, and Joel demonstrates that next, helping Hazel measure out one inch on each side of the line marked down the middle of the tubing below. He uses a hot soldering iron to put evenly spaced holes in the fabric for stitching. Then, to our horror, Becky drops a pair of scissors.

Rip goes the fabric. Everyone stops. Joel and Becky, however, are still grinning.

Suddenly it occurs to us that elevator No. 1 is purely a training tool. That accidental mishap was planned. Everett adds another layer of sealer to their mock access panel.

Well, we muse from the other end of the bench, they did go a little faster. Maybe it didn’t turn out quite well enough to keep. Jacob is finishing another round of ironing on our elevator. No. 2, the hard one, the one with the trim tab. This time we’re ironing on 350 degrees Fahrenheit and the fabric pulls taut. We tap gently and share hesitant nods. Did we do okay?

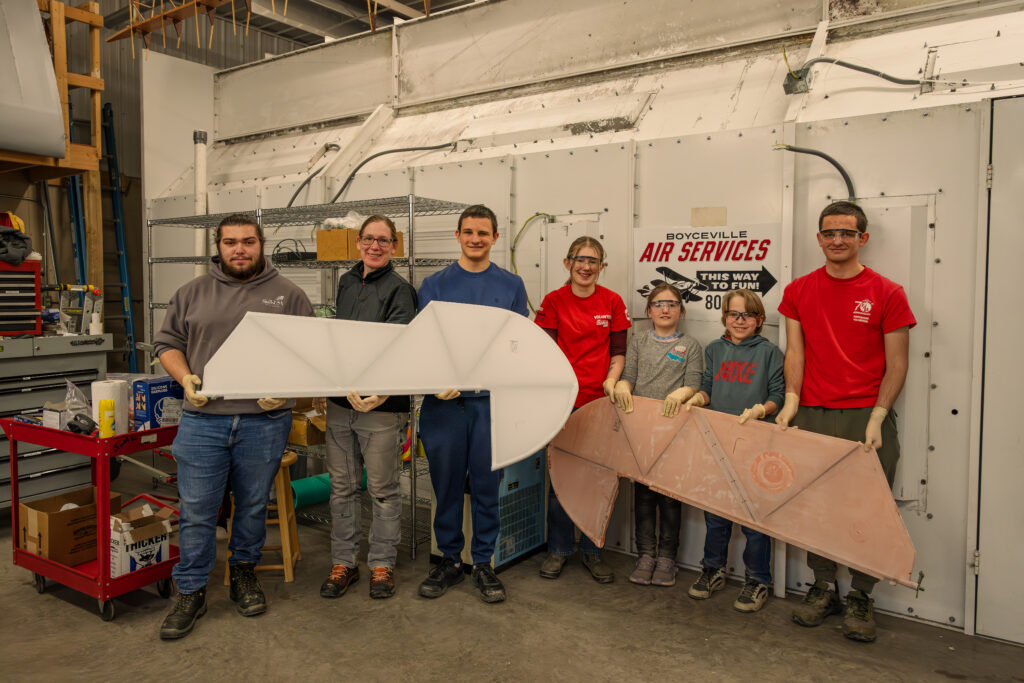

We all pause to take a group picture with the elevators, and then No. 1 gets stripped of the practice skins. As the last of it hits the table in shreds, Joel says, “Oh, maybe I wanted to keep that on there…” There are plenty of laughs. We’d do it again. And we will.

Joel comes over to inspect elevator No. 2. “Okay, you can take it off now,” he says. He looks closer. “Pretty nice,” he adds. For a moment, we wonder if he’s going to change his mind. But with a wave of his hand, our carefully covered elevator is just a practice piece.’

We share a bit of relief that we won’t be rolling under rows of Citabrias at AirVenture 2026, checking to see if that one wrinkle never came out. Joel tells us we’ll see plenty of fabric flaws now that we know what to look for. One elevator done top to bottom and the other bottom to top. Seams with too many wrinkly layers. I grab a fresh razor blade and run it along the tube. Now that I’m not worried about cutting anything, I don’t hesitate. Now my cut is smooth and nearly perfect. Of course. Some lessons are learned best this way.

Best learned from those with decades of experience who put the tools in inexperienced hands and set them to work. Best learned in warm hangars, full of laughter, snacks, and the bones of a dozen airplanes. Best learned together, in person, with a smile and a story.

We’re a ragtag bunch, with different backgrounds and different futures. But on one bitter cold day in Boyceville, Wisconsin, we did what generations of aviators and homebuilders have done — showed up, worked, and learned. With a little more practice, we’ll keep building, one strip of fabric at a time. When you see our Commonwealth Skyranger someday at AirVenture, feel free to roll underneath, and take a close look. I know already that our aircraft’s story will tell not just of its amazing history but also of the futures that it has helped to build. This is the glue and fabric that future generations of aviators are built from: stories and shared experience, one piece at a time.